Emma Gaalaas Mullaney is a researcher studying gender and agriculture. She has served as a Youth Representative to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and Commission on the Status of Women since 2010.

Emma Gaalaas Mullaney is a researcher studying gender and agriculture. She has served as a Youth Representative to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and Commission on the Status of Women since 2010.

What is your field of research?

I am currently pursuing a dual-PhD in Geography and Women’s Studies at Pennsylvania State University. My dissertation centers on an ethnography of maize production in the eastern Central Highland region of Mexico. I lived in the region for over a year, conducting livelihood studies and oral histories with small-scale, commercially-oriented maize farmers in the Amecameca Valley, and with agricultural extension technicians and scientific researchers working in the nearby Texcoco Valley.

How does gender figure into your research?

My research engages gender in multiple ways. For example, I work closely with farming households and analyze the gendered divisions of labor and decision-making involved in agricultural production. I conducted the oral histories and participatory observation with both female and male members of a given family who are involved in different aspect of maize cultivation, use, and marketing. I also work with both female and male agricultural extension agents and scientists, examining commonalities and differences in their work experiences and practices. I am interested in how gender interacts with other forms of social difference to shape our work and our everyday lives.

What drew you to this work?

I was raised in the rural Midwest (United States), and my extended family has grown corn and soybeans in south-central Wisconsin for generations. The lived experiences of those who work in agriculture has always been a deep interest of mine. I have found that paying close attention to what’s going on with food producers – or with farmers who no longer produce food for human consumption, as is the case for corn growers in the United States – can yield important insight into the strengths and failings of our society. Over the years, as my interests in agriculture and social justice have taken me through many different spaces of formal education, policy negotiation, and scholarly debate, I often gain the most inspiration and understanding while hanging out in fields, in kitchens, and in street markets. Ultimately, my work as a researcher is guided by and accountable to what’s happening on the farm.

When you were gathering the oral histories did certain themes or consistencies emerge?

The oral histories offer rich detail into the livelihoods of different actors and the challenges they face in their daily work routines. As these narratives make abundantly clear, each of the farmers, extension agents, and researchers with whom I spoke is an expert in her or his field. Moreover, they all expressed a high degree of ingenuity and innovation in their work, though this creativity was not necessarily rewarded by their respective institutions. The oral histories also highlighted the gendered divisions of labor among these agricultural workers. Though both women and men worked in leading positions – whether as farmers and maize vendors, as directors of extension teams, or as heads of research departments – the women consistently faced greater risks and uncertainties in their job. In every case I encountered, women took primary responsibility for the household management and decision-making that fell outside of their official job (childcare, bills, etc), putting them in a more highly pressured and less predictable position than their male counterparts. Women were also more likely to find their innovative ideas and contributions dismissed by colleagues on a regular basis, and many described feeling consistently like an outsider in their own work environment.

When you were gathering the oral histories what surprised you?

I did not expect to find such dramatic differences in the level of authority and control that women had over their own work among farming households as compared to women working as extension agents or scientific researchers. Though strict gender roles are perhaps more obvious in the rural farming communities of the Amecameca Valley – where men take charge of the planting, harvesting, and other fieldwork and women handle much of the food preparation, seed selection, and selling of maize in regional street markets – women in these communities are the undisputed experts in the work that they do, which grants them a great deal of space for creative problem solving and risk management on behalf of their family and the local maize economy. In contrast, women working as agricultural technicians, engineers, and researchers are in an environment where gender equality is an explicit priority, but where the standard worker in their position is, and has historically been, male. These women described finding themselves competing for recognition in a setting that often undervalues their individual insights and capabilities.

Do you think there are misconceptions about the research you’ve chosen to pursue?

Well, judging by a common response to my academic affiliation, many people mistakenly assume that, since I come from a Women’s Studies Department, I must begin my research by looking around for women. In fact, I begin my research by asking how particular agricultural systems work, and who is empowered or excluded by these systems. Gender is a force that shapes the agricultural practices and opportunities of both women and men around the world, and it is therefore necessary that I am well trained in gender analysis in order to ask the questions that I do. Gender, interacting with other forms of social difference, dictates who does what kind of work, whether that work is recognized or valued, who has access to resources such as land and credit, and who is allowed to speak with authority on a given subject. Understanding how gender functions is therefore essential to understanding how agriculture is happening and how to improve it. This is true even, perhaps especially, when I walk onto a cornfield, or into an office or lab and encounter only men.

Generally speaking, what are the conclusions your research revealed?

Given that I am still in the process of analyzing data from my dissertation research, I have not yet finished drawing conclusions about maize production in the eastern Central Highlands and its implications for development and biodiversity conservation. At the same time, there are clear themes that have emerged over the course of my fieldwork and which resonate with existing interdisciplinary research. By far the most prominent are the interdependence of innovation and diversity, and their combined importance in agricultural production. Diversity, in terms of maize germplasm, cultivation strategies, and economic systems, is both a resource for and product of innovation in agricultural production, and is a primary source of resilience for small-scale farming households in the Amecameca Valley. A diverse set of perspectives, specialties, and lived experiences is also an obvious source of creativity and innovation among agricultural extension agents and scientific researchers. My research highlights that the strongest and most productive work environments are those that foster these forms of diversification.

What did you discover about gender and agriculture in Mexico?

The most important lessons that I learned about gender and agriculture, after over a year of fieldwork in Mexico’s Central Highlands, are for the most part not new discoveries at all. Decades and decades of extensive research has shown that gender is not merely one social factor among many, one that may or may not be relevant in a given situation. Rather, gender is a dominant social institution that is guaranteed to play a role in shaping agricultural outcomes, even though this process takes many different forms in different places. That Mexico, along with countries around the world, including the United States, currently has such a high degree of gender inequality has devastating consequences for those whose work is ignored or undervalued, and for agricultural production as a whole. Perhaps the new lesson offered by my research is that these very old patterns of inequality still persist today.

What types of changes (policy, research, etc.) do you think would help women and families in Mexico?

There must be public accountability for gender inequality and violence. The different types of gender injustice occurring in Mexico today are not equivalent, but invisible women farmers, gender discrimination in the workplace, and femicide are all products of a society that systematically devalues women’s work and their lives. This is not a problem that is caused by individuals acting alone, nor is it one that can be solved at the individual level; public policy must be held responsible for the fact that gender inequality continues to increase in the face of economic restructuring and global climate change. One important starting point, that is also an important part of any ongoing solution, would be for researchers and policymakers alike to listen carefully to the many women who are already struggling for change.

Finally, I’d like to express my heartfelt thanks to everyone who has worked with me in my research. I am indebted to all the farmers, extension agents, and researchers who graciously allowed me to interview them and to poke my nose into their lives. They do such important, inspiring work, and I look forward to building on these relationships in future research.

Pusa Krishi Vigyan Mela, a farmers’ fair organized by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) annually since 1972, was held during 6-8 March 2013 in New Delhi, India. Every year, agriculture institutes and universities gather at the fair to disseminate their upgraded technology through exhibitions. This year, the focus was on “Agricultural technologies for farmers’ prosperity” and for the very first time IARI invited CGIAR centers, including CIMMYT, to display their technological innovation and experience.

Pusa Krishi Vigyan Mela, a farmers’ fair organized by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) annually since 1972, was held during 6-8 March 2013 in New Delhi, India. Every year, agriculture institutes and universities gather at the fair to disseminate their upgraded technology through exhibitions. This year, the focus was on “Agricultural technologies for farmers’ prosperity” and for the very first time IARI invited CGIAR centers, including CIMMYT, to display their technological innovation and experience. The socioeconomics team of CIMMYT India (Mamta Mehar and Subash Ghimire) also joined the fair to interact with farmers and learn about their perspectives on new technologies and farming-related constraints. Although the farmers came from different states, they mentioned having several common problems: the unavailability of quality seeds and other input on time, weather uncertainty, unpredictability of rainfall, and temperature variability. Farmers from Haryana and Rajasthan also talked about increasing pollution, degrading soil quality, and emergence of new type of insects and pests for which they would like to seek solutions. They were concerned about limited access to knowledge and low awareness on new technologies, especially those that help to manage climate change related risks. The socioeconomics team also learned that farmers are aware that using more than the advised amount of fertilizers and pesticides may harm the soil, but they do so anyways because they are afraid of the appearance of insects, pests, etc. as a result of unforeseen weather changes.

The socioeconomics team of CIMMYT India (Mamta Mehar and Subash Ghimire) also joined the fair to interact with farmers and learn about their perspectives on new technologies and farming-related constraints. Although the farmers came from different states, they mentioned having several common problems: the unavailability of quality seeds and other input on time, weather uncertainty, unpredictability of rainfall, and temperature variability. Farmers from Haryana and Rajasthan also talked about increasing pollution, degrading soil quality, and emergence of new type of insects and pests for which they would like to seek solutions. They were concerned about limited access to knowledge and low awareness on new technologies, especially those that help to manage climate change related risks. The socioeconomics team also learned that farmers are aware that using more than the advised amount of fertilizers and pesticides may harm the soil, but they do so anyways because they are afraid of the appearance of insects, pests, etc. as a result of unforeseen weather changes.

The 2nd Latin American Convention on Airtight Storage sponsored by the global company GrainPro, Inc was held during 1-2 March 2013 in Antigua, Guatemala. More than 50 participants from Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and the USA, and other countries attended the event.

The 2nd Latin American Convention on Airtight Storage sponsored by the global company GrainPro, Inc was held during 1-2 March 2013 in Antigua, Guatemala. More than 50 participants from Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and the USA, and other countries attended the event. For over 10 years, CIMMYT has been working assiduously with the national agriculture research system of Afghanistan to contribute to the war-torn country’s sustainable agricultural growth and research and development. So far, the joint efforts have led to the release of 12 wheat, 4 maize, and 2 barley varieties. As wheat and maize together account for about 84% of cereal acreage and production in Afghanistan, the work continues. During 5-7 March 2013, CIMMYT director general Thomas Lumpkin visited Afghanistan to observe CIMMYT activities and initiate a dialogue on further cooperation.

For over 10 years, CIMMYT has been working assiduously with the national agriculture research system of Afghanistan to contribute to the war-torn country’s sustainable agricultural growth and research and development. So far, the joint efforts have led to the release of 12 wheat, 4 maize, and 2 barley varieties. As wheat and maize together account for about 84% of cereal acreage and production in Afghanistan, the work continues. During 5-7 March 2013, CIMMYT director general Thomas Lumpkin visited Afghanistan to observe CIMMYT activities and initiate a dialogue on further cooperation.

Many scientists begin exploring at a young age; they try to figure out the things they don’t know, ask questions of others, and see how this information might be useful to them in creating new knowledge. The very lucky ones might have a mentor, or at the very least, a place where they are encouraged to cultivate their curiosity and use what they find out to help others.

Many scientists begin exploring at a young age; they try to figure out the things they don’t know, ask questions of others, and see how this information might be useful to them in creating new knowledge. The very lucky ones might have a mentor, or at the very least, a place where they are encouraged to cultivate their curiosity and use what they find out to help others. In the continuous effort to increase awareness of wheat biofortification and its use to improve health and quality of life in eastern India, Banaras Hindu University (

In the continuous effort to increase awareness of wheat biofortification and its use to improve health and quality of life in eastern India, Banaras Hindu University ( Over 100 stakeholders, scientists, and students from 28 countries were welcomed in Obregon, Mexico, by John Snape, CIMMYT Board of Trustees member, as he opened the 3rd International Workshop of the Wheat Yield Consortium (WYC). The meeting sponsored by SAGARPA (through

Over 100 stakeholders, scientists, and students from 28 countries were welcomed in Obregon, Mexico, by John Snape, CIMMYT Board of Trustees member, as he opened the 3rd International Workshop of the Wheat Yield Consortium (WYC). The meeting sponsored by SAGARPA (through  The first day was dedicated to over 20 presentations covering all three major research areas. Chaired by Bill Davies (

The first day was dedicated to over 20 presentations covering all three major research areas. Chaired by Bill Davies (

Thomas Lumpkin, CIMMYT director general, and Marianne Bänziger, deputy director general for research and partnerships, visited CIMMYT-Bangladesh during 20-23 February 2013 to meet with CIMMYT-Bangladesh personnel, government officials, and representatives from key national agricultural research systems. They toured the fields of the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia in Bangladesh (

Thomas Lumpkin, CIMMYT director general, and Marianne Bänziger, deputy director general for research and partnerships, visited CIMMYT-Bangladesh during 20-23 February 2013 to meet with CIMMYT-Bangladesh personnel, government officials, and representatives from key national agricultural research systems. They toured the fields of the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia in Bangladesh (

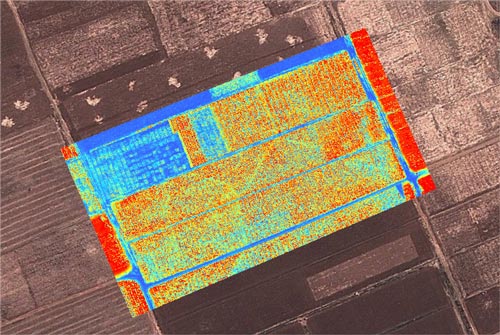

To free phenotyping of the varietal development bottleneck label, many new tools have been developed to enable an easier plant growth and development characterization and field variability. Until recently, these tools’ potential has been limited by the scale on which they can be used, but this is changing: a new affordable field-based phenotyping platform combining cutting edge aeronautics technology and image analysis was developed through collaboration between researchers from the

To free phenotyping of the varietal development bottleneck label, many new tools have been developed to enable an easier plant growth and development characterization and field variability. Until recently, these tools’ potential has been limited by the scale on which they can be used, but this is changing: a new affordable field-based phenotyping platform combining cutting edge aeronautics technology and image analysis was developed through collaboration between researchers from the  The new platform uses ‘Sky Walker,’ an unmanned aerial vehicle which can fly at over 600-meter with an average speed of 45 km/h. The vehicle has thermal and spectral cameras mounted under each wing, and its flight path and image capturing are controlled via a laptop using Google Earth images. Jill Cairns and Mainassara Zaman-Allah tested the platform at CIMMYT-Harare along with José Luis Araus (University of Barcelona), Antón Fernández (AirElectronics president), and Alberto Hornero (Sustainable Agricultural Institute of the High Research Council) to establish the optimal flight path (distance between plane passes and height) for plot level measurements. Field experiments were phenotyped for spectral reflectance and canopy temperature within minutes; these will be compared to results from the GreenSeeker.

The new platform uses ‘Sky Walker,’ an unmanned aerial vehicle which can fly at over 600-meter with an average speed of 45 km/h. The vehicle has thermal and spectral cameras mounted under each wing, and its flight path and image capturing are controlled via a laptop using Google Earth images. Jill Cairns and Mainassara Zaman-Allah tested the platform at CIMMYT-Harare along with José Luis Araus (University of Barcelona), Antón Fernández (AirElectronics president), and Alberto Hornero (Sustainable Agricultural Institute of the High Research Council) to establish the optimal flight path (distance between plane passes and height) for plot level measurements. Field experiments were phenotyped for spectral reflectance and canopy temperature within minutes; these will be compared to results from the GreenSeeker.

Marianne started her career with CIMMYT as a post-doctoral fellow in 1994 working in Maize Physiology to develop varieties tolerant to low soil fertility and drought. She was based at the CIMMYT office in Zimbabwe during 1996-2004, after which she was appointed Director of the Maize Program, based in Nairobi. In 2009 Marianne became the DDG-Research. In that capacity, she led the development of the CGIAR research programs for maize and wheat.

Marianne started her career with CIMMYT as a post-doctoral fellow in 1994 working in Maize Physiology to develop varieties tolerant to low soil fertility and drought. She was based at the CIMMYT office in Zimbabwe during 1996-2004, after which she was appointed Director of the Maize Program, based in Nairobi. In 2009 Marianne became the DDG-Research. In that capacity, she led the development of the CGIAR research programs for maize and wheat. Emma Gaalaas Mullaney is a researcher studying gender and agriculture. She has served as a Youth Representative to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and Commission on the Status of Women since 2010.

Emma Gaalaas Mullaney is a researcher studying gender and agriculture. She has served as a Youth Representative to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and Commission on the Status of Women since 2010.