CIMMYT E-News, vol 4 no. 8, August 2007

Faster, cheaper, more efficient: gift from DuPont helps CIMMYT scientists look for genes in wheat and maize—and gives breeders an affordable tool to help select the best.

A quiet revolution is taking place in CIMMYT’s biotechnology labs. The team has just received a new generation of genotyping machines. These semi-automated work-horses will make it much easier to determine whether breeding lines contain specific useful genes. It is hoped that this will help maize and wheat breeders—through a process known as marker-assisted selection (MAS)—to make breeding more effective and get crop varieties with valuable traits to poor farmers more quickly.

A quiet revolution is taking place in CIMMYT’s biotechnology labs. The team has just received a new generation of genotyping machines. These semi-automated work-horses will make it much easier to determine whether breeding lines contain specific useful genes. It is hoped that this will help maize and wheat breeders—through a process known as marker-assisted selection (MAS)—to make breeding more effective and get crop varieties with valuable traits to poor farmers more quickly.

Traditionally, the only way to find out whether the offspring from a particular cross have inherited useful characteristics, such as drought tolerance, disease resistance, or grain quality, has been to grow them in the field and evaluate the adult plants. MAS can speed up the breeding process, since it makes it possible to track the presence of desired genes in every generation. This does not bypass the need for field evaluation, but can greatly improve the efficiency of the process. “Field screening takes time, space, and resources, and our capacity is limited,” explains CIMMYT maize breeder Gary Atlin, “but with MAS we could use resources more effectively, zeroing in on the best lines to test in the field and filtering out those that haven’t inherited the characteristics we need.”

When researchers want to find out whether a particular line of wheat or maize has the useful version of a gene (for example, disease resistance rather than disease susceptibility), they use nearby, identifiable sections of DNA known as markers, labeled with a fluorescent dye. Different versions of markers and genes are called alleles. DNA that is close together on the chromosome tends to stay together over generations, so a specific allele of a marker will be routinely inherited alongside the desired allele of a nearby gene. Using the new capillary electrophoresis genotyping machines, the sample is forced along a narrow capillary tube under the influence of an electric current. A laser at the end of the tube detects the different alleles of the fluorescent markers, indicating to the scientist whether the sample contains the allele they want.

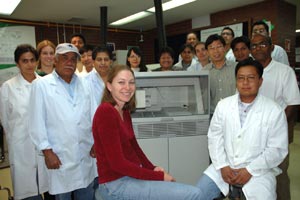

The two ABI 3700 machines have been generously donated to CIMMYT by DuPont through its Pioneer Hi-Bred seed business, reflecting a fruitful collaborative relationship of more than a decade’s standing. Until now, CIMMYT has run most of its marker-assisted selection work on manual, gel-based electrophoresis apparatuses. In addition, analyses of genetic relationships between different wheat or maize lines have been run on older ABI genotyping machines, including two based on the previous, much slower generation of gel-based machines. The new machines can handle many more samples—96 each at a time—but it’s the savings in hands-on time that makes the real difference. “There’s no comparison,” says Marilyn Warburton, Head of CIMMYT’s Applied Biotechnology Center. “It will take us ten minutes to load one of these new machines, whereas it takes about four hours to make and load a manual electrophoresis gel.”

The two ABI 3700 machines have been generously donated to CIMMYT by DuPont through its Pioneer Hi-Bred seed business, reflecting a fruitful collaborative relationship of more than a decade’s standing. Until now, CIMMYT has run most of its marker-assisted selection work on manual, gel-based electrophoresis apparatuses. In addition, analyses of genetic relationships between different wheat or maize lines have been run on older ABI genotyping machines, including two based on the previous, much slower generation of gel-based machines. The new machines can handle many more samples—96 each at a time—but it’s the savings in hands-on time that makes the real difference. “There’s no comparison,” says Marilyn Warburton, Head of CIMMYT’s Applied Biotechnology Center. “It will take us ten minutes to load one of these new machines, whereas it takes about four hours to make and load a manual electrophoresis gel.”

As well as being much quicker and less labor-intensive, capillary electrophoresis makes it possible to test for more than one marker and run more than one sample at once in each tube. By using different colors of fluorescent dye for each sample, markers for each can be distinguished, like teams of runners wearing different-colored jerseys. For maximum efficiency, scientists can also set up groups of samples to run at slightly different times, like runners set off in a staggered start. CIMMYT will even be able to develop a new type of marker, known as SNPs, which allow numerous traits to be tested simultaneously, providing more information per sample.

All of this means that the new machines have a much higher throughput capacity, and can process many more samples for the same labor input, drastically reducing the per-sample cost—currently the major constraint on use of MAS. “If MAS were significantly cheaper, I would certainly use it in maize breeding,” says Atlin. “Effectively, it lets you quickly transfer the genes you want into improved varieties. If you’re doing a backcross between a donor with a desired trait and an improved parent with good agronomic performance, you’re trying to select for one characteristic from the donor, but against all its other genes. With a number of markers, MAS makes it possible to determine exactly which progeny combine the desired gene from the donor with the good genes from the other parent. You can get results in two generations, compared to four or five normally.”

The challenge for MAS is finding genes with substantial effects, especially for complex traits such as drought tolerance in maize. Atlin believes such genes are still to be found. “In the past, donors with a single useful gene or trait but otherwise poor agronomic qualities were very difficult to use in breeding, as they introduced so much bad material. We can get rid of that useless material through MAS. That opens up the field to look for useful genes in a wider range of parents. And genotyping technology is getting cheaper and better at finding genes all the time.”

In wheat, the hunt for useful markers at CIMMYT is more advanced. “We’re working with new markers to select for nematode resistance, leaf and stem rust resistance, boron tolerance, Fusarium resistance, and grain quality,” says Susanne Dreisigacker, CIMMYT wheat molecular biologist. “Our current work is all gel-based, which means running tests sample by sample and marker by marker. Being able to run many samples at the same time will make a huge difference.”

For more information: Marilyn Warburton, molecular geneticist (m.warburton@cgiar.org)

A quiet revolution is taking place in CIMMYT’s biotechnology labs. The team has just received a new generation of genotyping machines. These semi-automated work-horses will make it much easier to determine whether breeding lines contain specific useful genes. It is hoped that this will help maize and wheat breeders—through a process known as marker-assisted selection (MAS)—to make breeding more effective and get crop varieties with valuable traits to poor farmers more quickly.

A quiet revolution is taking place in CIMMYT’s biotechnology labs. The team has just received a new generation of genotyping machines. These semi-automated work-horses will make it much easier to determine whether breeding lines contain specific useful genes. It is hoped that this will help maize and wheat breeders—through a process known as marker-assisted selection (MAS)—to make breeding more effective and get crop varieties with valuable traits to poor farmers more quickly. The two ABI 3700 machines have been generously donated to CIMMYT by DuPont through its Pioneer Hi-Bred seed business, reflecting a fruitful collaborative relationship of more than a decade’s standing. Until now, CIMMYT has run most of its marker-assisted selection work on manual, gel-based electrophoresis apparatuses. In addition, analyses of genetic relationships between different wheat or maize lines have been run on older ABI genotyping machines, including two based on the previous, much slower generation of gel-based machines. The new machines can handle many more samples—96 each at a time—but it’s the savings in hands-on time that makes the real difference. “There’s no comparison,” says Marilyn Warburton, Head of CIMMYT’s Applied Biotechnology Center. “It will take us ten minutes to load one of these new machines, whereas it takes about four hours to make and load a manual electrophoresis gel.”

The two ABI 3700 machines have been generously donated to CIMMYT by DuPont through its Pioneer Hi-Bred seed business, reflecting a fruitful collaborative relationship of more than a decade’s standing. Until now, CIMMYT has run most of its marker-assisted selection work on manual, gel-based electrophoresis apparatuses. In addition, analyses of genetic relationships between different wheat or maize lines have been run on older ABI genotyping machines, including two based on the previous, much slower generation of gel-based machines. The new machines can handle many more samples—96 each at a time—but it’s the savings in hands-on time that makes the real difference. “There’s no comparison,” says Marilyn Warburton, Head of CIMMYT’s Applied Biotechnology Center. “It will take us ten minutes to load one of these new machines, whereas it takes about four hours to make and load a manual electrophoresis gel.” At an agricultural research station in Kenya, ingenuity, improvised tools, and a small group of talented, dedicated researchers and technicians using good science, are on the front line of the battle to prevent a potential multi-billion dollar crop disaster for the world.

At an agricultural research station in Kenya, ingenuity, improvised tools, and a small group of talented, dedicated researchers and technicians using good science, are on the front line of the battle to prevent a potential multi-billion dollar crop disaster for the world.

Improved maize makes a big difference in the lives of smallholder farmers on the slopes of Mt Kenya.

Improved maize makes a big difference in the lives of smallholder farmers on the slopes of Mt Kenya.

Kenya broke historic agricultural ground in a protected field on May 27 when it sowed its first transgenic maize seeds into local soil. Supported by the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture and the Rockefeller Foundation, this experiment is the first of its kind in the region. The Bt maize plants that sprout will be resistant to stem borer, an insect that drills into the maize stalk and causes significant losses to Kenyan harvests.

Kenya broke historic agricultural ground in a protected field on May 27 when it sowed its first transgenic maize seeds into local soil. Supported by the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture and the Rockefeller Foundation, this experiment is the first of its kind in the region. The Bt maize plants that sprout will be resistant to stem borer, an insect that drills into the maize stalk and causes significant losses to Kenyan harvests.

Techniques from maize may make better wheats.

Techniques from maize may make better wheats.

Visiting family farms in Punjab this month, US Ambassador to India Dr. David C. Mulford learned how conservation agriculture benefits farmers and the local economy.

Visiting family farms in Punjab this month, US Ambassador to India Dr. David C. Mulford learned how conservation agriculture benefits farmers and the local economy. Ambassador Mulford and others at the field visit discussed some of the challenges and concerns shared by farmers and researchers, such as the need for appropriate field equipment for conservation agriculture, the effects on local labor markets, the role of equipment manufacturers, and the need to cope with large amounts of crop residue without plowing and burning. Despite the challenges, the projected benefits of conservation agriculture are promising. In 2002, researchers at Australia’s Centre for International Economics calculated that the increased use of zero-tillage techniques promoted by the Rice-Wheat Consortium offered a gain of 1.8 million Australian dollars per year to the Indian economy.

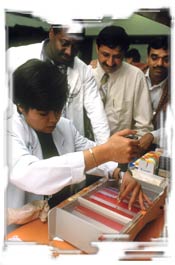

Ambassador Mulford and others at the field visit discussed some of the challenges and concerns shared by farmers and researchers, such as the need for appropriate field equipment for conservation agriculture, the effects on local labor markets, the role of equipment manufacturers, and the need to cope with large amounts of crop residue without plowing and burning. Despite the challenges, the projected benefits of conservation agriculture are promising. In 2002, researchers at Australia’s Centre for International Economics calculated that the increased use of zero-tillage techniques promoted by the Rice-Wheat Consortium offered a gain of 1.8 million Australian dollars per year to the Indian economy. CIMMYT maize breeders Dave Beck and Hugo Cordova organized and led a seed production course on 6-14 September at CIMMYT headquarters in El Batan, Mexico. The course, entitled “Production of High Quality Seed with an Emphasis on Quality Protein Maize,” was funded in part by the Mexican national organization SAGARPA.

CIMMYT maize breeders Dave Beck and Hugo Cordova organized and led a seed production course on 6-14 September at CIMMYT headquarters in El Batan, Mexico. The course, entitled “Production of High Quality Seed with an Emphasis on Quality Protein Maize,” was funded in part by the Mexican national organization SAGARPA.

A USAID-funded study by Rutgers economist Carl Pray concludes that present and future impacts of the Asian Maize Biotechnology Network (AMBIONET)—a forum that during 1998-2005 fostered the use of biotechnology to boost maize yields in Asia’s developing countries—should produce benefits that far exceed its cost.

A USAID-funded study by Rutgers economist Carl Pray concludes that present and future impacts of the Asian Maize Biotechnology Network (AMBIONET)—a forum that during 1998-2005 fostered the use of biotechnology to boost maize yields in Asia’s developing countries—should produce benefits that far exceed its cost. Zero-tillage trials in rainfed, winter wheat-fallow systems show smallholder farmers on the Anatolian Plains a way to double their harvests.

Zero-tillage trials in rainfed, winter wheat-fallow systems show smallholder farmers on the Anatolian Plains a way to double their harvests.

Retired agronomist Mufit Kalayci, recently brought back to the Anatolian Agricultural Research Center in Eskisiher, Turkey, to mentor a new team, sees the value of zero-tillage in intensive, irrigated systems with more than a single crop per year, but is skeptical about using it with traditional rainfed wheat farms. “I don’t think you can retain enough moisture over the fallow period.” he says. For that reason, one of the goals of the zero-tillage experiment was to see if a second crop other than weeds could be grown during the fallow season. This question will be answered in coming years.

Retired agronomist Mufit Kalayci, recently brought back to the Anatolian Agricultural Research Center in Eskisiher, Turkey, to mentor a new team, sees the value of zero-tillage in intensive, irrigated systems with more than a single crop per year, but is skeptical about using it with traditional rainfed wheat farms. “I don’t think you can retain enough moisture over the fallow period.” he says. For that reason, one of the goals of the zero-tillage experiment was to see if a second crop other than weeds could be grown during the fallow season. This question will be answered in coming years. Farmers and community leaders in Kenya’s most densely-populated region have organized to produce and sell seed of a maize variety so well-suited for smallholders that distant peers in highland Nepal have also selected it.

Farmers and community leaders in Kenya’s most densely-populated region have organized to produce and sell seed of a maize variety so well-suited for smallholders that distant peers in highland Nepal have also selected it.