Floods highlight importance of food security

The floods in the southern parts of China have triggered fresh concerns about whether the country will face a food shortage and nutrition crisis.

Read more here.

The floods in the southern parts of China have triggered fresh concerns about whether the country will face a food shortage and nutrition crisis.

Read more here.

Seed companies play a crucial role in delivering improved seed varieties to smallholder farmers. Masindi Seed Company Limited, located in Uganda’s mid-western region, is one such enterprise.

It traces its beginnings back to the Masindi District Farmers Association (MADFA) more than a decade ago. At the time, the association, which was comprised of about 9,000 farmers, was organized into a seed out-grower scheme of the then government-led Uganda Seed Project.

While its members were well trained, operated professionally and did their out-grower work diligently, the association faced one major challenge that almost broke it up: the ‘certified’ seed they bought from some seed firms could not germinate.

“At the time that we were operating solely as a farmers’ association, we did our best to grow maize seed for various seed companies who would then go on to produce and supply certified seed,” said Eugene Lusige, Masindi Seed general manager. “But we soon realized that a lot of the certified seed that we bought was of very poor quality due to their inability to germinate or because of low germination rates. This caused our farmers huge losses. We instead took this situation as a blessing in disguise, venturing into the certified seed production business based on our experience.”

Such turn of events meant the association had to not only produce the right seed, at the right price, at the right time and with the attributes their farmers desired, but also had to provide an opportunity to generate income for its members. By establishing Masindi Seed Company in 2009, the association members fulfilled their dream and ended up killing several birds with one stone by addressing multiple seed production challenges.

Over the past few decades, the liberalization of the Ugandan seed industry has seen it morph from government control, largely with the support of public sector research institutions, to increased private sector participation. This saw a resurgence in local and foreign-based seed firms involved in seed production, processing and marketing, which significantly contributed to increased delivery of certified seed to farming communities.

Reliable and beneficial partnerships

As one of the enterprises operating in the formal seed market, Masindi Seed has grown from strength to strength over the years, working closely with the National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI) of the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO) in Uganda. The Longe 5D, an open pollinated variety (OPV) — an improved version of the Longe 5 — was the first certified seed that ushered them into the seed production and marketing landscape in 2009. The company accessed hybrids and parental materials from NARO, which works very closely with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) to obtain improved stress tolerant maize.

“Besides the parental materials we receive from CIMMYT through NARO, we are trained on best practices in quality seed production, and receive materials and financial support for some of our operations,” Lusige said.

In the first year, the company produced about 120-150 tons of the Longe 5D variety, which has remained their flagship product over the past decade. Currently, the variety has up to 65 % share of the company’s annual seed production capacity, which stands at about 1,200 tons. The annual capacity is poised to reach 2,400 by 2025 due to growing demand from farmers. The first stress tolerant hybrid, UH5053, was introduced in 2013 and two more hybrids have since gone into commercial production.

“The hybrids have much higher yield than the OPVs and other varieties in the market in this region. They are stress tolerant and some are early maturing,” Lusige said “But, the advantage with the Longe 5D is that it is much cheaper, with a seed packet going for less than its hybrid equivalent. So, it is best suited for the resource-constrained farmers who may not have the funds to buy artificial fertilizer. However, under normal farmer conditions, it yields between 1.5-1.8 tons per acre compared to a hybrid that can produce about 3 tons or more.”

The Longe 5D is also a quality protein maize (QPM) variety, which combats hidden hunger by providing essential amino acids that children and lactating mothers need, according to Godfrey Asea, director of the National Crops Resources Research Institute at NARO.

“One of the initiatives we have been working on is nutritious maize, with some of the OPVs that we have released in the past being QPM varieties,” Asea said. “We are thinking of integrating more nutrient qualities such as vitamin ‘A’ in new varieties, some of which are in the release pipeline. We have also acquired genetic resources that are rich in zinc. QPM varieties, as well as varieties that are biofortified with vitamin A and zinc are very important in improving household nutrition in the future for resource-constrained maize-dependent communities.”

To make farmers aware of available seed and important attributes, marketing and promotional activities through radio, flyers, banners, field days and on-farm demonstrations come in handy. For some newer varieties, the company goes as far as issuing small seed packs to farmers so they can see for themselves how the variety performs.

From a regional outfit to the national stage

In the beginning, growth was slow for Masindi Seed due to capacity and financial constraints to sustain promotional activities. Around 2013 and 2015, the company received support from the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) to scale-up its marketing and promotional efforts, which greatly enhanced Masindi Seed’s capacity and visibility. From then on, Masindi Seed went from being just a small regional-focused outfit to a nation-wide seed firm, marketing seed as far as northern and eastern Uganda.

By working closely with farmers, Masindi Seed Company puts itself at a strategic position to understand farmers’ preferred traits better. They have found that farmers prefer traits that allow them to earn more, such as higher yield, which allows them to harvest much more maize and sell the surplus for much-needed income.

Seed that farmers can trust

Alinda Sarah, who doubles up as both a contract farmer for Masindi Seed and a large-scale grower for maize grain, agrees that obtaining the right seed that is guaranteed to germinate and offers a higher yield is a major boost to her trade.

“All I require is seed that I trust to have the attributes I want. What works for me is the seed that offers a higher yield, and can tolerate common stresses including drought, diseases and pests. This way, I can sustain my farming business,” she says.

The second attribute the farmers keep mentioning to Masindi agricultural extensionists is the maturity period, with farmers inclined to prefer faster maturing varieties, such as varieties that mature in 90 days. Ultimately, beyond some of these desirable and beneficial traits, the farmer is, before anything else, interested in the germinability of the seed they buy.

“By confirming the attributes that we tell them regarding our varieties with what they see at demo farms, the farmers trust us more,” Lusige said. “Trust is good for a business like ours and we try our best to preserve it. In the past, we have seen how some companies who lost the trust of their customers quickly went out of business.”

“Besides offering improved seed to farmers, we encourage our partner seed companies to support and teach the farmers good agronomic practices such as proper fertilizer requirements and application rates, early planting, appropriate spacing, weed control, integrated pest management and intercropping with legumes,” said Daniel Bomet, maize breeder at NARO.

Cover photo: Alinda Sarah demostrates how happy she is with the maize cob due for harvest on the farm she owns with her husband in Masindi, mid-western Uganda. (Photo: Joshua Masinde/CIMMYT)

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to widen, its effects on the agriculture sector are also becoming apparent. In countries like Ethiopia, where farming is the backbone of the nation’s economy, early preparation can help mitigate adverse effects.

Recently, Fana Broadcasting Corporate (Fana Television) organized a panel discussion on how the Ethiopian government and its partners are responding to this crisis. Analyzing this topic were Kindie Tesfaye from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), Mandefro Negussi of the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) and Esayas Lemma from the Ministry of Agriculture.

The panelists highlighted Ethiopia’s readiness in response to COVID-19. The country established a team from various institutions to work on strategies and to ensure no further food shortages occur due to the pandemic. The strategy involves the continuation of activity already started during the Bleg season — short rainy season — and the preparation for the Meher season — long rainy season — to be complemented by food production through irrigation systems during the dry season, if the crisis continues beyond September 2020.

Tesfaye indicated that CIMMYT continues to work at the national and regional levels as before, and is represented in the advisory team. One of the activities underway, he said, is the plan to use the Agro-Climate Advisory Platform to disseminate COVID-19 related information to extension agents and farmers.

Panelists agreed that the pandemic will also impact the Ethiopian farming system, which is performed collectively and relies heavily on human labor. To minimize the spread of the virus, physical distancing is highly advisable. Digital media, social media and megaphones will be used to reach out to extension agents and farmers and encourage them to apply all the necessary precaution measures while on duty. Training will also continue through digital means as face to face meetings will not be possible.

Full interview in Amharic:

Women in societies practicing wheat-based agriculture have started challenging the norm of men being sole decision-makers. They are transitioning from workers to innovators and managers, a recent study has found.

Women were adopting specific strategies to further their interests in the context of wheat-based livelihoods, the study found. The process, however, is far from straightforward.

Read more here: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/women-farmers-emerging-as-decision-makers-innovators-in-wheat-based-systems-study-72344

The COVID-19 pandemic is intensifying the impact of the twin scourges of disease and malnutrition in the world, but there is hope that new bio-fortified crops being introduced by organizations like Iowa-based Self-Help International can help combat the new coronavirus.

The Rendidor bio-fortified beans represent the first new crop introduced by Self-Help Nicaragua since 1999, when Self-Help began working in Nicaragua with the planting of Quality Protein Maize, or QPM, a high-protein corn variety that was developed at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico.

A study on the impact of providing site-specific fertilizer recommendations on fertilizer usage, productivity and welfare outcomes in Ethiopia shows that targeted fertilizer recommendations encourage fertilizer investments and lead to improved maize productivity outcomes.

Researchers from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the Department of Economics and Trinity Impact Evaluation unit (TIME), Trinity College Dublin, anticipate that the findings will provide valuable guidance to the design and delivery of improved extension services in developing countries.

Soil degradation and nutrient depletion have been serious threats to agricultural productivity and food security in Ethiopia. Over the years, soil fertility has also declined due to the increase in population size and decline in plot size. Studies have identified nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) as being the nutrients most lacking and have called for action to improve the nutrient status of soils.

In response to this, in 2007, the Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources and agricultural research centers together developed regional fertilizer recommendations. These recommendations, about fertilizer types and application rates for different crops, were disseminated to farmers through agricultural extension workers and development agents.

However, adoption of fertilizer remains low — and average application rates are generally lower than recommended. One reason for these low adoption rates is that the information provided is too broad and not tailored to the specific requirements of smallholder farmers.

A study conducted on 738 farm households randomly selected from the main maize growing areas of Ethiopia — Bako, Jimma and the East Shewa and West Gojjam zones — shows that well-targeted fertilizer recommendations can increase fertilizer usage in smallholder maize production.

Maize is one of Ethiopia’s most important crops in terms of production, productivity, and area coverage. It is a primary staple food in the major maize growing areas as well as a source of feed for animals and a raw material for industries.

The study examined the impact of providing site-specific fertilizer recommendations to farmers on fertilizer usage/adoption, farm productivity/production per hectare and consumer expenditure/welfare outcomes using a two-level cluster randomized control trial.

Tailored recommendations

The Nutrient Expert decision-support tool, developed by the International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI) in partnership with the CGIAR Research Center on Maize (MAIZE), was used to give site-specific recommendations to each farmer. With this tool, researchers offered tailored recommendations, using information on fertilizer blends available in Ethiopia, current farmers’ practices, relevant inputs and field history, and local conditions. The experiment also considered whether coupling the site-specific recommendation with crop insurance — to protect farmers’ fertilizer investment in the event of crop failure — enhanced adoption rates.

Results show that well-targeted fertilizer recommendations improve fertilizer usage and productivity of maize production. The intervention led to an increase of 5 quintals, or 0.5 tons, in average maize yields for plots in the treatment group. While the study did not find any evidence that these productivity gains led to household welfare improvements, it is likely that such improvements may take longer to realize.

The study found no differential effect of the site-specific recommendation when coupled with agricultural insurance, suggesting that the risk of crop failure is not a binding constraint to fertilizer adoption in the study setting. The findings of this research should help guide the design and delivery of improved extension services in relation to fertilizer usage and adoption in developing countries.

Cover photo: Workers harvesting green maize at Ambo Research Center, Ethiopia, 2015. (Photo: CIMMYT/ Peter Lowe)

A set of core survey questions has been developed in a bid to improve the collection and use of rural farm household data from low and middle-income countries.

Leading agricultural socioeconomists developed the 100Q report, which outlines 100 core questions to identify key indicators around agricultural activities and off-farm income, as well as key welfare indicators focusing on poverty, food security, dietary diversity, and gender equity.

The aim is to forge an international standard approach to ensure socioeconomic data sets are comparable over time and space, said Mark Van Wijk, the lead author of the recent report published through CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture.

Agricultural researchers interview hundreds of thousands of farmers across the world every year. Each survey is developed with a unique approach for a specific research question. These varied approaches to household surveys limit the impact data can have when researchers aim to reuse results to gain deeper insights.

“A standard set of questions across all farm household surveys means researchers can compare different data points to identify common drivers of poverty and food insecurity among different populations to more efficiently inform development strategies and improve livelihoods,” said Van Wijk, a senior scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

Finding common ground among data collection efforts is essential for optimizing the impact of socioeconomic data. Instead of reinventing the wheel each time researchers develop surveys, researchers in the CGIAR’s Community of Practice on Socio-Economic Data (CoP SED) formed core questions they believe should become the base of all farm household surveys to improve the ability for global analysis.

CoP SED is promoting the use of the 100Q report as building blocks in survey development through webinars with international agricultural researchers. The community is also doing further research into tagging existing survey data with ontology terms from the 100Q to improve reusability.

Harmonization key to the fair use of data

Managing shared data is becoming increasingly important as we move towards an open data world, said Gideon Kruseman, leader of the CoP SED and author of the report.

“For shareable data to be actionable, it needs to be FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable. This is the heart of the Community of Practice on Socio-Economic Data’s work.”

At the moment, international agricultural household survey data is disorganized; the proliferation of survey tools and indicators lead to datasets which are often poorly documented and have limited interoperability, explained Kruseman.

It’s estimated that CGIAR—the world’s largest network of agricultural researchers—conducts interviews with around 180,000 farmers per year. However, these interviews have lacked standardization in the socioeconomic domain for decades, leading to holes in our understanding of the agriculture, poverty, nutrition, and gender characteristics of these households.

The 100Q tool has been systematically designed to enable the quantification of interactions between different components and outcomes of agricultural systems, including productivity and human welfare at the farm and household level, said Kruseman, a Foresight and Ex-Ante Research Leader at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Streamlining survey data through the world’s largest agricultural research network

Using these building blocks should become standard practice across CGIAR. The researchers hope standardization across all CGIAR institutes will allow for easier application of big data methods for analyzing the household level data themselves, as well as for linking these data to other larger scale information sources like spatial crop yield data, climate data, market access data, and roadmap data.

Researchers from several CGIAR research organizations, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and agricultural nonprofits worked to create the common layout for household surveys and the sets of ontologies underpinning the information to be collected.

“Being able to reuse data is extremely valuable. If household survey data is readily reusable, existing data sets can be used as baselines. It allows us to easily assess how welfare indicators vary across populations and different agro-ecological and socioeconomic conditions, as well as how they may change over time,” Kruseman said.

“It also improves the effectiveness of interventions and the trade-offs between outcomes, which may be shaped by household structure, farm management, and the wider social-environmental.”

CoP SED researchers work in three groups towards improving socioeconomic data interoperability. The 100Q working group focuses on identifying key indicators and related questions that are commonly used and could be used as a standard approach to ensure data sets are comparable over time and space. The working group SEONT focuses on the development of a socioeconomic ontology with accepted standardized terms to be used in controlled vocabularies linked to socioeconomic data sets. The working group OIMS focuses on the development of a flexible and extensible, ontology-agnostic, human-intelligible, and machine-readable metadata schema to accompany socioeconomic data sets.

For more information, visit the CoP SED webpage.

Cover photo: A paddy in front of a house in Tri Budi Syukur village, West Lampung regency, Lampung province, Indonesia. (Photo: Ulet Ifansasti/CIFOR)

There is no nationwide official data on how much rice in India is grown through DSR. M L Jat, principal scientist with Mexico-based CIMMYT (International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center), estimated that about 10 per cent of India’s 44 million ha under rice cultivation is through DSR.

In the past few decades, many state governments have been encouraging farmers to move to DSR because it is easier on the environment, but without much success.

Read more here: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/back-to-basics-covid-19-labour-crunch-brings-direct-seeding-of-paddy-in-focus-72280

A new analysis by wheat scientists at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) published in Scientific Reports includes insights and genetic information that will help in the efforts to breed yellow rust resistant wheat.

Read more here: https://www.world-grain.com/articles/13959-new-analysis-to-help-in-creating-yellow-rust-resistant-wheat

A new policy brief produced by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) lays out a clear case for the benefits and importance of conservation agriculture, and a road map for accelerating its adoption in Eastern India.

A collaborative effort by research and policy partners including ICAR, the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences (NAAS), The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), and national academic and policy institutions, the brief represents the outputs of years of both rigorous scientific research and stakeholder consultations.

Eastern India — an area comprising seven states — is one of the world’s most densely populated areas, and a crucial agricultural zone, feeding more than a third of India’s population. The vast majority — more than 80% — of its farmers are smallholders, earning on average, just over half the national per capita income.

Conservation agriculture (CA) consists of farming practices that aim to maintain and boost yields and increase profits while reversing land degradation, protecting the environment and responding to climate change. These practices include minimal mechanical soil disturbance, permanent soil cover with living or dead plant material, and crop diversification through rotation or intercropping. A number of studies have shown the success of conservation agriculture in combatting declining factor productivity, deteriorating soil health, water scarcity, labor shortages, and climate change in India.

The road map lists recommended steps for regional and national policy makers, including

Read the full policy brief here:

Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Intensification in Eastern India

Partners include the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences (NAAS), the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), the Trust for Advancement of Agricultural Sciences (TAAS), the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA), Dr. Rajendra Prasad Central Agricultural University, Bihar Agricultural University, and the Department of Agriculture of the state of Bihar.

The machine saves farmers the burden of physically removing maize from combs, a tedious, time wasting and costly exercise that is practiced by at least 85 per cent of smallholder farmers in the country according to a research dubbed ‘maize production, challenges and experience of smallholder farmers in East Africa by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Read more here: https://farmbizafrica.com/market-place/12-machinery/999-inexpensive-maize-sheller-saves-farmers-tens-of-hours

Can Africa’s smallholder farmers adopt and reap the benefits of farm mechanization? The Farm Mechanization and Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Intensification (FACASI) team set out in 2013 to test this proposition. With the project nearing closure, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) project leader Frédéric Baudron believes the answer is yes.

“We have demonstrated that small-scale mechanization is a pathway to sustainable intensification and rural transformation, and can have positive gender outcomes as well,” he explained.

Here are some of the key lessons learned along the way, according to the people involved.

1. Appropriate mechanization is essential

With many farms in Africa measuring no more than two hectares, FACASI focused on bringing two-wheel tractors to regions where smallholdings dominate, especially in Zimbabwe and Ethiopia. For most small farmers, conventional farm machinery is out of reach due to its size, costs, and the skills needed to operate it. The typical path to mechanization would be for farmers to consolidate their farms, which could lead to social and environmental upheaval. Instead, the FACASI team scaled-down the equipment to suit the local context.

FACASI has obtained evidence to dispel commonly held myths about farm power in smallholder farming systems,” said Eric Huttner, research program manager for crops at the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR).

2. Test, develop and adapt technologies… together

From start to finish, the project tested and developed technologies in collaboration with farmers, local manufacturers, engineers, extension agents. Together, they adapted and refined small-scale machinery used in other parts of the world to accommodate the uneven fields and hard soils of African smallholder farms. This co-construction of technologies helped cultivate a stronger sense of local ownership and buy-in.

“We gained many valuable insights by continuously refining technologies in the context of efficiency, farmer preference and needs,” said Bisrat Getnet, FACASI national project coordinator in Ethiopia, and director of the Agricultural Engineering Research Department in the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR).

3. Make it useful

The basic two-wheel tractor is a highly flexible and adaptable technology, which can be used to mechanize a range of on-farm tasks throughout the seasons. With the right attachments, the tractor makes short work of sowing, weeding, harvesting, shelling, water pumping, threshing and transportation.

“This multi-functional feature helps to ensure the tractor is useful at all stages of the annual farming cycle, and helps make it profitable, offsetting costs,” said Raymond Nazare, FACASI national project coordinator in Zimbabwe and lecturer at the Soil and Engineering Department of the University of Zimbabwe.

4. Less pain, more profit

Reducing the unnecessary drudgery of smallholder farming can be financially rewarding and open new doors. Mechanization can save farmers the costs of hiring additional labor, and vastly reduce the time and effort of many post-harvest tasks — often done by women — such as transport, shelling and grinding. FACASI researchers demonstrated the potential for mechanization to reduce this onerous labor, allowing women to channel their time and energy into other activities.

5. New, inclusive rural business models

New technologies need reliable supply chains and affordable support services. The FACASI team supported leasing and equipment-sharing schemes, trained people to operate and maintain machinery, and encouraged individuals and groups to become service providers. These efforts often focused on giving youth and women new business opportunities.

“The project demonstrated that small mechanization can create profitable employment,” said Tirivangani Koza, of Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Water and Rural Resettlement.

“Women and youth are using small mechanization to grow profitable businesses,” said Alice Woodhead in Australia.

“They have advanced from dependent family members to financially independent entrepreneurs. Their new skills, such as servicing the tractors, marketing and shelling, have increased their family’s income. FACASI has also inspired community members to launch aligned businesses such as shelling services, inventing new two-wheel tractor implements for the growing customer base, or becoming artisan mechanics. In some districts, the two-wheel tractors are starting to create a cycle of innovation, business development, food diversification and sustainable economic growth,” she said.

6. Respond to farmer demands

Although the FACASI team set out to promote mechanization as a way to help farmers take up conservation agriculture techniques such as direct seeding, they opened the Pandora’s box for other beneficial uses. By the project’s end, it was clear that transport and mechanization of post-harvest tasks like shelling and threshing, had become far more popular among farmers than mechanization of crop production. This result is a sign of the team’s success in demonstrating the value of small-scale mechanization, and adapting technologies to respond to farmers’ needs.

7. Embrace new research models

Agricultural research for development has long forgotten about labour and mechanization issues; the FACASI team helped put these front and center by involving engineers, business enterprises, agriculturalists, and partners from across the supply chain.

“FACASI demonstrates an important change in how to do agricultural research to achieve meaningful impacts,” Woodhead said.

“Rather than focus only on the farm environment and on extension services, they worked from the outset with partners across the food, agriculture and manufacturing sectors, as well as with the public institutions that can sustain long-term change. The project’s results are exciting because they indicate that sustainable growth can be achieved by aligning conservation agriculture goals, institutions and a community’s business value propositions,” she explained.

What’s next?

Although the project has ended, its insights and lessons will carry on.

“We have built a solid proof of concept. We know what piece of machinery works in a particular context, and have tested different delivery models to understand what works where,” explained Frédéric Baudron.

“We now need to move from piloting to scaling. This does not mean leaving all the work to development partners; research still has a big role to play in generating evidence and making sure this knowledge can be used by local manufacturers, engineers, local dealers and financial institutions,” he said.

As an international research organization, CIMMYT is strategically placed to provide critical answers to farming communities and the diversity of actors in the mechanization value chain.

A number of other organizations have taken up the mantle of change, supporting mechanization as part of their agricultural investments. This includes an initiative supported by the German Development Agency (GIZ) in Ethiopia, an IFAD-supported project to boost local wheat production in Rwanda and Zambia, and an intervention in Zimbabwe supported by the Zimbabwe Resilience Building Fund.

“ACIAR provided us generous and visionary support, at a time when very few resources were going to mechanization research in Africa,” Baudron acknowledged. “This allowed CIMMYT and its partners from the national research system and the private sector to develop unique expertise on scale-appropriate mechanization. The legacy of FACASI will be long-lived in the region,” he concluded.

Cover photo: Starwheel planter in Zimbabwe. (Photo: Jérôme Bossuet/CIMMYT)

The agricultural market has been suffering since the government of Nepal imposed a lockdown from March 23, 2020 to limit the spread of COVID-19 in the country. A month after the lockdown, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) conducted a rapid assessment survey to gauge the extent of disruptions of the lockdown on households from farming communities and agribusinesses.

As part of the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, CIMMYT researchers surveyed over 200 key stakeholders by phone from 26 project districts. These included 103 agrovet owners and 105 cooperative managers who regularly interact with farming communities and provide agricultural inputs to farmers. The respondents served more than 300,000 households.

The researchers targeted maize growing communities for the survey since the survey period coincided with the primary maize season.

Key insights from the survey

The survey showed that access to maize seed was a major problem that farmers experienced since the majority of agrovets were not open for business and those that were partially open — around 23% — did not have much customer flow due to mobility restrictions during the lockdown.

The stock of hybrid seed was found to be less than open pollinated varieties (OPVs) in most of the domains. Due to restrictions on movement during the entire maize-planting season, many farmers must have planted OPVs or saved seeds.

Access to fertilizers such as urea, DAP and MOP was another major problem for farmers since more than half of the cooperatives and agrovets reported absence of fertilizer stock in their area. The stock of recommended pesticides to control pests such as fall armyworm was reported to be limited or out of stock at the cooperatives and agrovets.

Labor availability and use of agricultural machineries was not seen as a huge problem during the lockdown in the surveyed districts.

It was evident that food has been a priority for all household expenses. More than half of the total households mentioned that they would face food shortages if the lockdown continues beyond a month.

During the survey, around 36% of households specified cash shortages to purchase agricultural inputs, given that a month had already passed since the lockdown began in the country. The majority of the respondents reported that the farm households were managing their cash requirements by borrowing from friends and relatives, local cooperatives or selling household assets such as livestock and agricultural produces.

Most of the households said that they received food rations from local units called Palikas, while a small number of Palikas also provided subsidized seeds and facilitated transport of agricultural produce to market during the lockdown. Meanwhile, the type of support preferred by farming communities to help cope with the COVID-19 disruptions — ranging from food rations, free or subsidized seed, transportation of fertilizers and agricultural produce, and provision of credit — varied across the different domains.

The survey also assessed the effect of lockdown on agribusinesses like agrovets who are major suppliers of seed, and in a few circumstances sell fertilizer to farmers in Nepal. As the lockdown enforced restrictions on movement, farmers could not purchase inputs from agrovets even when the agrovets had some stock available in their area. About 86% of agrovets spoke of the difficulty to obtain supplies from their suppliers due to the blockage of transportation and product unavailability, thereby causing a 50-90% dip in their agribusinesses.

Immediate actions to consider

Major takeaways from this survey are as follows:

The survey findings were presented and shared with the government, private sector, development partner organizations and project staff over a virtual meeting. This report will serve as a resource for the project and various stakeholders to design their COVID-19 response and recovery strategy development and planning.

June marks the start of the rice growing season in India’s breadbasket but on the quiet fields of Haryana and Punjab you wouldn’t know it.

Usually the northwestern Indian states are teeming with migrant laborers working to transplant rice paddies. However, the government’s swift COVID-19 lockdown measures in late March triggered reverse migration, with an estimated 1 million laborers returning to their home states.

The lack of migrant workers has raised alarms for the labor-dependent rice-wheat farms that feed the nation. Healthy harvests are driven by timely transplanting of rice and, consequently, by the timely sowing of the succeeding wheat crop in rotation.

Without political support for alternative farming practices, crop losses from COVID-19 labor disruptions could reach $1.5 billion and significantly diminish the country’s grain reserves, researchers from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) warned.

Researchers also fear delayed rice transplanting could encourage unsustainable residue burning as farmers rush to clear land in the short window between rice harvest and wheat sowing. Increased burning in the fall will exacerbate the COVID-19 health risk by contributing to the blanket of thick air pollution that covers much of northwest India, including the densely populated capital region of New Delhi.

Both farmers and politicians are showing increased interest in farm mechanization and crop diversification as they respond to COVID-19 disruptions, said M.L. Jat, a CIMMYT scientist who coordinates sustainable intensification programs in northwestern India.

“Farmers know the time of planting wheat is extremely important for productivity. To avoid production losses and smog-inducing residue burning, alternative farm practices and technologies must be scaled up now,” Jat said.

The time it takes to manually transplant rice paddies is a particular worry. Manual transplanting accounts for 95% of rice grown in the northwestern regions. Rice seedlings grown in a nursery are pulled and transplanted into puddled and leveled fields — a process that takes up to 30 person-days per hectare, making it highly dependent on the availability of migrant laborers.

Even before COVID-19, a lack of labor was costing rice-wheat productivity and encouraging burning practices that contribute to India’s air pollution crisis, said CIMMYT scientist Balwinder Singh.

“Mechanized sowing and harvesting has been growing in recent years. The COVID-19 labor shortage presents a unique opportunity for policymakers to prioritize productive and environmentally-friendly farming practices as long term solutions,” Singh said.

Sustainable practices to cope with labor bottlenecks

CIMMYT researchers are working with national and state governments to get information and technologies to farmers, however, there are significant challenges to bringing solutions to scale in the very near term, Singh explained.

There is no silver bullet in the short term. However, researchers have outlined immediate and mid-term strategies to ensure crop productivity while avoiding residue burning:

Delayed or staggered nursery sowing of rice: By delaying nursery sowing to match delays in transplanting, yield potential can be conserved for rice. Any delay in transplanting rice due to labor shortage can reduce the productivity of seedlings. Seedling age at transplanting is an important factor for optimum growth and yield.

“Matching nursery sowing to meet delayed transplanting dates is an immediate action that farmers can take to ensure crop productivity in the short term. However, it’s important policymakers prioritize technologies, such as direct seeders, that contribute to long term solutions,” Singh said.

Direct drilling of wheat using the Happy Seeder: Direct seeding of wheat into rice residues using the Happy Seeder, a mechanized harvesting combine, can reduce the turnaround time between rice harvest and wheat sowing, potentially eliminating the temptation to burn residues.

“Identifying the areas with delayed transplanting well in advance should be a priority for effectively targeting the direct drilling of wheat using Happy Seeders,” said Jat. The average farmer who uses the Happy Seeder can generate up to 20% more profits than those who burn their fields, he explained. “Incentivizing farmers through a direct benefit transfer payment to adopt ‘no burn’ practices may help accelerate transitions.”

Directly sown rice: Timely planting of rice can also be achieved by adopting dry direct seeding of rice using mechanized seed-cum-fertilizer planters. In addition to reducing the labor requirement for crop establishment, dry direct seeding allows earlier rice planting due to its lower water requirement for establishment. Direct-seeded rice also matures earlier than puddled transplanted rice. Thus, earlier harvesting improves the chance to sow wheat on time.

“CIMMYT researchers are working with the local mechanical engineers on rolling out simple tweaks to enable the Happy Seeder to be used for direct rice seeding. The existing availability of Happy Seeders in the region will improve the speed direct rice sowing can be adopted,” Jat said.

Crop diversification with maize: Replacing rice with maize in the monsoon season is another option to alleviate the potential shortage of agricultural labor due to COVID-19, as the practice of establishing maize by machine is already common.

“Research evidence generated over the past decade demonstrates that maize along with modern agronomic management practices can provide a profitable and sustainable alternative to rice,” Jat explained. “The diversification of rice with maize can potentially contribute to sustainability that includes conserving groundwater, improving soil health and reducing air pollution through eliminating residue burning.”

Getting innovations into farmers’ fields

Rapid policy decisions by national and state governments on facilitating more mechanized operations in labor-intensive rice-wheat production regions will address labor availability issues while contributing to productivity enhancement of succeeding wheat crop in rotation, as well as overall system sustainability, said ICAR’s deputy director general for agricultural extension, AK Singh.

The government is providing advisories to farmers through multiple levels of communications, including extension services, messaging services and farmer collectives to raise awareness and encourage adoption.

Moving toward mechanization and crop diversity should not be viewed as a quick fix to COVID-19 related labor shortages, but as the foundation for long-term policies that help India in achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals, said ICAR’s deputy director general for Natural Research Management, SK Chaudhari.

“Policies encouraging farming practices that save resources and protect the environment will improve long term productivity of the nation,” he said.

Northwestern India is home to millions of smallholder farmers making it a breadbasket for grain staples. Since giving birth to the Green Revolution, the region has continued to increase its food production through rice and wheat farming providing bulk of food to the country.

This high production has not come without shortfalls, different problems like a lowering water table, scarcity of labor during peak periods, deteriorating soil health, and air pollution from crop residue burning demands some alternative methods to sustain productivity as well as natural resources.

Cover photo: A farmer uses a tractor fitted with a Happy Seeder. (Photo: Dakshinamurthy Vedachalam/CIMMYT)

In response to increasing labor scarcity and costs, growth in mechanized wheat and rice harvesting has fueled farm prosperity and entrepreneurial opportunity in the poorest parts of Nepal, researchers from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) have recorded.

Farmers are turning to two-wheeled tractor-mounted reaper-harvesters to make up for the lack of farm labor, caused by a significant number of rural Nepalese — especially men and youth — migrating out in search of employment opportunities.

For Nandalal Oli, a 35-year-old farmer from Bardiya in far-west Nepal, investing in a mechanized reaper not only allowed him to avoid expensive labor costs that have resulted from out-migration from his village, but it also provided a source of income offering wheat and rice harvesting services to his neighbors.

“The reaper easily attaches on my two-wheel tractor and means I can mechanically cut and lay the wheat and rice harvests,” said Oli, the father of two. “Hiring help to harvest by hand is expensive and can take days but with the reaper attachment it’s done in hours, saving time and money.”

Oli was first introduced to the small reaper attachment three years ago at a farmer exhibition hosted by Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), funded through USAID. He saw the reaper as an opportunity to add harvesting to his mechanization business, where he was already using his two-wheel tractor for tilling, planting and transportation services.

Prosperity powers up reaper adoption

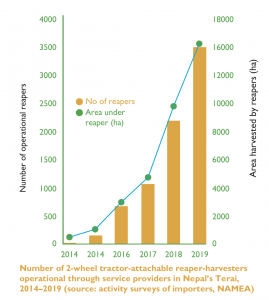

Over 4,000 mechanized reapers have been sold in Nepal with more than 50% in far and mid-west Nepal since researchers first introduced the technology five years ago. The successful adoption — which is now led by agricultural machinery dealers that were established or improved with CSISA’s support — has led nearly 24,000 farmers to have regular access to affordable crop harvesting services, said CIMMYT agricultural economist Gokul Paudel.

“Reapers improve farm management, adding a new layer of precision farming and reducing grain loss. Compared to manual harvesting mechanized reapers improve farming productivity that has shown to significantly increase average farm profitability when used for harvesting both rice and wheat,” he explained.

Nearly 65% of Nepal’s population works in agriculture, yet this South Asian country struggles to produce an adequate and affordable supply of food. The research indicated increased farm precision through the use of mechanized reapers boosts farm profitability by $120 a year when used for both rice and wheat harvests.

Oli agreed farmers see the benefit of his harvesting service as he has had no trouble finding customers. On an average year he serves 100 wheat and rice farmers in a 15 kilometer radius of his home.

“Investing in the reaper harvester worked for me. I earn 1,000 NRs [about $8] per hour harvesting fields and was able to pay off the purchase in one season. The added income ensures I can stay on top of bills and pay my children’s school fees.”

Farmers who have purchased reapers operate as service providers to other farms in their community, Paudel said.

“This has the additional benefit of creating legitimate jobs in rural areas, particularly needed among both migrant returnees who are seeking productive uses for earnings gained overseas that, at present, are mostly used for consumptive and unproductive sectors.”

“This additional work can also contribute to jobs for youth keeping them home rather than migrating,” he said.

The adoption rate of the reaper harvester is projected to reach 68% in the rice-wheat systems in the region within the next three years if current trends continue, significantly increasing access and affordability to the service.

Private and public support for mechanized harvester key to strong adoption

Achieving buy-in from the private and public sector was essential to the successful introduction and uptake of reaper attachments in Nepal, said Scott Justice, an agricultural and rural mechanization expert with the CSISA project.

Off the back of the popularity of the two-wheel tractor for planting and tilling, 22 reaper attachments were introduced by the researchers in 2014. Partnering with government institutions, the researchers facilitated demonstrations led by the private sector in farmers’ fields successfully building farmer demand and market-led supply.

“The reapers were introduced at the right place, at the right time. While nearly all Terai farmers for years had used tractor-powered threshing services, the region was suffering from labor scarcity or labor spikes where it took 25 people all day to cut one hectare of grain by hand. Farmers were in search of an easier and faster way to cut their grain,” Justice explained.

“Engaging the private and public sector in demonstrating the functionality and benefits of the reaper across different districts sparked rapidly increasing demand among farmers and service providers,” he said.

Early sales of the reaper attachments have mostly been directly to farmers without the need for considerable government subsidy. Much of the success was due to the researchers’ approach engaging multiple private sector suppliers and the Nepal Agricultural Machinery Entrepreneurs’ Association (NAMEA) and networks of machinery importers, traders, and dealers to ensure stocks of reapers were available at local level. The resulting competition led to 30-40% reduction in price contributing to increasing sales.

“With the technical support of researchers through the CSISA project we were able to import reaper attachments and run demonstrations to promote the technology as a sure investment for farmers and rural entrepreneurs,” said Krishna Sharma from Nepal Agricultural Machinery Entrepreneurs’ Association (NAMEA).

From 2015, the private sector capitalized on farmers’ interest in mechanized harvesting by importing reapers and running their own demonstrations and several radio jingles and sales continued to increase into the thousands, said Justice.

Building entrepreneurial capacity along the value chain

Through the CSISA project private dealers and public extension agencies were supported in developing training courses on the use of the reaper and basic business skills to ensure long-term success for farmers and rural entrepreneurs.

Training was essential in encouraging the emergence of mechanized service provision models and the market-based supply and repair chains required to support them, said CIMMYT agricultural mechanization engineer Subash Adhikari.

“Basic operational and business training for farmers who purchased a reaper enabled them to become service providers and successfully increased the access to reaper services and the amount of farms under improved management,” he said.

As commonly occurs when machinery adoption spreads, the availability of spare parts and repairs for reapers lagged behind sales. Researchers facilitated reaper repair training for district sales agent mechanics, as well as providing small grants for spare parts to build the value chain, Adhikari added.

Apart from hire services, mechanization creates additional opportunities for new business with repair and maintenance of equipment, sales and dealership of related businesses including transport and agro-processing along the value chain.

The Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA) aims to sustainably increase the productivity of cereal based cropping systems to improve food security and farmers’ livelihoods in Nepal. CSISA works with public and private partners to support the widespread adoption of affordable and climate-resilient farming technologies and practices, such as improved varieties of maize, wheat, rice and pulses, and mechanization.

Cover photo: A farmer uses a two-wheel tractor-mounted reaper to harvest wheat in Nepal. (Photo: Timothy J. Krupnik/CIMMYT)