Brothers on the land

CIMMYT E-News, vol 4 no. 7, July 2007

Somewhere between the romance of the Silk Road and the land mines, CIMMYT works as part of the team that is rebuilding the shattered agriculture of Afghanistan.

It looked like a scene from a Tolstoy novel—four, weathered men with hand sickles working under the blazing, noonday sun to harvest a field of wheat. No combine harvester here, just the power of their backs and arms and hands. But Tolstoy wrote 140 years ago. This scene is today, 2007, in northern Afghanistan near the city of Mazur i Sharif, not far from the Uzbekistan border. Wheat is the most important food crop in this embattled country where 85% of the population depends on agriculture to sustain life. Yet wheat yields on its worn soils are notoriously low—only 2-2.5 tons per hectare, even on irrigated land. Unlike the republics of the former Soviet Union to the north, land holdings in this part of Afghanistan are small and do not lend themselves to large scale mechanization. You can understand what that really means when you talk to the farmers themselves.

Faizal Ahmad and his brother Hayatt Mohammad are sharecroppers on this 8 hectare parcel of land. They pay the landowner a share and the crew that is harvesting gets a share, and with what is left, they try to feed their families, maybe sell a little.

Faizal Ahmad and his brother Hayatt Mohammad are sharecroppers on this 8 hectare parcel of land. They pay the landowner a share and the crew that is harvesting gets a share, and with what is left, they try to feed their families, maybe sell a little.

“From the sharecropping we just survive,” Faizal says. “We are not going to get rich and we won’t make very much money.”

The crew working the field is part of a community harvesting system. They are paid in wheat seed rather than cash and get two meals for the day’s work. They too keep some land for wheat. In Afghanistan, no matter what else you grow, wheat comes first for family food security.

During the Taliban and warlord times, the brothers fled with their families to Pakistan but returned with the installation of the new government in 2004. And even though farming this irrigated land year round is tough, Hayatt, who is married with a son and daughter, says they are making a go of it. “Life is difficult, and we are struggling and hope things could improve.”

They are growing an improved but older wheat variety called Zardana Kunduzi which they get through an informal farmer-to-farmer seed system. Unhappily, their land is infested with wild oats. The weed reduces the wheat harvest, both by competing for space and by taking nutrients. No matter what the farmers try, the weeds come back every season. Of course herbicides are not an option for people with so little.

This is the milieu in which CIMMYT finds itself in Afghanistan—older varieties that are more susceptible to pests and diseases, a seed system that needs rebuilding from the ground up and agronomic practices that need improvement to give farmers like Faizal and Hayatt a real chance on the little land they have.

In partnership with the Ministry of Agriculture Irrigation and Livestock of Afghanistan (MAIL), CIMMYT has been testing potentially better wheats for conditions specific to different parts of the country. Already a new variety of durum wheat is available and not far from where Faizel, Hayatt and the crew are working another farmer is growing the durum for seed. His field is healthy and the crop looks excellent. He has been contracted by one of the new seed production companies that are part of a project sponsored by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Making that seed system sustainable, while providing seed at an affordable price is a great challenge.

The new agriculture master plan for Afghanistan prepared by MAIL praises CIMMYT for “considerable training of Afghans (that) sets a desirable standard.” In fact more than 50 Afghan researchers have had training at CIMMYT and more than 70 technicians, farmers and NGO workers have taken technical training at workshops in Afghanistan. Much of CIMMYT’s work in Afghanistan is supported by Australia through both the Australian overseas aid program, AusAID and the Australian Council for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR).

At least three more varieties developed from materials originally from CIMMYT (some via the winter wheat breeding program in Turkey) are in the new varietal release pipeline that Afghanistan has implemented. They have already demonstrated in farmers’ fields that they are well-suited to local conditions and can provide more wheat per hectare than farmers currently harvest with yields in on-farm trials of almost 5 tons per hectare, double what most farmers get. These wheats can be seen in trials at the Dehdadi Research Farm near Mazur, almost within sight of the sharecropping brothers.

At least three more varieties developed from materials originally from CIMMYT (some via the winter wheat breeding program in Turkey) are in the new varietal release pipeline that Afghanistan has implemented. They have already demonstrated in farmers’ fields that they are well-suited to local conditions and can provide more wheat per hectare than farmers currently harvest with yields in on-farm trials of almost 5 tons per hectare, double what most farmers get. These wheats can be seen in trials at the Dehdadi Research Farm near Mazur, almost within sight of the sharecropping brothers.

Nevertheless, Mahmoud Osmanzai, the CIMMYT country coordinator in Afghanistan says there are still real challenges to close the gap between the yields that can be achieved in well-managed demonstration plots and the yields poor sharecroppers like Faizel and Hayatt actually achieve. “We have good varieties that will make good bread,” he says. “Now we have to find a way that let’s resource-poor farmers get the most from them.”

For the sharecropping brothers, a little more income from their small piece of borrowed land could go a long way. “Yes if we could save, we could have a second business.” says Faizal. “We would probably get a shop as well or buy a car, run a taxi, build something to produce more.”

For more information: Mahmood Osmanzai, Afghanistan country coordinator (m.osmanzai@cgiar.org)

CIMMYT’s biometrics team receives special recognition for advancing the science behind crop genetic resource conservation.

CIMMYT’s biometrics team receives special recognition for advancing the science behind crop genetic resource conservation.

Wheat lines that resisted virulent stem rust last season have now succumbed.

Wheat lines that resisted virulent stem rust last season have now succumbed.

A new study from the Carnegie Institute of Washington, Stanford University, and CIMMYT shows wheat yield gains in northern Mexico could be due mostly to the weather.

A new study from the Carnegie Institute of Washington, Stanford University, and CIMMYT shows wheat yield gains in northern Mexico could be due mostly to the weather.

In the next 25 years, a very large share of the additional wheat needed to feed the rising population in developing countries will come from intensive farming systems. It is more important than ever to learn how to reduce the impact of intensive agriculture on the environment while ensuring that those systems can supply much-needed food in the years to come.

In the next 25 years, a very large share of the additional wheat needed to feed the rising population in developing countries will come from intensive farming systems. It is more important than ever to learn how to reduce the impact of intensive agriculture on the environment while ensuring that those systems can supply much-needed food in the years to come. To get the ball rolling, five scientists were designated to attend an intensive two-week course on regulatory issues and processes, conducted in August at Ghent University, Belgium. The scientists were involved in either IRMA II or regulatory processes: A. Pellegrineschi and S. Mugo (CIMMYT), M. Mulaa and S. Gichuki (KARI), and R. Onamu (KEPHIS). On the heels of the regulatory workshop, a two-day workshop to develop, plan and incorporate regulatory activities in the IRMA II project plan was held in Nairobi in September 2004. Twenty-one participants from seven institutions attended the workshop: KARI, CIMMYT, KEPHIS, National Council for Science and Technology (NCST), Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF), and International Biotech Regulatory Services. The objectives of the meeting were to (1) update the status of Bt maize in IRMA project; (2) identify information needed for a dossier on Bt genes to be deployed by the project;(3) determine sources of the needed information and identify gaps to be filled through research; (4) determine activities needed to fill the gaps, including resources and assigning responsibilities; and (5) update the IRMA II project plan, specifically on regulatory issues. After agreeing on the components of a regulatory package, the team split up into working groups and identified the required information, and developed activities over time, including budgets and responsibilities. Subsequently, a small task group incorporated the regulatory strategies into the project plan and created a revised structure for IRMA II. Ten themes were recommended:

To get the ball rolling, five scientists were designated to attend an intensive two-week course on regulatory issues and processes, conducted in August at Ghent University, Belgium. The scientists were involved in either IRMA II or regulatory processes: A. Pellegrineschi and S. Mugo (CIMMYT), M. Mulaa and S. Gichuki (KARI), and R. Onamu (KEPHIS). On the heels of the regulatory workshop, a two-day workshop to develop, plan and incorporate regulatory activities in the IRMA II project plan was held in Nairobi in September 2004. Twenty-one participants from seven institutions attended the workshop: KARI, CIMMYT, KEPHIS, National Council for Science and Technology (NCST), Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF), and International Biotech Regulatory Services. The objectives of the meeting were to (1) update the status of Bt maize in IRMA project; (2) identify information needed for a dossier on Bt genes to be deployed by the project;(3) determine sources of the needed information and identify gaps to be filled through research; (4) determine activities needed to fill the gaps, including resources and assigning responsibilities; and (5) update the IRMA II project plan, specifically on regulatory issues. After agreeing on the components of a regulatory package, the team split up into working groups and identified the required information, and developed activities over time, including budgets and responsibilities. Subsequently, a small task group incorporated the regulatory strategies into the project plan and created a revised structure for IRMA II. Ten themes were recommended: In a determined effort to shield consumers against food price volatility, the government of Ecuador has renewed its investment in food crop research, including a vigorous program to restore wheat production and reduce the nation’s perilous dependence on imported grain.

In a determined effort to shield consumers against food price volatility, the government of Ecuador has renewed its investment in food crop research, including a vigorous program to restore wheat production and reduce the nation’s perilous dependence on imported grain. A posthumous tribute

A posthumous tribute

After decades of stability, world food prices jumped more than 80% in 2008. Recent good harvests have brought prices down, but not to previous, historically-low levels, and most economists expect food costs to remain at much higher levels than before. At any moment catastrophic events like a drought or major crop disease outbreak could shock fragile grain markets and quickly send values skyrocketing anew.

After decades of stability, world food prices jumped more than 80% in 2008. Recent good harvests have brought prices down, but not to previous, historically-low levels, and most economists expect food costs to remain at much higher levels than before. At any moment catastrophic events like a drought or major crop disease outbreak could shock fragile grain markets and quickly send values skyrocketing anew. Work by CIMMYT with researchers, extension workers, policymakers, and farmers in Bangladesh for nearly four decades has helped establish wheat and maize among the country’s major cereal crops, made farming systems more productive and sustainable, improved food security and livelihoods, and won ringing praise from national decision makers in agriculture, according to a recent report published by CIMMYT.

Work by CIMMYT with researchers, extension workers, policymakers, and farmers in Bangladesh for nearly four decades has helped establish wheat and maize among the country’s major cereal crops, made farming systems more productive and sustainable, improved food security and livelihoods, and won ringing praise from national decision makers in agriculture, according to a recent report published by CIMMYT.

Erginbas is just beginning work on a project to screen wheat for resistance to a disease called crown rot. It is caused by a microscopic fungus in the soil called Fusarium culmorum (related to but not the same as the Fusarium fungus that causes head blight in wheat) and can cause farmers serious loss of yield. Her first tests have been with plants grown in a greenhouse on the station. Later she will expand her work to the field and as part of her program will spend some time in Australia with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO). Since there is some evidence that the fungus that causes crown rot can survive for up to two years in crop residues, there is a great interest in this work as more farmers adopt reduced tillage and stubble retention on their land.

Erginbas is just beginning work on a project to screen wheat for resistance to a disease called crown rot. It is caused by a microscopic fungus in the soil called Fusarium culmorum (related to but not the same as the Fusarium fungus that causes head blight in wheat) and can cause farmers serious loss of yield. Her first tests have been with plants grown in a greenhouse on the station. Later she will expand her work to the field and as part of her program will spend some time in Australia with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO). Since there is some evidence that the fungus that causes crown rot can survive for up to two years in crop residues, there is a great interest in this work as more farmers adopt reduced tillage and stubble retention on their land. These pathogens are especially damaging when wheat is grown under more marginal conditions, and so the work in Turkey that these two young students are doing may have its greatest impact where farmers struggle the most.

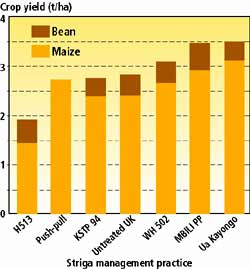

These pathogens are especially damaging when wheat is grown under more marginal conditions, and so the work in Turkey that these two young students are doing may have its greatest impact where farmers struggle the most. Kenyan farmers’ verdict is out: “Ua Kayongo is the best Striga control practice and we will adopt it.”

Kenyan farmers’ verdict is out: “Ua Kayongo is the best Striga control practice and we will adopt it.” Farmers in the WeRATE evaluations were able to plant the new maize using their normal husbandry methods, including intercropping with legumes and root crops. “I’ve been pulling and burying Striga on my 5-acre farm for the past 17 years and the problem has only grown worse,” said Rose Katete, a farmer from Teso; “Ua Kayongo has provided the best crop of maize that I’ve ever grown!”

Farmers in the WeRATE evaluations were able to plant the new maize using their normal husbandry methods, including intercropping with legumes and root crops. “I’ve been pulling and burying Striga on my 5-acre farm for the past 17 years and the problem has only grown worse,” said Rose Katete, a farmer from Teso; “Ua Kayongo has provided the best crop of maize that I’ve ever grown!” In recent years, CIMMYT’s collaboration with partners in the South Africa Development Community (SADC) has flourished in scope and strength to span research, training, and shared experiences with researchers, extension workers, farmers, seed companies, and four national universities. The various parties bring their strengths to this alliance, resulting in synergy and a fluid transfer of impact-oriented technologies and knowledge to smallholder farmers.

In recent years, CIMMYT’s collaboration with partners in the South Africa Development Community (SADC) has flourished in scope and strength to span research, training, and shared experiences with researchers, extension workers, farmers, seed companies, and four national universities. The various parties bring their strengths to this alliance, resulting in synergy and a fluid transfer of impact-oriented technologies and knowledge to smallholder farmers. Farmers in northern Bangladesh are making money off maize thanks to training and support from CIMMYT and partners. A relatively new crop in Bangladesh, maize has been mostly grown for the poultry feed industry. But now agricultural entrepreneurs want to promote the crop for human consumption and farmers are starting to eat some of the maize they grow.

Farmers in northern Bangladesh are making money off maize thanks to training and support from CIMMYT and partners. A relatively new crop in Bangladesh, maize has been mostly grown for the poultry feed industry. But now agricultural entrepreneurs want to promote the crop for human consumption and farmers are starting to eat some of the maize they grow.