Nepalese wheat researchers trained on spot blotch disease in India

Spot blotch is one of the major diseases in the wheat growing regions of Nepal and the knowledge allowing researchers to identify and understand the disease is thus crucial. A group of 12 wheat technical research staff from Nepal visited Banaras Hindu University (BHU) in Varanasi, India, during 18-21 March 2013 with that purpose exactly: to learn more about the spot blotch disease and participatory varietal selection. The training was coordinated by CIMMYT wheat breeder Arun Joshi under the CRP WHEAT Strategic Initiative 5: durable resistance and management of diseases and insect pests. The main resource persons for the training were Ramesh Chand, Vinod Kumar Mishra, and B. Arun; Naji Eisa (Yemen), Conformt Sankem (Nigeria), Chhavi Tiwari, and Punam Yadav (India), all PhD students from BHU, facilitated the program.

Spot blotch is one of the major diseases in the wheat growing regions of Nepal and the knowledge allowing researchers to identify and understand the disease is thus crucial. A group of 12 wheat technical research staff from Nepal visited Banaras Hindu University (BHU) in Varanasi, India, during 18-21 March 2013 with that purpose exactly: to learn more about the spot blotch disease and participatory varietal selection. The training was coordinated by CIMMYT wheat breeder Arun Joshi under the CRP WHEAT Strategic Initiative 5: durable resistance and management of diseases and insect pests. The main resource persons for the training were Ramesh Chand, Vinod Kumar Mishra, and B. Arun; Naji Eisa (Yemen), Conformt Sankem (Nigeria), Chhavi Tiwari, and Punam Yadav (India), all PhD students from BHU, facilitated the program.

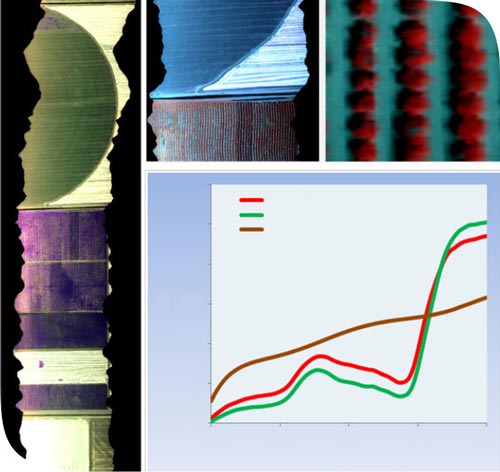

The training covered identification of spot blotch pathogen Bipolaris sorokiniana in the field and the lab; preparation of Bipolaris inoculum using colonized sorghum grain; understanding the spot blotch disease infection process; creating artificial epiphytotic in the polyhouse and the field; screening wheat genotypes under high humidity and temperature in the polyhouse; recording disease severity in field and polyhouse conditions; and increasing data reliability in research on spot blotch of wheat and barley.

Participants first visited the pathology laboratory in the Mycology and Plant Pathology department, where they learned to identify B. sorokiniana under the microscope and to prepare Bipolaris inoculums from colonized sorghum grain. The infection process was explained using different samples available in the lab, as was a new technique for evaluation of spot blotch resistance in barley and wheat using monoconidial culture of the most aggressive isolate of B. sorokiniana developed at BHU. Participants observed the collection of the blotched portions of infected leaves for the production of conidia by associated fungal hyphae. They were also trained in conidia collection for further multiplication and categorization into different classes based on the aggressiveness of isolates.

On the second day, participants visited the polyhouse and research station to learn about screening wheat genotypes

On the second day, participants visited the polyhouse and research station to learn about screening wheat genotypes

under high humidity and temperature. They recorded the disease severity a number of times and saw that if inoculation is done properly the susceptible genotypes burn. The variation among genotypes for resistance to spot blotch disease was explained with the help of repeated disease notes and developing area under disease progress curve. Participants also observed the CRP project on spot blotch carried out at BHU in collaboration with the Nepal Wheat Research Program. The visiting team fruitfully interacted with the BHU wheat researchers, especially with Chand and Mishra, as well as with master’s and doctoral students working on spot blotch. A planned one-hour question-and-answer session expanded to three hours due to the visitors’ enthusiasm and wide-ranging questions.

On their final day, the team visited three participatory varietal selection sites where Harikirtan Singh, the lead farmer, demonstrated the performance of the most popular and newly developed lines under different seeding conditions (surface seeding, zero tillage, and conventional tillage) and multiplication of a number of agronomically superior zinc-rich wheat lines selected from the HarvestPlus project.

The training also allowed participants to visit other research experiments and trials associated with the Cereal System Initiative South Asia (CSISA) and HarvestPlus projects, and to learn to identify agronomically superior biotic and abiotic resistant varieties.

The Nepalese team regarded the visit highly successful as it provided an excellent opportunity to work with the most recent tools and techniques in spot blotch and other wheat researches and to enrich their experience on proper data recording and conduct of participatory varietal selection trials.

On 02 May 2013, the Water Efficient Maize for Africa (

On 02 May 2013, the Water Efficient Maize for Africa (

From 29 April to 10 May, 16 agricultural engineers, agronomists, machinery importers, and machinery manufacturers from Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe took part in a study tour in India organized by CIMMYT, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (

From 29 April to 10 May, 16 agricultural engineers, agronomists, machinery importers, and machinery manufacturers from Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe took part in a study tour in India organized by CIMMYT, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (

Breeding of durable resistance to stripe rust —the greatest biotic threat to wheat production in the largest wheat producer and consumer in the world, China— was the major theme of a workshop jointly organized by the CIMMYT-Sichuan office and the Sichuan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (SAAS) at the SAAS Plant Breeding Institute in Chengdu, Sichuan province, China, on 18 May 2013. The workshop aimed to promote the adoption of second-generation parents and slow-rusting breeding strategies in spring wheat-producing areas of China and to facilitate collaborative breeding strategies between SAAS and its sister organizations in neighboring provinces. The workshop consisted of a seminar and a discussion session on germplasm and breeding strategies led by Gary Rosewarne (CIMMYT Global Wheat Program senior scientist) and Bob McIntosh (Emeritus Professor at the

Breeding of durable resistance to stripe rust —the greatest biotic threat to wheat production in the largest wheat producer and consumer in the world, China— was the major theme of a workshop jointly organized by the CIMMYT-Sichuan office and the Sichuan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (SAAS) at the SAAS Plant Breeding Institute in Chengdu, Sichuan province, China, on 18 May 2013. The workshop aimed to promote the adoption of second-generation parents and slow-rusting breeding strategies in spring wheat-producing areas of China and to facilitate collaborative breeding strategies between SAAS and its sister organizations in neighboring provinces. The workshop consisted of a seminar and a discussion session on germplasm and breeding strategies led by Gary Rosewarne (CIMMYT Global Wheat Program senior scientist) and Bob McIntosh (Emeritus Professor at the

The Nutritious Maize for Ethiopia (NuME) aims to develop and promote quality protein maize (QPM) in the major maize growing areas of Ethiopia, including the highlands and the dry lands, to improve nutritional status of children. The project has a strong gender component, ensuring women’s full participation in all activities and equal share of benefits, which was discussed during a Gender Analysis and Strategy workshop at the

The Nutritious Maize for Ethiopia (NuME) aims to develop and promote quality protein maize (QPM) in the major maize growing areas of Ethiopia, including the highlands and the dry lands, to improve nutritional status of children. The project has a strong gender component, ensuring women’s full participation in all activities and equal share of benefits, which was discussed during a Gender Analysis and Strategy workshop at the  On 26-27 April 2013, the

On 26-27 April 2013, the  The project has generally been considered very successful. “We now know which mycotoxins are important in the region and we have the products to potentially minimize the risk,” commented Mahuku. “What we need is to widely test and disseminate the products so that they reach as many farmers as possible. With a little infusion of resources, the dedication demonstrated by this group, and support from policy makers, I have no doubt that we will get there.”

The project has generally been considered very successful. “We now know which mycotoxins are important in the region and we have the products to potentially minimize the risk,” commented Mahuku. “What we need is to widely test and disseminate the products so that they reach as many farmers as possible. With a little infusion of resources, the dedication demonstrated by this group, and support from policy makers, I have no doubt that we will get there.” “I am so excited to be here,” said Dr. Evangelina Villegas as she received her Outstanding Alumni Award from the Department of Grain Science and Industry at the Kansas State University (

“I am so excited to be here,” said Dr. Evangelina Villegas as she received her Outstanding Alumni Award from the Department of Grain Science and Industry at the Kansas State University ( The Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS)

The Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) Conservation agriculture methods enable producers to sustainably intensify production, improve soil health, and minimize or avoid negative externalities. However, these practices have not yet taken off in most Central Asian countries. The

Conservation agriculture methods enable producers to sustainably intensify production, improve soil health, and minimize or avoid negative externalities. However, these practices have not yet taken off in most Central Asian countries. The