Investing in drought-tolerant maize is good for Africa

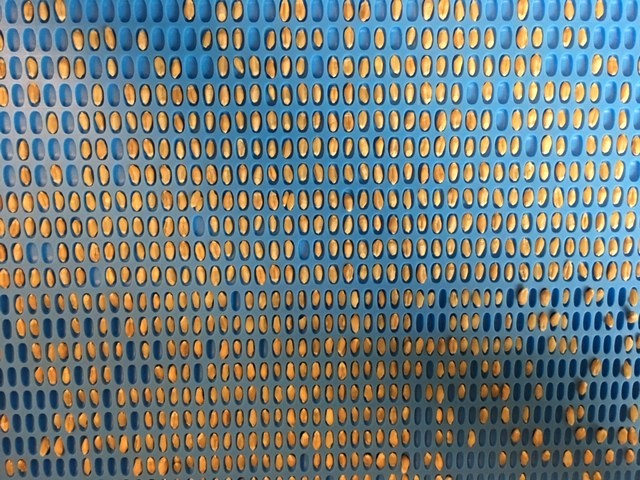

Zambia’s vice-president has recently called to reduce maize dominance and increase crop and diet diversification in his country. The reality is that maize is and will remain a very important food crop for many eastern and southern African countries. Diet preferences and population growth mean that it is imperative to find solutions to increase maize production in these countries, but experts forecast 10 to 30% reduction in maize yields by 2030 in a business-as-usual scenario, with projected temperature increases of up to 2.7 degrees by 2050 and important drought risks.

Knowing the importance of maize for the food security of countries like Zambia, it is crucial to help maize farmers get better and more stable yields under erratic and challenging climate conditions.

To address this, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and its partners have been developing hundreds of new maize varieties with good drought tolerance across sub-Saharan Africa. Stakeholders in the public research and African seed sectors have collaborated through the Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa (DTMA) project and the Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) initiative to develop drought-tolerant seed that also incorporates other qualities, such as nutritional value and disease resistance.

A groundbreaking impact study six years ago demonstrated that drought-tolerant maize significantly reduced poverty and food insecurity, particularly in drought years.

A new study from CIMMYT and the Center for Development Research (ZEF) in the main maize growing areas of Zambia confirms that adopting drought-tolerant maize can increase yields by 38% and reduce the risks of crop failure by 36%.

Over three quarters of the rainfed farmers in the study experienced drought during the survey. These farming families of 6 or 7 people were cultivating 4 hectares of farmland on average, half planted with maize.

Another study on drought-tolerant maize adoption in Uganda estimated also good yield increases and lower crop failure risks by 26 to 35%.

A balancing act between potential gains and climate risks

Drought-tolerant maize has a transformational effect. With maize farming becoming less risky, farmers are willing to invest more in fertilizer and other inputs and plant more maize.

However, taking the decision of adopting new farm technologies in a climate risky environment could be a daunting task. Farmers may potentially gain a lot but, at the same time, they must consider downside risks.

As Gertrude Banda, a lead farmer in eastern Zambia, put it, hybrid seeds have a cost and when you do not know whether rains will be enough “this is a gamble.” In addition to climate uncertainty, farmers worry about many other woes, like putting money aside for urgent healthcare, school fees, or cooking nutritious meals for the family.

Information is power

An additional hurdle to adoption is that farmers may not know all the options available to cope with climate risks. While 77% of Zambia households interviewed said they experienced drought in 2015, only 44% knew about drought-tolerant maize.

This inequal access to knowledge and better seeds, observed also in Uganda, slows adoption of drought-tolerant maize. There, 14% of farmers have adopted drought-tolerant maize varieties. If all farmers were aware of this technology, 8% more farmers would have adopted it.

Because farmers are used to paying for cheap open-pollinated varieties, they are only willing to pay half of the hybrid market price, even though new hybrids are performing very well. Awareness campaigns on the benefits of drought-tolerant maize could boost adoption among farmers.

According to the same study, the potential for scaling drought-tolerant maize could raise up to 47% if drought-tolerant varieties were made available at affordable prices at all agrodealers. Several approaches could be tested to increase access, such as input credit or subsidy schemes.

Read the full articles:

Impacts of drought-tolerant maize varieties on productivity, risk, and resource use: Evidence from Uganda

Productivity and production risk effects of adopting drought-tolerant maize varieties in Zambia

These impact studies were made possible through the support provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), funders of the Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) initiative.