First drought tolerant and insect resistant “stacked” transgenic maize harvested in Kenya

NAIROBI, Kenya (CIMMYT) – Life has become more difficult in Kenya for the intrepid stem borer. For the first time, transgenic maize hybrids that combine insect resistance and drought tolerance have been harvested from confined field trials, as part of a public-private partnership to combat the insect, which costs Kenya $90 million dollars in maize crop losses a year.

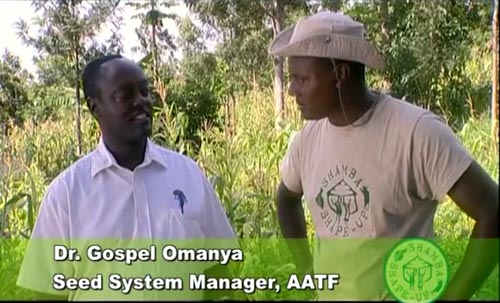

Conducted at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) centers in Kitale and Kiboko in April and May, the experiments were managed by the Water Efficient Maize for Africa (WEMA) project, a collaboration led by the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF). The test crop successfully weathered intense, researcher-controlled infestations of two highly-aggressive Kenyan insect pests— the spotted stem borer and African stem borer.

The maize is referred to as “stacked” because it carries more than one inserted gene for resilience; in this case, genes from the common soil microbe Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) that confers resistance to certain species of stem borer, and another from Bacillus subtilis that enhances drought tolerance.

First time maize resists two-pest attack

WEMA partners from KALRO, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), U.S. seeds company Monsanto and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF) hope that, given the successful results of this experiment, they will soon be able to test the new maize in national trials.

“This is the first planting season of the stacked materials and, from the initial data, there was a clear difference between the plants containing the stem borer resistance traits and the conventional commercial maize grown for comparison, which showed a lot of damage,” said Murenga Mwimali, WEMA coordinator at KALRO.

The maize in the Kiboko experiment was infested with the spotted stem borer (Chilo partellus, by its scientific name), a pest found mostly in the lowlands. At Kitale, the scientists besieged the crops with the African stem borer (Busseola fusca), the predominant maize pest in the highlands. This was the first time that Bt maize had been tested in the field against Busseola fusca, according to Stephen Mugo, regional representative for CIMMYT in Africa and leader of the center’s WEMA team.

“From our observations, this is the first time that stacked Bt genes provided control for both Chilo partellus and Busseola fusca in maize,” Mugo said, adding that stem borers annually chew their way through 13.5 percent of Kenya’s maize, representing a loss of 0.4 million tons of grain.

“Losses can reach 80 percent in drought years, when maize stands are weakened from a lack of water and insect infestation,” he explained. Although the impact of the stem borer in the field often goes unnoticed because the insects sometimes destroy the plant from the root, the loss is significant for a country that depends on maize for food.

The new maize was developed using lines from Monsanto and CIMMYT-led conventional breeding for drought tolerance.

Seeking approval for widespread testing and use

Trial harvesting took place under close supervision by inspectors from the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Services (KEPHIS) and the National Biosafety Authority (NBA), strictly in line with regulatory requirements for handling genetically modified crops in Kenya.

The NBA has given partial approval to KALRO and AATF for open cultivation of the stacked transgenic hybrid maize. Once full approval is given, the varieties can be grown in non-restricted field conditions like any other variety and the Bt maize can be tested in the official national performance trials organized by KEPHIS to test and certify varieties for eventual use by farmers.

“The data we are generating in this trial will support further applications for transgenic work in Kenya, particularly for open cultivation,” Mwimali said.