The tremendous diversity of crops in Pakistan has been documented in a new publication that will foster more effective and targeted policies for national agriculture.

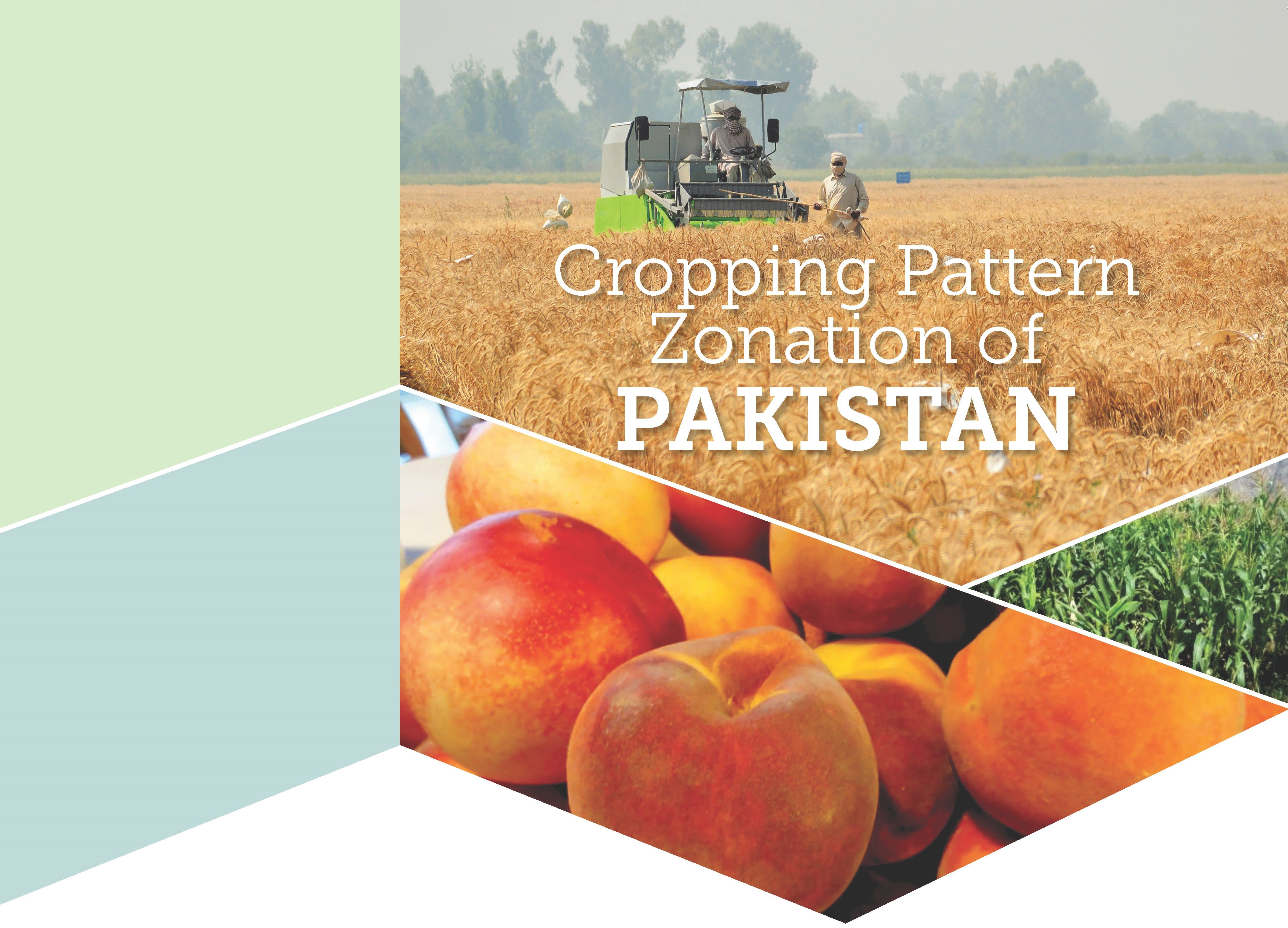

Using official records and geospatial modeling to describe the location, extent, and management of 25 major and minor crops grown in 144 districts of Pakistan, the publication “Cropping Pattern Zonation of Pakistan” offers an invaluable tool for resource planning and policymaking to address opportunities, challenges and risks for farm productivity and profitability, according to Muhammad Imtiaz, crop scientist and country representative in Pakistan for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

“With rising temperatures, more erratic rainfall and frequent weather extremes, cropping pattern decisions are of the utmost importance for risk mitigation and adaptation,” said Imtiaz, a co-author of the new publication.

Featuring full-color maps for Pakistan’s two main agricultural seasons, based on area sown to individual crops, the publication was put together by CIMMYT and the Climate, Energy and Water Research Institute (CEWRI) of the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC), with technical and financial support from the Agricultural Innovation Program (AIP) for Pakistan, which is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

Pakistan’s main crops–wheat, rice, cotton and sugarcane—account for nearly three-quarters of national crop production. Various food and non-food crops are grown in “Rabi,” the dry winter season, October-March, and “Kharif,” the summer season characterized by high temperatures and monsoon rains.

Typically, more than one crop is grown in succession on a single field each year; however, despite its intensity, farming in Pakistan is largely traditional or subsistence agriculture dominated by the food grains, according to Ms. Rozina Naz, Principal Scientific Officer, CEWRI-PARC.

“Farmers face increasing aridity and unpredictable weather conditions and energy shortage challenges that impact on their decisions regarding the type and extent of crops to grow,” said the scientist, who is involved in executing the whole study. “Crop pattern zoning is a pre-requisite for the best use of land, water and capital resources.”

The study used 5 years (2013-14 to 2017-18) of data from the Department of Agricultural Statistics, Economics Wing, Ministry of National Food Security and Research, Islamabad. “We greatly appreciate the contributions of scientists and technical experts of Crop Science Institute (CSI) and CIMMYT,” Imtiaz added.

View or download the publication:

Cropping Pattern Zonation of Pakistan. Climate, Energy and Water Research Institute, National Agricultural Research Centre, Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center. 2020. CDMX: CEWRI, PARC, and CIMMYT.

See more recent publications from CIMMYT researchers:

1. Plant community strategies responses to recent eruptions of Popocatépetl volcano, Mexico. 2019. Barba‐Escoto, L., Ponce-Mendoza, A., García-Romero, A., Calvillo-Medina, R.P. In: Journal of Vegetation Science v. 30, no. 2, pag. 375-385.

2. New QTL for resistance to Puccinia polysora Underw in maize. 2019. Ce Deng, Huimin Li, Zhimin Li, Zhiqiang Tian, Jiafa Chen, Gengshen Chen, Zhang, X, Junqiang Ding, Yuxiao Chang In: Journal of Applied Genetics v. 60, no. 2, pag. 147-150.

3. Hybrid wheat: past, present and future. 2019. Pushpendra Kumar Gupta, Balyan, H.S., Vijay Gahlaut, Pal, B., Basnet, B.R., Joshi, A.K. In: Theoretical and Applied Genetics v. 132, no. 9, pag. 2463-2483.

4. Influence of tillage, fertiliser regime and weeding frequency on germinable weed seed bank in a subhumid environment in Zimbabwe. 2019. Mashavakure, N., Mashingaidze, A.B., Musundire, R., Gandiwa, E., Thierfelder, C., Muposhi, V.K., Svotwa, E.In: South African Journal of Plant and Soil v. 36, no. 5, pag. 319-327.

5. Identification and mapping of two adult plant leaf rust resistance genes in durum. 2019. Caixia Lan, Zhikang Li, Herrera-Foessel, S., Huerta-Espino, J., Basnet, B.R., In: Molecular Breeding v. 39, no. 8, art. 118.

6. Genetic mapping reveals large-effect QTL for anther extrusion in CIMMYT spring wheat. 2019. Muqaddasi, Q.H., Reif, J.C., Roder, M.S., Basnet, B.R., Dreisigacker, S. In: Agronomy v. 9 no. 7, art. 407.

7. Growth analysis of brachiariagrasses and ‘tifton 85’ bermudagrass as affected by harvest interval. 2019. Silva, V. J. da., Faria, A.F.G., Pequeno, D.N.L., Silva, L.S., Sollenberger, L.E., Pedreira, C. G. S. In: Crop Science v. 59, no. 4, pag. 1808-1814.

8. Simultaneous biofortification of wheat with zinc, iodine, selenium, and iron through foliar treatment of a micronutrient cocktail in six countries. 2019. Chunqin Zou, Yunfei Du, Rashid, A., Ram, H., Savasli, E., Pieterse, P.J., Ortiz-Monasterio, I., Yazici, A., Kaur, C., Mahmood, K., Singh, S., Le Roux, M.R., Kuang, W., Onder, O., Kalayci, M., Cakmak, I. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry v. 67, no. 29, pag. 8096-8106.

9. Economic impact of maize stem borer (Chilo partellus) attack on livelihood of maize farmers in Pakistan. 2019. Ali, A., Issa, A.B. In: Asian Journal of Agriculture and Biology v. 7, no. 2, pag. 311-319.

10. How much does climate change add to the challenge of feeding the planet this century?. 2019. Aggarwal, P.K., Vyas, S., Thornton, P.K., Campbell, B.M. In: Environmental Research Letters v. 14 no. 4, art. 043001.

11. A breeding strategy targeting the secondary gene pool of bread wheat: introgression from a synthetic hexaploid wheat. 2019. Ming Hao, Lianquan Zhang, Laibin Zhao, Shoufen Dai, Aili Li, Wuyun Yang, Die Xie, Qingcheng Li, Shunzong Ning, Zehong Yan, Bihua Wu, Xiujin Lan, Zhongwei Yuan, Lin Huang, Jirui Wang, Ke Zheng, Wenshuai Chen, Ma Yu, Xuejiao Chen, Mengping Chen, Yuming Wei, Huaigang Zhang, Kishii, M, Hawkesford, M.J, Long Mao, Youliang Zheng, Dengcai Liu In: Theoretical and Applied Genetics v. 132, no. 8, pag. 2285-2294.

12. Sexual reproduction of Zymoseptoria tritici on durum wheat in Tunisia revealed by presence of airborne inoculum, fruiting bodies and high levels of genetic diversity. 2019. Hassine, M., Siah, A., Hellin, P., Cadalen, T., Halama, P., Hilbert, J.L., Hamada, W., Baraket, M., Yahyaoui, A.H., Legreve, A., Duvivier, M. In: Fungal Biology v. 123, no. 10, pag. 763-772.

13. Influence of variety and nitrogen fertilizer on productivity and trait association of malting barley. 2019. Kassie, M., Fantaye, K. T. In: Journal of Plant Nutrition v. 42, no. 10, pag. 1254-1267.

14. A robust Bayesian genome-based median regression model. 2019. Montesinos-Lopez, A., Montesinos-Lopez, O.A., Villa-Diharce, E.R., Gianola, D., Crossa, J. In: Theoretical and Applied Genetics v. 132, no. 5, pag. 1587-1606.

15. High-throughput phenotyping platforms enhance genomic selection for wheat grain yield across populations and cycles in early stage. 2019. Jin Sun, Poland, J.A., Mondal, S., Crossa, J., Juliana, P., Singh, R.P., Rutkoski, J., Jannink, J.L., Crespo-Herrera, L.A., Velu, G., Huerta-Espino, J., Sorrells, M.E. In: Theoretical and Applied Genetics v. 132, no. 6, pag. 1705-1720.

16. Resequencing of 429 chickpea accessions from 45 countries provides insights into genome diversity, domestication and agronomic traits. 2019. Varshney, R.K., Thudi, M., Roorkiwal, M., Weiming He, Upadhyaya, H., Wei Yang, Bajaj, P., Cubry, P., Abhishek Rathore, Jianbo Jian, Doddamani, D., Khan, A.W., Vanika Garg, Annapurna Chitikineni, Dawen Xu, Pooran M. Gaur, Singh, N.P., Chaturvedi, S.K., Nadigatla, G.V.P.R., Krishnamurthy, L., Dixit, G.P., Fikre, A., Kimurto, P.K., Sreeman, S.M., Chellapilla Bharadwaj, Shailesh Tripathi, Jun Wang, Suk-Ha Lee, Edwards, D., Kavi Kishor Bilhan Polavarapu, Penmetsa, R.V., Crossa, J., Nguyen, H.T., Siddique, K.H.M., Colmer, T.D., Sutton, T., Von Wettberg, E., Vigouroux, Y., Xun Xu, Xin Liu In: Nature Genetics v. 51, pag. 857-864.

17. Farm typology analysis and technology assessment: an application in an arid region of South Asia. 2019. Shalander Kumar, Craufurd, P., Amare Haileslassie, Ramilan, T., Abhishek Rathore, Whitbread, A. In: Land Use Policy v. 88, art. 104149.

18. MARPLE, a point-of-care, strain-level disease diagnostics and surveillance tool for complex fungal pathogens. 2019. Radhakrishnan, G.V., Cook, N.M., Bueno-Sancho, V., Lewis, C.M., Persoons, A., Debebe, A., Heaton, M., Davey, P.E., Abeyo Bekele Geleta, Alemayehu, Y., Badebo, A., Barnett, M., Bryant, R., Chatelain, J., Xianming Chen, Suomeng Dong, Henriksson, T., Holdgate, S., Justesen, A.F., Kalous, J., Zhensheng Kang, Laczny, S., Legoff, J.P., Lesch, D., Richards, T., Randhawa, H. S., Thach, T., Meinan Wang, Hovmoller, M.S., Hodson, D.P., Saunders, D.G.O. In: BMC Biology v. 17, no. 1, art. 65.

19. Genome-wide association study for multiple biotic stress resistance in synthetic hexaploid wheat. 2019. Bhatta, M.R., Morgounov, A.I., Belamkar, V., Wegulo, S.N., Dababat, A.A., Erginbas-Orakci, G., Moustapha El Bouhssini, Gautam, P., Poland, J.A., Akci, N., Demir, L., Wanyera, R., Baenziger, P.S. In: International Journal of Molecular Sciences v. 20, no. 15, art. 3667.

20. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of synthetic and bread wheat accessions in Western Siberia. 2019. Bhatta, M.R., Shamanin, V., Shepelev, S.S., Baenziger, P.S., Pozherukova, V.E., Pototskaya, I.V., Morgounov, A.I. In: Journal of Applied Genetics v. 60, no. 3-4, pag. 283-289.

21. Identifying loci with breeding potential across temperate and tropical adaptation via EigenGWAS and EnvGWAS. 2019. Jing Li, Gou-Bo Chen, Rasheed, A., Delin Li, Sonder, K., Zavala Espinosa, C., Jiankang Wang, Costich, D.E., Schnable, P.S., Hearne, S., Huihui Li In: Molecular Ecology v. 28, no. 15, pag. 3544-3560.

22. Impacts of drought-tolerant maize varieties on productivity, risk, and resource use: evidence from Uganda. 2019. Simtowe, F.P., Amondo, E., Marenya, P. P., Rahut, D.B., Sonder, K., Erenstein, O. In: Land Use Policy v. 88, art. 104091.

23. Do market shocks generate gender-differentiated impacts?: policy implications from a quasi-natural experiment in Bangladesh. 2019. Mottaleb, K.A., Rahut, D.B., Erenstein, O. In: Women’s Studies International Forum v. 76, art. 102272.

24. Gender differences in the adoption of agricultural technology: the case of improved maize varieties in southern Ethiopia. 2019. Gebre, G.G., Hiroshi Isoda, Rahut, D.B., Yuichiro Amekawa, Hisako Nomura In: Women’s Studies International Forum v. 76, art. 102264.

25. Tracking the adoption of bread wheat varieties in Afghanistan using DNA fingerprinting. 2019. Dreisigacker, S., Sharma, R.K., Huttner, E., Karimov, A. A., Obaidi, M.Q., Singh, P.K., Sansaloni, C.P., Shrestha, R., Sonder, K., Braun, H.J. In: BMC Genomics v. 20, no. 1, art. 660.

A new testing and learning platform for digital trust and transparency technologies — such as blockchain — in

A new testing and learning platform for digital trust and transparency technologies — such as blockchain — in