It is an important year for biofortification: 2023 will mark the 20th anniversary of this nutrition-agricultural innovation, for which its pioneers were awarded the World Food Prize.

More than three billion people around the world, mostly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, cannot afford a nourishing, diverse diet that provides enough vitamins and minerals (micronutrients). While efforts to pursue dietary diversity—the accepted gold standard for optimal health—must continue, a healthy diet remains out of reach for a vast majority of the world’s population.

The consequences are dire. A staggering two billion people get so little essential micronutrients from their diets that they suffer from “hidden hunger”, the often-invisible scourge of micronutrient malnutrition.

To combat hidden hunger requires a range of context-specific combinations of evidence-based interventions that complement each other, including dietary diversification, supplementation, commercial food fortification, biofortification, and public health measures (like safe water, sanitation, and breastfeeding).

There is no single solution to ensure everyone, everywhere has access to an affordable, diverse, and healthy diet. Biofortification is one of the many important solutions being implemented by global research partners working together across CGIAR to ensure a food-secure future for all.

It is imperative to implement interventions that are practical and accessible in regions and among people most affected by hidden hunger, such as women and children in rural farming families in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), who primarily eat what they grow. This is particularly important during periods of rapid growth and development like in the first 1,000 days of life, after which the negative impacts of an insufficient diet become largely irreversible.

In this 20th anniversary year of HarvestPlus and biofortification, we review biofortification’s role, advantages, and scale as an essential part of CGIAR-wide effort to improve global nutrition.

Biofortification: A Complementary Approach to Reduce Malnutrition

“Biofortified crops are going to be game-changers in dealing with… malnutrition in our world today.”

Dr. Adesina, President of the African Development Bank, World Food Prize Laureate

Staple food crops contain fewer vitamins and minerals than animal-based foods and some vegetables and fruits. Yet wheat, maize, rice, cassava, sweet potato, beans, pearl millet, and other staple foods make up the foundation of most diets around the world, and should therefore be as nutritious as possible.

Staple foods also offer nutritional protection against food systems shocks, especially for vulnerable populations who are unable to access a healthy and diverse diet, and whose reliance on staple food crops increases during times of crises. Through biofortification, staple crops can contribute a high proportion of the micronutrients needed for good health and nutrition.

Biofortification efforts to date have focused mainly on using conventional plant breeding and agronomic techniques to add more of the micronutrients most lacking in diets around the world—zinc, iron, and vitamin A— into staple crops. This approach acknowledges that many poor people cannot afford or access the variety of non-staple foods they need for optimal health, and are often underserved by other large-scale public health nutrition interventions.

“[Biofortified] crops provide a sustainable source of much needed nutrients to rural communities.”

Prof. Watts, Chief Scientific Advisor and Director for Research and Evidence, UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office

Eating poor-quality, and often unsafe, food perpetuates a cycle of poverty, infection, and malnutrition. Enriching nutrients into staple crops that farmers are already eating provides a safety net against severe levels of deficiency and helps mitigate challenges of nutrition insecurity due to climate change.

CGIAR transdisciplinary, participatory, and action-oriented research and innovations to improve nutritional outcomes, including biofortification, are making a vital contribution towards realizing Sustainable Development Goal 2 to end hunger and all forms of malnutrition.

Meeting Nutritional Needs

Biofortified crops are targeted mostly at rural food systems in LMICs, where deficiencies in vitamin A, iron, and zinc are highly prevalent. Young children, adolescent girls, and women are the priority groups for biofortification because their relatively high micronutrient needs predispose them to hidden hunger.

The scientific body of evidence supporting biofortification spans over two decades. Each biofortified crop is the subject of extensive research to evaluate its intrinsic nutritional value and its potential impacts on human nutrition and health.

Vitamin A orange sweet potato (OSP) was the first biofortified staple to be delivered at scale and evaluated in sub-Saharan Africa, a joint effort by HarvestPlus, the International Potato Center, and the International Food Policy Research Institute. It has very high levels of vitamin A (traditional white varieties contain none) and long-term studies indicate it can help reduce diarrhea in children and is a cost-effective way to improve population vitamin A intake, thereby improving child and maternal health and reducing the likelihood of vitamin A deficiency. Breeding efforts are now simultaneously increasing the iron content of OSP, to deliver more of multiple stacked micronutrients.

Evidence from additional randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that nutrient-enhanced staple crops generate positive direct and indirect health effects on multiple age groups, for example:

Supplementation studies have clearly shown that improvements in micronutrient status, particularly zinc, vitamin A, and iron status, generate improvements in immunity, growth, and multiple other dimensions of good health. The improvements are not specific to how the micronutrients are delivered (e.g., by food or pills), but rather due to positive changes in nutritional status.

Breeding for Improved Grain Yield and Nutritional Quality

“The reason for growing these varieties, is better yield, more profitability and better zinc nutrition for our families.”

— Mr Tariq, Pakistani farmer

Adoption of biofortification is demand driven. All released biofortified varieties are agronomically competitive in the agricultural zone(s) for which they were developed, relative to the varieties farmers already grow.

Crop breeding efforts are responsive to the expressed priorities and preferences of farming families and their countries. High yields are among the traits considered non-negotiable by breeders and farmers alike, and are a driver for national authorities to approve the release of new varieties in their countries to farmers to grow them.

Innovative breeders at CGIAR centers and National Agricultural Research Extension Systems have successfully been able to achieve exceptional yield and nutrition gains simultaneously in biofortified varieties, a benefit that is realized by farmers.

“[Nyota, an iron bean] can easily give me over 3 tons per hectare, as compared to other varieties that yield about 2 tons.”

— Mr Burde, Kenyan seed producer

Breeding pipelines are dynamic and always adapting to new stresses. Nutrient-enriched varieties of crops are continuously improved by breeders who breed varieties for progressively higher levels of micronutrients, which are also agronomically competitive (e.g., disease and pest resistant), well adapted to a wide range of climatic conditions (e.g., drought and heat tolerant), and exhibit food quality traits desired by farmers, food processors, and consumers (e.g., fast cooking time and good taste).

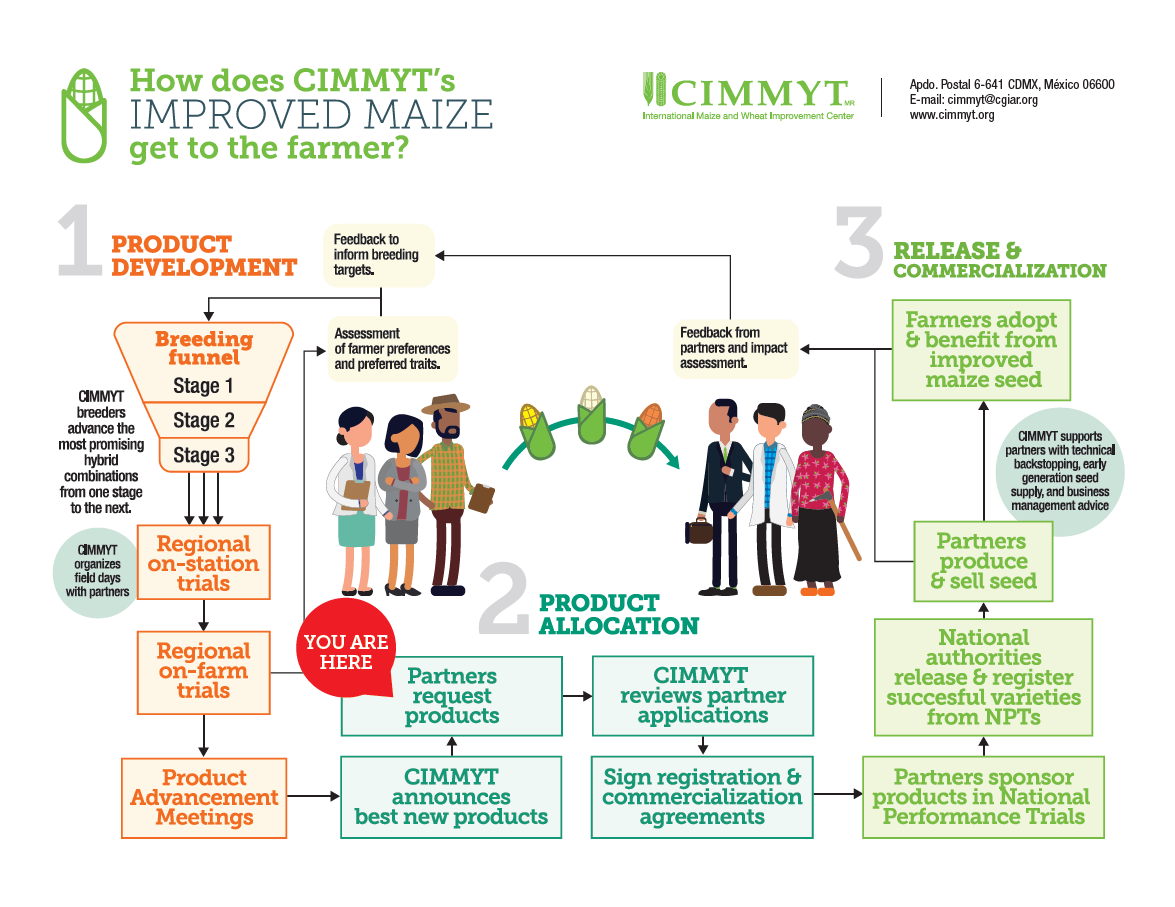

In Pakistan, one of the highest wheat-consuming countries in the world, the zinc wheat variety Akbar-2019 is now a ‘mega-variety’. It provides 30 percent more zinc and 8-10 percent higher yield than previous popular varieties. Developed by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in partnership with HarvestPlus, and released by the Wheat Research Institute of the Ayub Agricultural Research Institute, Faisalabad, Akbar-2019 is also resistant to rusts and well adapted to a range of sowing dates. Farmers attest to the good quality of the chapatti (flat bread) made from its flour. Akbar-2019 is already being grown on more than three million hectares of land—and soon an estimated 100 million people will eat chapatti made from its flour and reap the benefits of added zinc in their diets.

“My father-in-law… has expressed a desire to continue growing only biofortified zinc wheat from now on. In addition to the grain quality, the plants also grow well in tough geographical conditions.”

— Ms Devi, Indian farmer

In Nigeria, HarvestPlus and partners including the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture have developed varieties of vitamin A cassava with multiple traits attractive for farmers. Survey data indicates vitamin A cassava varieties have an average fresh root yield of 20.5 metric tons per hectare (MT/Ha), well above the average yield of 10.2 MT/Ha of other improved but non-biofortified varieties. Nearly 2.1 million farmers are growing vitamin A cassava in Nigeria, providing added dietary vitamin A to over 10 million people in a country where vitamin A deficiency is a severe, yet preventable, public health problem.

Farmers carefully consider yield, profitability, stress tolerance, taste, and more when selecting the varieties they grow—over 17 million farming households chose to grow biofortified varieties in 2022, enriching the diets of over 86 million people.

Contributing To Agricultural Diversity

To establish new crops with higher levels of micronutrients, breeders tap into the spectrum of genetic diversity stored within global plant gene banks to find nutrient-dense qualities from underutilized plant species (including wild species or those naturally evolved in certain geographic areas).

Through breeding for improved nutrition, biofortification also transfers otherwise untapped variation for traits other than micronutrients into newly developed crops, increasing the genetic agrobiodiversity not only in biofortified varieties, but also non-biofortified varieties derived from crossing micronutrient-dense plant ‘parents’ to produce high micronutrient ‘offspring’.

Micronutrient genes are not subject to erosion in the breeding process (as genes are for disease or pest resistance), like the dwarfing genes in wheat and rice that catalyzed the green revolution.

CGIAR has committed to mainstreaming improved nutrient traits in most of their breeding lines through crop breeding, given its proven cost-effective and sustainable approach to enriching staple food crops.

Committed to Scaling

Governments and other “Our aim should be to make every family farm a biofortified farm.”

— Dr MS Swaminathan, World Food Prize Laureate, Father of Indian Green Revolution

HarvestPlus partners, collaborators, and advocates support country-level initiatives that promote the integration of biofortified seeds, crops, and foods into local, national, and regional policies and programs. These collective efforts and alliances are the catalyst behind the scale up to over 86 million people in farming households eating nutrient-enriched foods in 2022, 22% more than in 2021.

In 2022, a declaration adopted by the African Union to scale up food fortification and biofortification in Africa—to make nutrient-rich foods sustainably available, accessible, and affordable—was centered on ensuring healthy diets reach those who need them most.

The Government of DR Congo has committed to scaling biofortified crop adoption and production, and its integration into the wider food system. Biofortified crops are included as one component of a wide-reaching, multi-sectoral nutrition program, funded with a loan from the World Bank.

In India, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research established minimum levels of iron and zinc to be bred into national varieties of pearl millet. The All-India Coordinated Research Project on Pearl Millet encouraged National Agricultural Research Systems to begin breeding programs for micronutrients along with higher yields in 2014. Joint efforts by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics and HarvestPlus to enhanced the levels of iron in pearl millet have brought notable endorsement of biofortification by the Honorable Prime Minister Modi as a solution to address malnutrition.

The Copenhagen Consensus, a global research think-tank and policy advisory group, assessed biofortification and concluded for every USD 1 spent on biofortification, as much as USD 17 in benefits could be generated, and deemed biofortification, supplementation, and fortification as some of the smartest ways to spend money and advance global welfare.

Systematic reviews and ex-ante (before intervention) analyses of several micronutrient-crop and country scenarios have shown that biofortification is highly cost-effective when measured by the World Bank’s criteria of cost per Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) saved. These analyses show biofortified crops to be in the range of USD 15-20 per DALY saved—far below the World Bank’s cost-effectiveness threshold of USD 270 per DALY.

“Patience, perseverance, and vision are required to achieve the cost-effectiveness of linking agriculture and nutrition in general, and biofortification in particular. The donors to the CGIAR system realized this by continuing investments well after the 20th anniversaries of CIMMYT and the International Rice Research Institute.” — Howarth (Howdy) Bouis, HarvestPlus Founding Director, World Food Prize Laureate

Global Benefit

The number of vulnerable rural families and communities growing and benefiting from nutrient-enriched crops has significantly increased year over year. Today, over 86 million people in farming households are eating biofortified foods—progressing rapidly towards 100 million in later 2023.

Eliminating malnutrition requires multiple solutions, and biofortification is an extremely important part of CGIAR’s efforts in pursuit of this goal.

Research has proven biofortification to be an efficacious, cost-effective, and scalable innovation that can play a pivotal role in transforming food systems to deliver affordable and accessible nutritious food for all.

This story was originally posted by HarvestPlus: Twenty Years of Enriching Diets with Biofortification.

Cover photo: Experimental harvest of provitamin A-enriched orange maize, Zambia. (Photo: CIMMYT)