CIMMYT–China Wheat Quality Conference Highlights 10 Years of Collaboration

June, 2004

Which food crop is traded in larger quantities than any other in the world? The answer is wheat, and China produces more of it than any other country. With more than 150 participants from 20 countries in attendance, CIMMYT and China held their first joint wheat quality conference in Beijing from 29 to 31 May. The conference focused on progress in China’s wheat quality research, educated participants about quality needs of the milling industry and consumers, and promoted international collaboration.

In recent years, advanced science has been making wheat more nutritious, easy to process, and profitable. Scientists can improve quality characteristics such as grain hardness, protein content, gluten strength, color, and dough processing properties. Quality improvement, however, is not an objective, one-wheat-fits-all-purposes kind of business. Wheat end products vary by region and require grain with different characteristics. For example, 80% of wheat in China is used for noodles and dumplings, but the desired wheat quality for those products might not be appropriate for pasta in Italy or couscous in North Africa.

“You can see a wide variation of wheat use reflecting cultural influences over many centuries,” says CIMMYT Director General Masa Iwanaga, who gave a keynote presentation at the conference about the benefits of adding value to wheat to improve the livelihoods of poor people. Iwanaga says he is impressed by China’s wheat quality research and emphasis on biotechnology in recent years.

Participants from major wheat producing regions such as China, Central Asia, India, the European Union, Eastern Europe, the United States, and Australia presented updates on a variety of topics related to the global wheat industry and quality management. The participants included experts in genomics, breeding, crop management, cereal chemistry, and the milling industry, among others.

The US, Australia, Canada, and the EU see Asia as a good market for their wheat, says Javier Peña, head of industrial quality at CIMMYT. Asian foods such as noodles have been becoming more popular in the west, says Peña, while traditional western wheat-based foods have been gaining popularity in Asia. The milling industry has been growing to meet this increasing demand. “It was evident that globalization is influencing consumers’ preferences,” he says.

Conference participant and CIMMYT wheat breeder Morten Lillemo thinks the organizers did a good job assembling top lecturers to provide information. Chinese wheat breeders have been paying a lot of attention to improving quality, he says, and participants now understand the characteristics that traditional Chinese end products require.

“China is the largest wheat producer in the world, but the quality of their wheat is highly variable, even for traditional products like steamed bread and noodles,” says Lillemo. “For me it was most interesting to learn about the wheat quality work going on in China, which challenges they have, and how they are dealing with them.”

The 10-year-long CIMMYT–China collaboration has been fruitful. Chinese wheat has been used to develop new varieties with Fusarium and Karnal bunt disease resistance, high yield potential, and agronomic traits such as lodging resistance and rapid grain filling. In turn, CIMMYT has helped to improve the productivity, disease resistance, and processing quality of Chinese wheats. It has also developed human resources and helped build research infrastructure.

“The progress China has made in this period has been impressive in the areas of molecular biology, breeding, and food processing,” says Peña, who thought the conference covered a good balance of topics, ranging from genetics to consumer preferences. “The government is really supporting the research. They have new buildings and modern equipment for molecular biology and wheat quality testing.”

The Quality and Training Complex sponsored by the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and CIMMYT is a new effort. It offers a testing system for various wheat-based foods, facilities for genetic studies and other research using molecular markers, and training for graduates, postdoctoral fellows, and visiting scientists.

Along with improved wheat and better cropping practices that help farmers save money on costly inputs, such as water, Iwanaga believes that more marketable maize and wheat grain will be important for improving the profitability of maize and wheat production in developing countries. He would like to increase the benefits that farmers reap from their harvests by bettering a range of traits, including taste, texture, safety, and nutrition with added protein or vitamins. That way, farmers can earn more money from better quality wheat.

Conference presentations covered a wide range of topics: molecular studies of the evolution of the wheat genome; new tools to assess heat tolerance and grain quality in wheat genotypes; molecular genetic modification of wheat flour quality; the biochemical and molecular genetic study of glutenin proteins in bread wheat and related species; the molecular investigation of storage product accumulation in wheat endosperm; molecular and conventional methods for assessing the processing quality of Chinese wheat; challenges for breeding high-quality wheat with high yield potential; the impact of genetic resources on breeding for breadmaking quality in common wheat; wheat quality improvement by genetic manipulation and biosafety assessment of transgenic wheat lines; and quality characteristics of transgenic wheat lines.

The conference was organized by the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences / National Wheat Improvement Center, the Chinese Academy of Science, CIMMYT, BRI Australia, Limagrain, and the Crop Science Society of China. It was sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Agriculture, the National Nature Science Foundation of China, the Grains Research and Development Corporation, and Japan International Cooperation Agency.

For information: Zonghu He

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Paul Mapfumo throws his fist into the air and intones, “”Pamberi ne kurima! Pasi neNzara!” Shona for “Forward with agriculture! Down with hunger!” This is the greeting every speaker uses before addressing the gathering of farmers attending a field day in Rusape settlement, eastern Zimbabwe. The 40-odd farmers, young and old, men and women, are united in their desire to learn of ways to rebuild the fertility of their farms’ soils, for better maize harvests. And Mapfumo, the newly appointed coordinator, and members of the Soil Fertility Consortium for Southern Africa (SOFECSA) such as CIMMYT, are determined to help them do just that.

Paul Mapfumo throws his fist into the air and intones, “”Pamberi ne kurima! Pasi neNzara!” Shona for “Forward with agriculture! Down with hunger!” This is the greeting every speaker uses before addressing the gathering of farmers attending a field day in Rusape settlement, eastern Zimbabwe. The 40-odd farmers, young and old, men and women, are united in their desire to learn of ways to rebuild the fertility of their farms’ soils, for better maize harvests. And Mapfumo, the newly appointed coordinator, and members of the Soil Fertility Consortium for Southern Africa (SOFECSA) such as CIMMYT, are determined to help them do just that.

As the price of wheat goes up, countries such as the Republic of Mauritius are feeling the pinch. A former British colony off the coast of Madagascar, it imports most of its wheat from France and Australia. But with help from CIMMYT, the island has started trials to grow its own wheat—and results to date look promising.

As the price of wheat goes up, countries such as the Republic of Mauritius are feeling the pinch. A former British colony off the coast of Madagascar, it imports most of its wheat from France and Australia. But with help from CIMMYT, the island has started trials to grow its own wheat—and results to date look promising.

Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums.

Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums. Borlaug, still a consultant with CIMMYT, is also the President of the Sasakawa Africa Association, which is devoted to improving the lives of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa. One of his reasons for visiting Obregón this time was to see and learn about a technology developed by Oklahoma State University (OSU) and CIMMYT. The approach allows farmers easily and cheaply to determine the optimum application of fertilizer for a developing wheat or maize crop. Fertilizer resources are scarce in much of Africa, so timely application of the correct amounts can save farmers money and help produce a better crop.

Borlaug, still a consultant with CIMMYT, is also the President of the Sasakawa Africa Association, which is devoted to improving the lives of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa. One of his reasons for visiting Obregón this time was to see and learn about a technology developed by Oklahoma State University (OSU) and CIMMYT. The approach allows farmers easily and cheaply to determine the optimum application of fertilizer for a developing wheat or maize crop. Fertilizer resources are scarce in much of Africa, so timely application of the correct amounts can save farmers money and help produce a better crop.

A radio program in Nepal brings information to farmers in a language they understand.

A radio program in Nepal brings information to farmers in a language they understand.

Experimental auctions in Kenya gauge farmer interest in vitamin A-enriched maize.

Experimental auctions in Kenya gauge farmer interest in vitamin A-enriched maize. Determining how consumers will balance their desire for nutritionally superior maize while sacrificing the color to which they are accustomed sheds light on whether or not biofortified maize will be readily adopted. “Despite a need for this knowledge, very few consumer studies of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa have been done,” says Hugo De Groote, CIMMYT economist.

Determining how consumers will balance their desire for nutritionally superior maize while sacrificing the color to which they are accustomed sheds light on whether or not biofortified maize will be readily adopted. “Despite a need for this knowledge, very few consumer studies of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa have been done,” says Hugo De Groote, CIMMYT economist. In 2009, out of a global population of 6.8 billion people, more than 1 billion regularly woke up and went to bed hungry. By 2050 the population is expected to grow to 9.1 billion people, most of whom will be in developing countries. Unless we can increase global food production by 70%, the number of chronically hungry will continue to swell. To help ensure global food security, a new research consortium aims to boost yields of wheat—a major staple food crop.

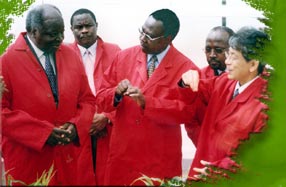

In 2009, out of a global population of 6.8 billion people, more than 1 billion regularly woke up and went to bed hungry. By 2050 the population is expected to grow to 9.1 billion people, most of whom will be in developing countries. Unless we can increase global food production by 70%, the number of chronically hungry will continue to swell. To help ensure global food security, a new research consortium aims to boost yields of wheat—a major staple food crop. The official opening on 23 June 2004 of a level-two biosafety greenhouse in Nairobi, Kenya was marked by happy fanfare, but more importantly, a serious commitment from the highest levels to use biotechnology to help solve Africa’s pressing agricultural problems.

The official opening on 23 June 2004 of a level-two biosafety greenhouse in Nairobi, Kenya was marked by happy fanfare, but more importantly, a serious commitment from the highest levels to use biotechnology to help solve Africa’s pressing agricultural problems. The President of Kenya, his Excellency the Hon. Mwai Kibaki, officially launched the facility. He was joined by Masa Iwanaga, CIMMYT’s Director General; Romano Kiome, Director of KARI; Andrew Bennett, Executive Director of the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, which provided funds for the new facility; Shivaji Pandey, Director of CIMMYT’s African Livelihoods Program (ALP); and the Hon. Kipruto Arap Kirwa, Minister of Agriculture.

The President of Kenya, his Excellency the Hon. Mwai Kibaki, officially launched the facility. He was joined by Masa Iwanaga, CIMMYT’s Director General; Romano Kiome, Director of KARI; Andrew Bennett, Executive Director of the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, which provided funds for the new facility; Shivaji Pandey, Director of CIMMYT’s African Livelihoods Program (ALP); and the Hon. Kipruto Arap Kirwa, Minister of Agriculture.

Global, collaborative wheat research brings enormous gains for developing country farmers, particularly in more marginal environments, according to an article in the Centenary Review of the Journal of Agricultural Science.

Global, collaborative wheat research brings enormous gains for developing country farmers, particularly in more marginal environments, according to an article in the Centenary Review of the Journal of Agricultural Science.