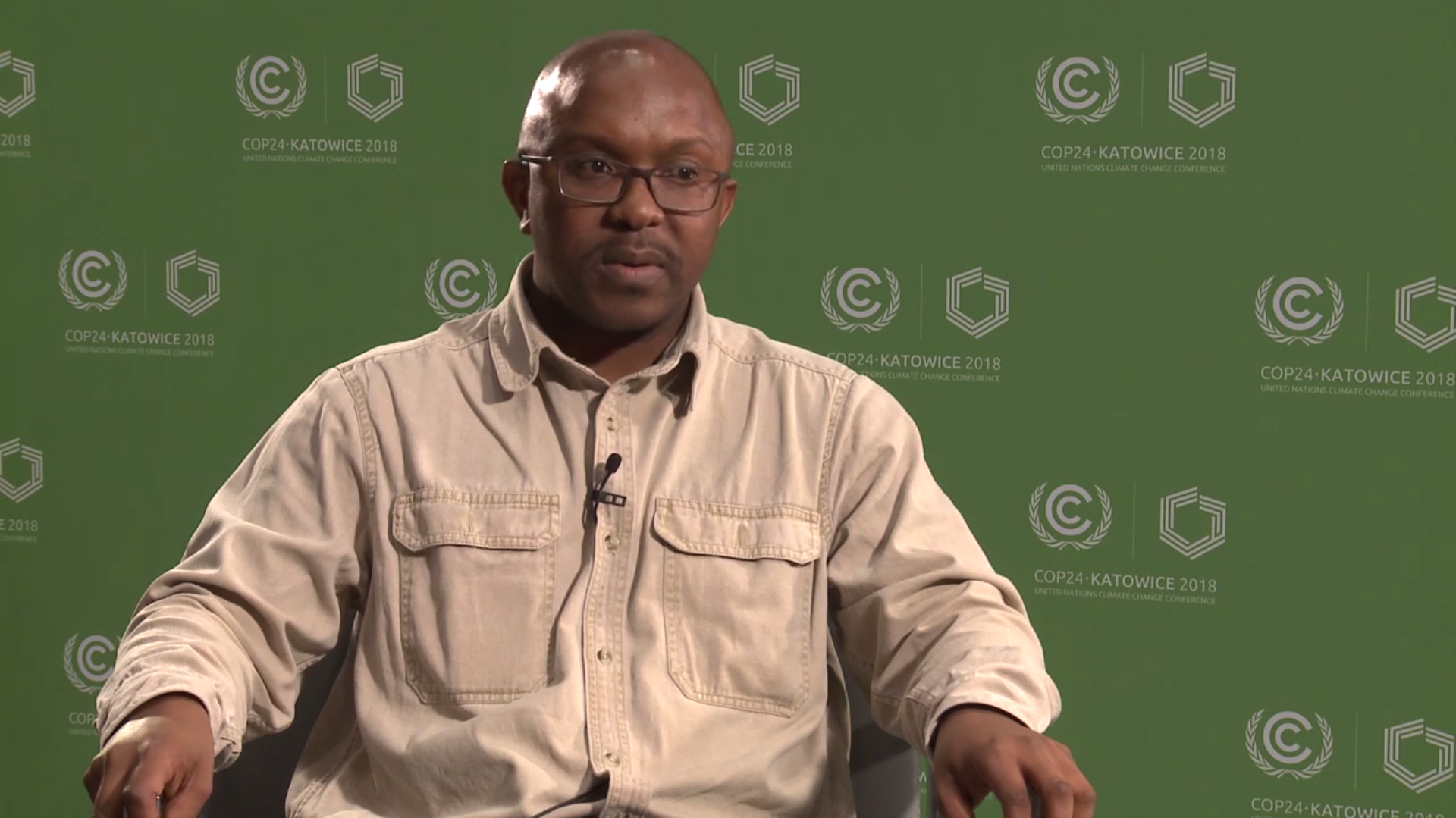

Breaking Ground: Tek Sapkota finds ways to reduce emissions from agriculture without compromising food security

As the world population increases, so does the need for food. “We need to produce more to feed increasing populations and meet dietary demands,” says Tek Sapkota, agricultural systems and climate change scientist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). In the case of agriculture, the area of land under cultivation is limited, so increased food production has to come through intensification, Sapkota explains. “Intensification means that you may be emitting more greenhouse gases if you’re applying more inputs, so we need to find a way to sustainable intensification: increase the resilience of production systems, but at the same time decrease greenhouse gas emissions, at least emission intensity.”

Sapkota is involved in a number of global climate change science and policy forums. He represents CIMMYT in India’s GHG platform, a multi-institution platform that regularly prepares greenhouse gas emission estimates at the national and state levels and undertakes relevant policy analyses. Nominated by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) and his country, Nepal, he is one of the lead authors of the “special report on climate change and land” of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

He coordinates climate change mitigation work at CIMMYT. “I am mainly involved in quantification of greenhouse gas emissions and the environmental footprint from agricultural production systems, exploring mitigation options and quantifying their potential at different scales in different regions,” Sapkota says. In addition, he explores low-carbon development activities and the synergies between food production, adaptation and mitigation work within the different components of CIMMYT’s projects.

Agriculture is both a victim of as well as a contributor to climate change, Sapkota explains. “Climate change affects all aspects of food production, because of changes in temperature, changes in water availability, CO2 concentrations, etc.,” he says. “The other side of the coin is that agriculture in general is responsible for about 25 to 32 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions.”

Measuring emissions and examining mitigation options

A big part of Sapkota’s work is to find ways to mitigate the effects of climate change and the emissions from the agricultural sector. There are three types of mitigation measures, he explains. First, on the supply side, agriculture can “increase efficiency of the inputs used in any production practice.” Second, there’s mitigation from the demand side, “by changing the diet, eating less meat, for example.” Third, by reducing food loss and waste: “About 20 percent of the total food produced for human consumption is being lost, either before harvest or during harvest, transport, processing or during consumption.”

Sapkota and his team analyze different mitigation options, their potential and their associated costs. To that purpose, they have developed methodologies to quantify and estimate greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural products and systems, using field measurement techniques, models and extrapolation.

“You can quantify the emission savings a country can have by following a particular practice” and “help countries to identify the mitigation practices in agriculture that can contribute to their commitments under the Paris climate agreement.”

Their analysis looks at the biophysical mitigation potential of different practices, their national-level mitigation potential, their economic feasibility and scalability, and the country’s governance index and readiness for finance — while considering national food security, economic development and environmental sustainability goals.

Recently, Sapkota and his colleagues completed a study quantifying emissions from the agricultural sector in India and identifying the best mitigation options.

This type of research has a global impact. Since agriculture is a contributor to climate change “better management of agricultural systems can contribute to reducing climate change in the future,” Sapkota says. Being an important sector of the economy, “agriculture should contribute its share.”

Impact on farmers

Sapkota’s research is also helping farmers today. Inefficient use of products and inputs is not only responsible for higher greenhouse gas emissions, but it also costs farmers more. “For example, if farmers in the Indo-Gangetic Plain of India are applying 250 to 300 kg of nitrogen per hectare to produce wheat or rice, by following precision nutrient management technologies they can get similar yield by applying less nitrogen, let’s say 150 kg.” As farmers cut production costs without compromising yield, “their net revenue from their products will be increased.”

Farmers may also get immediate benefits from government policies based on the best mitigation options. “Governments can bring appropriate policy to incentivize farmers who are following those kinds of low-emission technologies, for example.”

Farmers could also get rewarded through payments for ecosystem services or for their contribution to carbon credits.

Sapkota is happy that his work is beneficial to farmers. He was born in a small village in the district of Kaski, in the mid-hills of Nepal, and agriculture was his family’s main livelihood. “I really enjoy working with farmers,” he says. “The most fascinating part of my work is going to the field: talking to farmers, listening to them, learning what kind of farming solutions they’re looking for, and so on. This helps refine our research questions to make them more strategic, because the way farmers look at a problem is sometimes entirely different from the way we look at it.”

When he was in Himalaya Secondary School, he studied agriculture as a vocational subject. “I was interested because we were doing farming at home.” This vocation got cemented in university, in the 1990s. When he heard about the agricultural industry and the future opportunities, he decided to pursue a career in science and focus on agriculture. He got his bachelor’s and master’s degree of science in agriculture from the Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science (IAAS), Tribhuvan University, in Nepal.

A global path

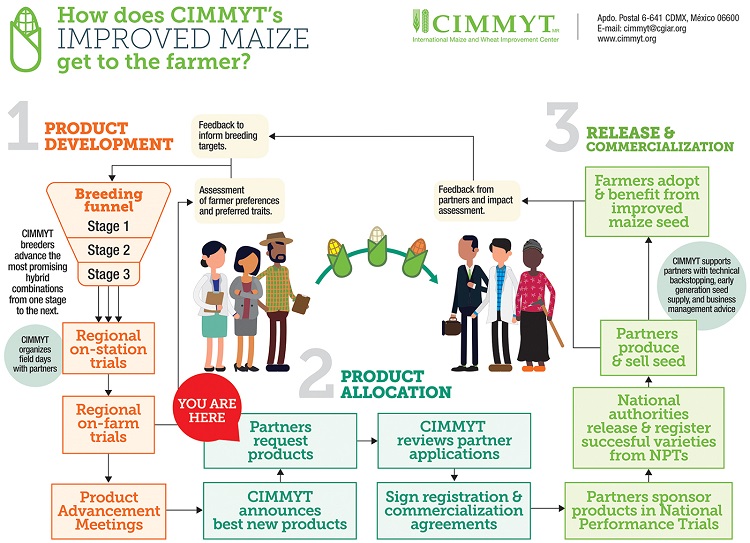

He first heard about CIMMYT when he was doing his master’s. “CIMMYT was doing research in maize- and wheat-based plots and systems in Nepal. A few of my friends were also doing their master theses with the financial support of CIMMYT.” After his master’s, he joined an organization called Local Initiatives for Biodiversity, Research and Development (LI-BIRD) which was collaborating with CIMMYT on a maize research program.

Sapkota got a PhD in Agriculture, Environment and Landscapes from the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies in Italy, including research in Aarhus University, Denmark.

After defending his thesis, in 2012, he was working on greenhouse gas measurement in the University of Manitoba, Canada, when he saw an opening at CIMMYT. He joined the organization as a post-doctoral fellow and has been a scientist since 2017. Sapkota considers himself a team player and enjoys working with people from different cultures.

His global experience has enriched his personal perspective and his research work. Through time, he has been able to see the evolution of agriculture and the “dramatic changes” in the way agriculture is practiced in least developed countries like Nepal. “When I was a kid agriculture was more manual … but now, a lot of technologies have been developed and farmers can use them to increase the efficiency of farming”.

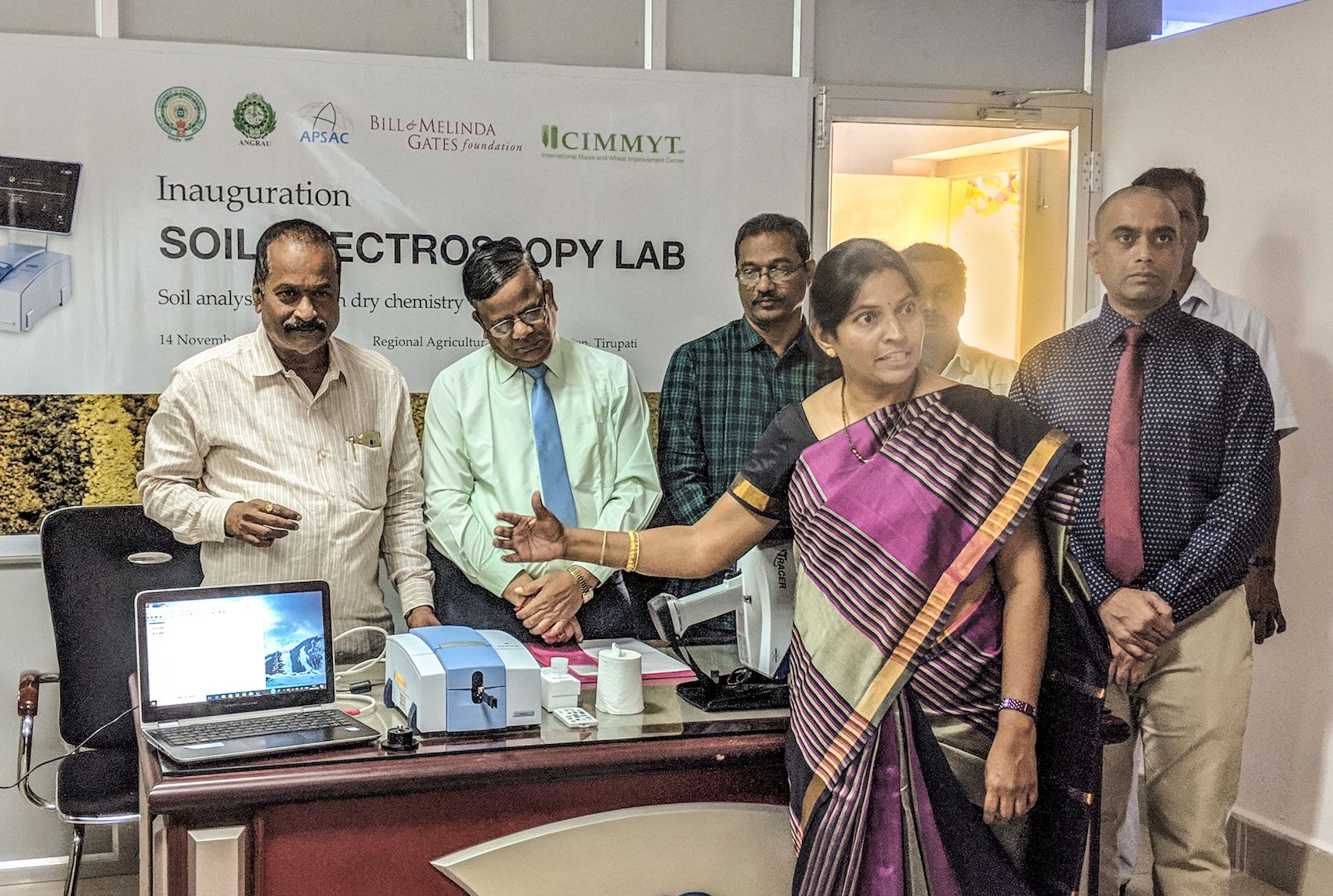

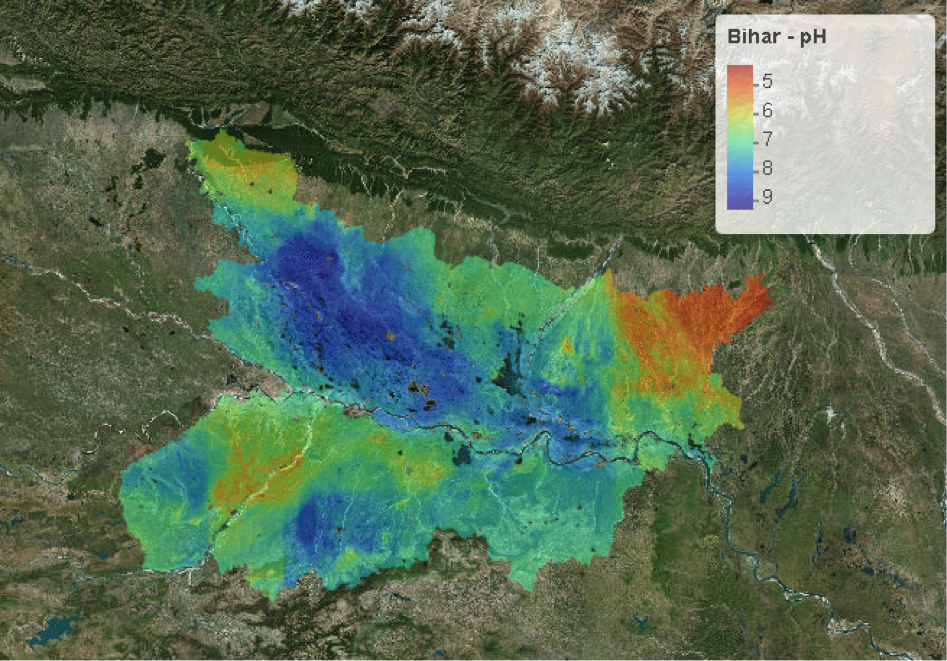

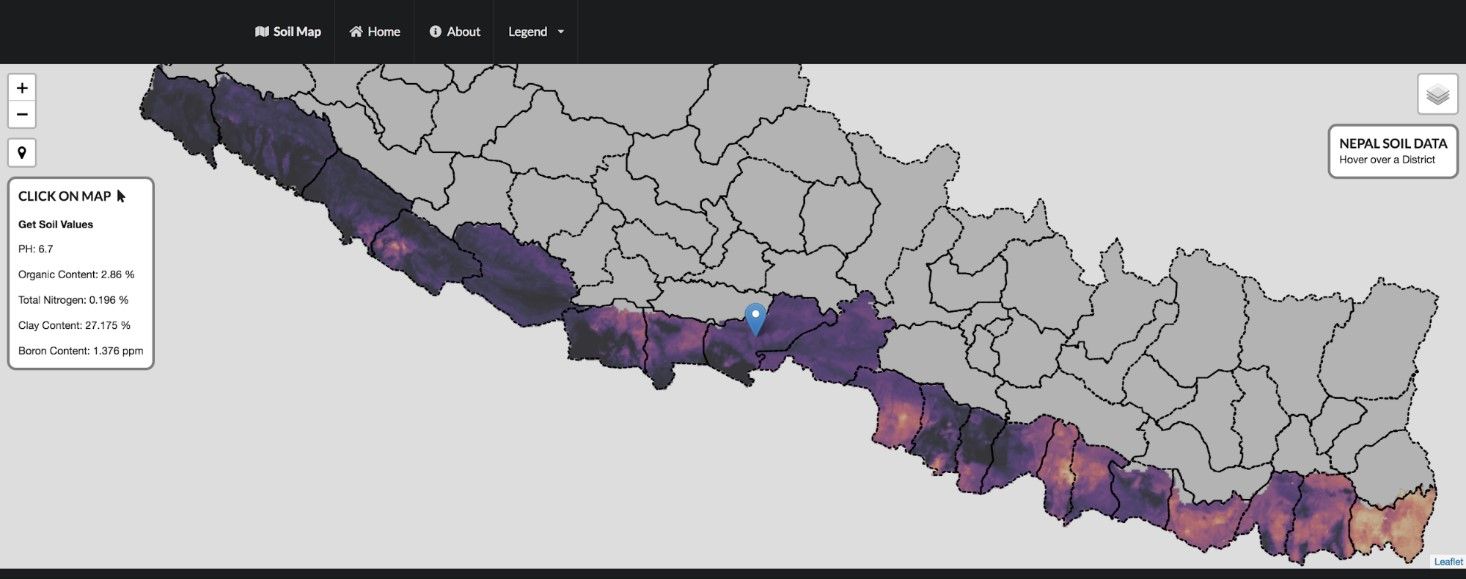

KATHMANDU, Nepal (CIMMYT) — The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is working with Nepal’s Soil Management Directorate and the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) to aggregate historic soil data and, for the first time in the country, produce

KATHMANDU, Nepal (CIMMYT) — The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is working with Nepal’s Soil Management Directorate and the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) to aggregate historic soil data and, for the first time in the country, produce