Earliest Mexican wheats supply latest useful traits

CIMMYT E-News, vol 5 no. 6, June 2008

Centuries ago, Spanish monks brought wheat to Mexico to use in Roman Catholic religious ceremonies. The genetic heritage of some of these “sacramental wheats” lives on in farmers’ fields. CIMMYT researchers have led the way in collecting and characterizing these first wheats, preserving their biodiversity and using them as sources of traits like disease resistance and drought tolerance.

Centuries ago, Spanish monks brought wheat to Mexico to use in Roman Catholic religious ceremonies. The genetic heritage of some of these “sacramental wheats” lives on in farmers’ fields. CIMMYT researchers have led the way in collecting and characterizing these first wheats, preserving their biodiversity and using them as sources of traits like disease resistance and drought tolerance.

“I’d say to Bent: ‘Let’s look for the cemetery,’ ” recalls Julio Huerta, CIMMYT wheat pathologist, of his trips to villages in Mexico with his late colleague Bent Skovmand, CIMMYT wheat genetic resource expert. “And the sacramental wheats would be there, sometimes hundreds of types.”

The first wheat was brought to Mexico in 1523 around the area now occupied by Mexico City. The crop soon spread outside the central plateau with the help of Catholic monks: it traveled to the state of Michoacán in the 1530s with the Franciscans, while the Dominicans took wheat to the state of Oaxaca in 1540 and gave grains to the native inhabitants to produce flour for unleavened bread used during Roman Catholic religious ceremonies. “Still today, many church ornaments in Michoacán have wheat straw in them,” says Huerta.

Huerta and Skovmand went on sacramental wheat-gathering expeditions in 19 Mexican states. “Many people thought we were just collecting trash,” he says. “But we wanted to collect sacramental wheats before they disappeared. I’m not that surprised that some have very valuable attributes for breeding programs.”

Farmers in Mexico and elsewhere face water shortages and rising temperatures due to climate change. CIMMYT scientists are looking to sacramental wheats as one source of drought-tolerance. Field trials at the center’s Cuidad Obregón wheat research facility show some sacramental wheats have better early ground cover, quickly covering the soil and safeguarding moisture from evaporating. Others have enhanced levels of soluble stem carbohydrates which help fill the wheat grain even under drought, while some show better water uptake in deep soils thanks to their deep roots.

As farmers gain access to improved varieties or migrate to cities, sacramental wheats are disappearing from fields. With the hope of conserving these rare and valuable varieties, Huerta and Skovmand started collecting them in 1992, collaborating with the Mexican National Institute for Forestry, Agriculture, and Livestock Research (INIFAP) and supported by the Mexican Organization for the Study of Biodiversity (CONABIO). Their efforts were not in vain—10,000 samples from 249 sites in Mexico were added to the CIMMYT germplasm bank, and duplicate samples deposited in the INIFAP germplasm bank.

Only the strongest survive

The deep volcanic soils of Los Altos de Mixteca, Oaxaca, and the dry conditions in some parts of Mexico were not ideal for growing wheat. “If the wheats didn’t have deep roots and it didn’t rain, they were dead,” says CIMMYT wheat physiologist, Matthew Reynolds. The wheat genotypes that survived for centuries were perhaps the ones with drought-tolerance traits for which farmers selected. “Say the farmer had a mixture of sacramental wheats that looked reasonably similar—similar enough that he could manage them but diverse enough to adapt to local conditions,” explains Reynolds. “One year certain lines would do better than others and the farmer might harvest just the best-looking plants to sow the next year.”

Sacramental wheats often grew in isolated rural areas, meaning that some never crossed with other varieties, leaving their genetic heritage intact. They are often tall and closely adapted to local conditions, according to Huerta, and farmers who still grow them say they taste better than modern varieties.

Reynolds is combining the old and the new—crossing improved modern cultivars with sacramental wheats to obtain their drought-tolerance attributes. “We now have several lines that are candidates for international nurseries,” he says. “They’ll go to South Asia and North Africa, and will be especially useful for regions with deep soils and residual moisture.”

Old wheats come back in style

In 2001, a new leaf rust race appeared on Altar 84, the most widely-grown wheat cultivar in Sonora State, Mexico. The CIMMYT wheat genetic resources program immediately looked for sources of resistance in the germplasm bank. The durum collection of sacramental wheats from Oaxaca, Mexico, proved extremely useful: all but one displayed minor gene or major gene resistance to the new leaf rust race, confirming that sacramental wheats are a valuable breeding resource.

CIMMYT researchers are still unlocking the potential of sacramental wheats. “We started to characterize them for resistance to leaf and yellow rust, and the collections from the state of Mexico for wheat head scab and Septoria,” says Huerta. We were surprised to find many, many resistant lines. “But until we finish characterizing all of them, we won’t know what else is there.”

For more information on sacramental wheats: Julio Huerta, wheat pathologist (j.huerta@cgiar.org) or Matthew Reynolds, wheat physiologist, ( m.reynolds@cgiar.org).

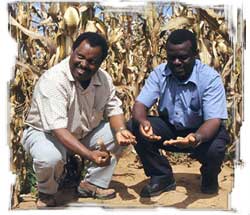

CIMMYT’s partnerships on maize in eastern Africa hark back to the 1960s, when the center was launched. Formal networking since that time with researchers and extension workers, policy makers, non-government organizations, seed companies, millers, and farmers have culminated in successful breeding and dissemination teams and promising new varieties rated highly by farmers. Awards to teams in Tanzania and Ethiopia recently highlighted the value of these partnerships.

CIMMYT’s partnerships on maize in eastern Africa hark back to the 1960s, when the center was launched. Formal networking since that time with researchers and extension workers, policy makers, non-government organizations, seed companies, millers, and farmers have culminated in successful breeding and dissemination teams and promising new varieties rated highly by farmers. Awards to teams in Tanzania and Ethiopia recently highlighted the value of these partnerships. Some of the poorest and most disadvantaged wheat farmers live in areas with less than 350 mm annual rainfall and their livelihoods often depend solely on income from wheat production. Moreover, in these areas wheat is a staple food, providing around half the daily caloric requirement, and also constitutes an important source of fodder for livestock.

Some of the poorest and most disadvantaged wheat farmers live in areas with less than 350 mm annual rainfall and their livelihoods often depend solely on income from wheat production. Moreover, in these areas wheat is a staple food, providing around half the daily caloric requirement, and also constitutes an important source of fodder for livestock. Farmers of the village of Kathaka Kaome in Embu district near Mount Kenya are saying that quality protein maize (QPM) is as nutritious as Githeri—a local dish made from maize and beans.

Farmers of the village of Kathaka Kaome in Embu district near Mount Kenya are saying that quality protein maize (QPM) is as nutritious as Githeri—a local dish made from maize and beans.

A CIMMYT research team is using an old but effective technique to get a head start on some very advanced crop science. Their aim is to breed high yielding maize that also resists infection by a dangerous fungus. As part of a USAID-funded project, the team uses ultraviolet or black light to identify maize that inhibits Aspergillus flavus, a fungus that produces potent toxins known as aflatoxins.

A CIMMYT research team is using an old but effective technique to get a head start on some very advanced crop science. Their aim is to breed high yielding maize that also resists infection by a dangerous fungus. As part of a USAID-funded project, the team uses ultraviolet or black light to identify maize that inhibits Aspergillus flavus, a fungus that produces potent toxins known as aflatoxins. Farmers seal the corn earworm’s fate in Peru with an oily approach.

Farmers seal the corn earworm’s fate in Peru with an oily approach.

New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance.

New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance.

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

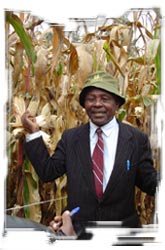

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Paul Mapfumo throws his fist into the air and intones, “”Pamberi ne kurima! Pasi neNzara!” Shona for “Forward with agriculture! Down with hunger!” This is the greeting every speaker uses before addressing the gathering of farmers attending a field day in Rusape settlement, eastern Zimbabwe. The 40-odd farmers, young and old, men and women, are united in their desire to learn of ways to rebuild the fertility of their farms’ soils, for better maize harvests. And Mapfumo, the newly appointed coordinator, and members of the Soil Fertility Consortium for Southern Africa (SOFECSA) such as CIMMYT, are determined to help them do just that.

Paul Mapfumo throws his fist into the air and intones, “”Pamberi ne kurima! Pasi neNzara!” Shona for “Forward with agriculture! Down with hunger!” This is the greeting every speaker uses before addressing the gathering of farmers attending a field day in Rusape settlement, eastern Zimbabwe. The 40-odd farmers, young and old, men and women, are united in their desire to learn of ways to rebuild the fertility of their farms’ soils, for better maize harvests. And Mapfumo, the newly appointed coordinator, and members of the Soil Fertility Consortium for Southern Africa (SOFECSA) such as CIMMYT, are determined to help them do just that.

As the price of wheat goes up, countries such as the Republic of Mauritius are feeling the pinch. A former British colony off the coast of Madagascar, it imports most of its wheat from France and Australia. But with help from CIMMYT, the island has started trials to grow its own wheat—and results to date look promising.

As the price of wheat goes up, countries such as the Republic of Mauritius are feeling the pinch. A former British colony off the coast of Madagascar, it imports most of its wheat from France and Australia. But with help from CIMMYT, the island has started trials to grow its own wheat—and results to date look promising.

Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums.

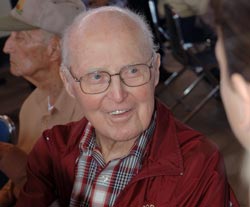

Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums. Borlaug, still a consultant with CIMMYT, is also the President of the Sasakawa Africa Association, which is devoted to improving the lives of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa. One of his reasons for visiting Obregón this time was to see and learn about a technology developed by Oklahoma State University (OSU) and CIMMYT. The approach allows farmers easily and cheaply to determine the optimum application of fertilizer for a developing wheat or maize crop. Fertilizer resources are scarce in much of Africa, so timely application of the correct amounts can save farmers money and help produce a better crop.

Borlaug, still a consultant with CIMMYT, is also the President of the Sasakawa Africa Association, which is devoted to improving the lives of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa. One of his reasons for visiting Obregón this time was to see and learn about a technology developed by Oklahoma State University (OSU) and CIMMYT. The approach allows farmers easily and cheaply to determine the optimum application of fertilizer for a developing wheat or maize crop. Fertilizer resources are scarce in much of Africa, so timely application of the correct amounts can save farmers money and help produce a better crop.