Seed systems in a snapshot

“Reducing post-harvest losses is key to increasing availability of food as it is not only important to increase domestic food production but also to protect what is produced by minimizing losses,” stated Zechariah Luhanga, Permanent Secretary, Provincial Administration at the Office of the President, Eastern Province, at the Provincial Stakeholders Workshop on Effective Grain Storage for Sustainable Livelihoods of African Farmers Project (EGSP-II) held in Chipata, Zambia, on 29 May 2013. “We as the key stakeholders and participants in the agricultural sector can enhance food security and improve incomes of resource poor farmers and artisans by promoting improved storage technologies such as metal silos and hermetic bags in Zambia.”

“Reducing post-harvest losses is key to increasing availability of food as it is not only important to increase domestic food production but also to protect what is produced by minimizing losses,” stated Zechariah Luhanga, Permanent Secretary, Provincial Administration at the Office of the President, Eastern Province, at the Provincial Stakeholders Workshop on Effective Grain Storage for Sustainable Livelihoods of African Farmers Project (EGSP-II) held in Chipata, Zambia, on 29 May 2013. “We as the key stakeholders and participants in the agricultural sector can enhance food security and improve incomes of resource poor farmers and artisans by promoting improved storage technologies such as metal silos and hermetic bags in Zambia.”

The workshop had five main objectives: (1) to provide a forum for exchange of ideas, information, and research outputs on EGSP-II among stakeholders in Chipata; (2) to raise awareness on post-harvest losses and dissemination of effective grain storage technologies among provincial stakeholders; (3) to consult provincial stakeholders on effective postharvest technologies, policy environment, and market issues for the purpose of refining, updating, and implementing EGSP-II; (4) to engage in policy dialogue on matters related to storage and find means of enhancing adoption of the technology; and (5) to acquaint key stakeholders in the province with the post-harvest technology and ways to enhance its adoption among farmers.

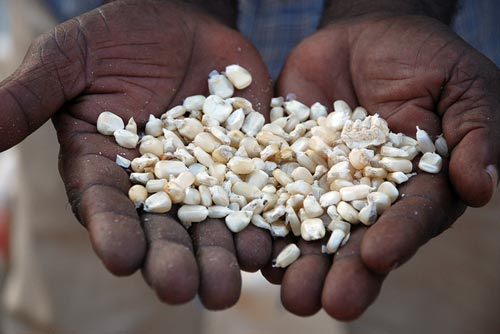

Maize suffers heavy post-harvest losses estimated at 20-30%. “The main underlying factor is that most of the small-scale farmers do not have access to improved storage facilities,” explains Tadele Tefera, CIMMYT entomologist and EGSP-II coordinator. Ivor Mukuka, EGSP national coordinator for Zambia, noted that since the larger grain borer was first found in Zambia in 1993, there have been sporadic outbreaks causing substantial losses in maize. “For instance, rapid loss assessments in Lundazi and Chama districts revealed losses ranging from 5-74%. Other studies indicate storage losses of between 45-90% based on farmers’ estimation,” he added.

Luhanga reminded participants that grain post-harvest management development requires active participation of all stakeholders, including government, research systems, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector in bringing the technologies to farmers’ doorsteps. “You need to make sure to set priority activities so that they address the challenges faced by smallholder farmers regarding maize grain post-harvest management, but also expand their opportunities in the maize sector,” Luhanga urged more than 50 stakeholders present in the meeting.

Besides post-harvest loss reduction, the metal silo technology provides huge business opportunities to artisans. “Engaging in metal silo fabrication and marketing can create jobs and rural enterprise development,” said Egbet Munganama, principal agricultural engineer at the Department of Mechanization, Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Zambia. According to Jones Govereh, EGSP policy analyst, artisans can earn over US$ 3,000 per year if they fabricates just five silos a month on average. “This is an attractive income for micro-entrepreneurs but commercially oriented entrepreneurs can earn much more,” he explained.

“Improved maize storage technologies have a great potential impact on food security as most households lose much of their maize due to poor storage facilities,” concluded CIMMYT principal economist Hugo De Groote, considering that maize is the major food crop in Zambia.

Tadele thanked the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) for funding EGSP-II, a project aiming to reduce post-harvest losses, enhance food security, and improve incomes of resource-poor farmers in Zambia.

Rajasthan is one of the most stress-prone dry states of India, where farmers grow maize as major crop for food and domestic consumption. As such, it provided a perfect setting for the 2nd Annual Progress Review and Planning Meeting for the Abiotic Stress Tolerant Maize for Asia (ATMA) project. The meeting, jointly organized by the Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology (MPUAT) and CIMMYT, took place at MPUAT in Udaipur, Rajasthan, during 5-6 June 2013.

Rajasthan is one of the most stress-prone dry states of India, where farmers grow maize as major crop for food and domestic consumption. As such, it provided a perfect setting for the 2nd Annual Progress Review and Planning Meeting for the Abiotic Stress Tolerant Maize for Asia (ATMA) project. The meeting, jointly organized by the Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology (MPUAT) and CIMMYT, took place at MPUAT in Udaipur, Rajasthan, during 5-6 June 2013.

ATMA is an Asian regional collaborative initiative led by CIMMYT aimed at increasing income and food security of the resource-poor in South and Southeast Asia. The project connects national agricultural research systems, including the Directorate of Maize Research (DMR), India; MPUAT, India; Acharya NG Ranga Agricultural University, India; National Maize Research Institute (NMRI), Vietnam; Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI); Institute of Plant Breeding at the University of the Philippines, Los Baños (IPB-UPLB), Philippines; and the University of Hohenheim, Germany. The project is supported by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

During his welcome speech addressing participants representing all ATMA collaborators, R.B. Dubey (MPUAT) highlighted the importance of partnerships between CIMMYT and regional institutions, especially for addressing such complex issues as tolerance to abiotic stresses in maize. The welcome address launched the opening session chaired by vice-chancellor of MPUAT-Udaipur Om Prakash Gill. This session consisted of presentations by MPUAT research director P.L. Paliwal, who focused on the university’s contributions to agricultural development in general and maize improvement for food security and income of Rajasthan farmers in particular, and by B.S. Vivek (CIMMYT) who talked about the importance of abiotic stresses in maize production in Asia.

The session’s chairman added: “Our maize farmers have many choices regarding high-yielding varieties and technologies for optimal conditions, and they are experts in achieving high yields under such conditions. But when it comes to stress conditions they have very few choices, and that is where they need our intervention.”

The session’s chairman added: “Our maize farmers have many choices regarding high-yielding varieties and technologies for optimal conditions, and they are experts in achieving high yields under such conditions. But when it comes to stress conditions they have very few choices, and that is where they need our intervention.”

During a session on annual progress review, the ATMA project leader P.H. Zaidi gave a brief overview of the project, indicating the commitments and milestones. Avinash Singode (DMR), Dang Ngoc Ha (NMRI), Reshma Sultana (BARI), and Ayn Christina (IPB-UPLB) then presented on the project’s progress over the past year, and CIMMYT’s Zaidi and Raman Babu covered the work done by CIMMYT and partners, as well as the status of progress on various outputs of the project. Christian Boeber (CIMMYT) and V.K. Yadav (DMR) jointly summarized the socioeconomic component and provided field survey results, and CIMMYT’s Kai Sonder and Pardhasaradhi Teluguntla discussed spatial analysis with focus on the progress in mapping maize production zones and stress-prone target ecologies in South Asia.

The afternoon session, led by CIMMYT-Hyderabad post-doctoral fellow M.T. Vinayan, focused on work plan creation, assigning tasks to partners, and activities for next year. Opportunities for further research and learning provided by ATMA were also discussed, reflecting upon previous events, including a capacity building workshop on doubled haploid in maize breeding attended by ATMA partners at the University of Hohenheim, Germany, during 12-15 April 2012, and training on precision phenotyping for abiotic stress tolerance in maize during 29 August – 1 September 2012 at CIMMYT-Hyderabad. Furthermore, two interns – one from Bangladesh and one from Vietnam – were trained on the key aspects of breeding for enhancing water-logging and drought tolerance in maize at CIMMYT-Hyderabad from 1 August to 16 September 2012.

On the second day of the meeting, the team visited a nearby village to interact with maize farmers living in a stressprone agro-ecology. Dilip Singh, MPUAT, introduced the participants to farmers of the Fathnagar village where Bhanwar Lal Paliwal, an 84-year-old farmer who still spends four to six hours per day in the field, shared his experience with agriculture and maize. “I have been growing maize since I was a child,” he said, “maize is major part of my daily diet which is why I am still strong and fit even at the age of 84.” Paliwal then shared a famous local saying – Makki ki roti khayege, Rajasthan chhor ke kahi nahi jayege, meaning “we will eat corn bread and never leave Rajasthan” – and added that although there have been many new maize varieties introduced in the region in recent years, they are less stress tolerant in comparison to the old local varieties. “New high-yielding hybrids with tolerance to drought stress are much needed, as rainfall is declining, or becoming more erratic, every year,” he urged the ATMA team to continue their much appreciated work. “I am looking forward to stress resilient maize varieties that will help us harvest good yields even in bad years,” added Paliwal.

The farmer-scientist interaction produced very useful insights into the issues faced by maize farmers in the region and reiterated the importance of stress tolerant maize varieties for their livelihood. To conclude the day, farmers prepared and shared various maize dishes with the delegation.

The farmer-scientist interaction produced very useful insights into the issues faced by maize farmers in the region and reiterated the importance of stress tolerant maize varieties for their livelihood. To conclude the day, farmers prepared and shared various maize dishes with the delegation.

The International Conservation Agriculture Forum, held at the Ningxia Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences in Yinchuan during 27-31 May, was attended by a significant number of provincial government officials and private sector representatives who joined to discuss national and international partnerships in farming system intensification, mechanization, nutrient-use efficiency, precision agriculture, and training; gain better understanding of what conservation agriculture is; jointly identify needs, priorities, and constraints to broad adoption of conservation agriculture in China; and explore the Cropping Systems Intensification Project for North Asia (CSINA).

Key academic leaders from across China briefed the international participants, including Bruno Gerard, Ivan Ortiz-Monasterio, M.L. Jat, Scott Justice, Dan Jeffers, and Garry Rosewarne from CIMMYT, Wang Guanglin from ACIAR, and Rabi Raisaily, international liaison for Haofeng Machinery. Some key constraints to adoption of conservation agriculture were covered, including the lack of financial, political, and personal incentives; inadequate or unavailable zero-till machinery; inflexible irrigation-water distribution and fixed pricing; narrow approach to research, development, and engineering without linkages to the larger issues of farming and cropping systems; and limited knowledge of rural socioeconomic conditions. Consequently, the participants defined future priorities: a socioeconomic study covering labor, gender, impacts of previous projects, and adoption issues; and mechanization development and plant residue trade-offs and handling, especially of rice/wheat systems.

One of the most important outcomes of the forum was the establishment of new relationships with the China Agricultural University, Nanjing Agricultural University, Sichuan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the Northwest Agricultural and Forestry University, and others. Similarly, invigorating of old partnerships with the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences is expected to be highly beneficial for future research platform development.

As partnerships with machinery manufacturers are often crucial in driving the uptake of conservation agriculture by creating a push demand for conservation agriculture machinery, the presence of private sector representatives, including the Henan Haofeng Machinery Manufacturing Company (Henan province), Qingdao Peanut Machinery Company (Shandong province), Jingxin Agricultural Machinery (Sichuan province), and the International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI), was crucial. The importance of such partnerships has been proven before; for example, the research and development activities of the Qingdao Peanut Machinery Company have seen a considerable advancement of the Chinese Turbo Happy Seeder, which has been downsized through a number of iterations to suit tractors with less than 30 hp. Thanks to this public-private interaction, the forum participants learned about preliminary discussions to prototype the two-wheel tractor Happy Seeder specifically for Africa and joint CIMMYT/ACIAR projects. “We are hopeful that one of the companies present at the forum will take up this opportunity to create demand for conservation agriculture machinery for the small landholder,” said CIMMYT senior cropping systems scientist Allen McHugh.

The forum, jointly organized by the Ningxia Provincial Government Foreign Experts Bureau, Ningxia Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, and CIMMYT, was regarded very successful, as it has advanced CIMMYT’s stakes in future funding requests. “Overall, we have had a very good start toward the development of integrated research platforms in three distinct agro-ecological zones. The next step is to consolidate the outcomes from the forum and commence the iterative process of project development,” McHugh added, summarizing the results of the event.

The past few weeks have been busy and interesting in China: preparing for the International Conservation Agriculture Forum in Yinchuan and work travels to Beijing, Yangling (Shaanxi province), and Xuchang (Henan province) are a sure way to keep oneself occupied.

The past few weeks have been busy and interesting in China: preparing for the International Conservation Agriculture Forum in Yinchuan and work travels to Beijing, Yangling (Shaanxi province), and Xuchang (Henan province) are a sure way to keep oneself occupied.

Strengthening partnerships in Beijing

I travelled to Beijing during 2-4 May to discuss future cooperation between the University of Southern Queensland (USQ) and the China Agricultural University (CAU) at a meeting with Jan Thomas, USQ vice-chancellor, and K.E. Bingsheng, CAU president, accompanied by the USQ delegation and CAU senior professors. What does this have to do with CIMMYT? Part of my mandate in China is to forge new partnerships, especially with universities seeking to expand internationally. This requires putting on the CIMMYT uniform to demonstrate presence and reinforce linkages with old and new colleagues. As a result, we hope to see a memorandum of understanding and the facilitation of staff and student exchanges between these universities, Ningxia institutions, and CIMMYT.

Water-use efficiency in Yangling

The Northwest Agricultural and Forestry University in Yangling hosted the final review of the ACIAR “More effective water use by rainfed wheat in China and Australia” project led by Tony Condon (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, CSIRO), in which the Ningxia Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences is a partner (led by Yuan Hanmin). The project aims to improve and stabilize farmer returns from growing wheat in dry, rainfed environments in northwest China through development of higher-yielding wheat germplasm that uses water and soil resources more effectively. I spent 6-10 May first hearing about and seeing the extensive breeding work with Australian and Chinese lines, and later discussing the role of conservation agriculture and soil management in breeding with the reviewers and other participants, including Greg Rebetzke from CSIRO. During a Combined China-EU-Australia Workshop on Phenotyping for Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Water-Use Efficiency in Crop Breeding, which followed the review, Richard Richards (CSIRO) presented a very pertinent paper on “Opportunities to improve cereal root systems for greater productivity.” His focus on below-ground processes provides considerable and significant support for conservation agriculture and associated management practices in improving root system functions.

Farm mechanization in Xuchang

The 30th anniversary of the Henan Haofeng Machinery Manufacturing Company in Xuchang, Henan province, provided an excellent opportunity to present conservation agriculture and small machinery requirements for developing countries to 4 academicians, about 10 high level officials from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Agriculture, Henan Provincial Government, and many highly regarded Chinese mechanization scientists and extension workers.

During 16-18 May, the factory hosted two forums, one focused on combination of wheat agricultural machinery and agronomy, and another on scientific innovation and development of Chinese agricultural machinery. Although the language of the forums was Chinese, my presentation in English was understood by the senior people, some of whom later inquired about the new Chinese Turbo Happy Seeder developed by CIMMYT. The discussion on conservation agriculture per se was limited, but I was able to meet many old Chinese friends and strengthen new relationships for CIMMYT and the Global Conservation Agriculture Program.

After a year of exchanges, planning, and construction, CIMMYT and CMF, a French company manufacturing greenhouses, inaugurated CIMMYT’s new state-of-the-art greenhouses at El Batán on 13 June 2013. The facility is funded by CIMMYT and the Carlos Slim Foundation and is part of a vast laboratory complex opened on 13 February 2013 in the presence of Bill Gates and Carlos Slim.

After a year of exchanges, planning, and construction, CIMMYT and CMF, a French company manufacturing greenhouses, inaugurated CIMMYT’s new state-of-the-art greenhouses at El Batán on 13 June 2013. The facility is funded by CIMMYT and the Carlos Slim Foundation and is part of a vast laboratory complex opened on 13 February 2013 in the presence of Bill Gates and Carlos Slim.

It was a good opportunity for the French Ambassador, Elisabeth Beton Delègue, to come and visit CIMMYT, while supporting a dynamic French enterprise working in Mexico and other parts of the world. She was guided through the visit by Kevin Pixley, Marianne Bänziger, Renaud Josse (director of CMF) and his staff, and Guillermo Simon, representing CARSO, Carlos Slim’s conglomerate company.

“This is a great adventure,” said Beton Delègue. “It is the first time I see a realization of this type, with multiple possibilities allowing a dialogue between researchers and manufacturers and I am proud of our French technology.” CMF has designed a greenhouse of 1,577 m2 consisting of 21 cells that can reproduce different climates. It has its own weather station too. “We work closely with the researchers to define what the real research needs are,” explains Josse. “We try to build the most adequate project. One cell can reproduce a desertic climate, another a tropical climate. We work on the characterization of necessities in terms of temperature gaps and humidity fluctuations among other things.” This precise control of climatic parameters will be of great assistance for CIMMYT’s research on climate change.

The other building to be realized by CMF is a smaller greenhouse of 400 m2 which consists of five sealed cells for biosafety (BSL2 or biosafety level 2). No exchange between indoor and outdoor area will be possible. The project is well underway and should be completed soon.

Marianne Bänziger reflected on the importance of the biosafety guarantee, and appreciated that calling in the experts in the area would certainly lead to higher quality research.

“I am very happy to participate in the inauguration of the greenhouses and to visit CIMMYT,” said Beton Delègue, “and I hope to collaborate with CIMMYT in the future because we have many projects going on which deserve that we meet again.”

For Ravi Singh, CIMMYT distinguished scientist, “the new greenhouses are like a new car model. The good control will help to improve efficiency and obtain better results.”

After months of discussions and debates on the scientific evidence regarding conservation agriculture for small-scale, resource-poor farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, a group of 40 scientists reached a consensus on the goals of conservation agriculture and the research necessary to reach these goals. The discussions leading to the signing of the Nebraska Declaration on Conservation Agriculture on 5 June 2013 began during a scientific workshop on “Conservation agriculture: What role in meeting CGIAR system-level outcomes?” organized by the CGIAR Independent Science and Partnership Council (ISPC) at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA, during 15-18 October 2012. Several CIMMYT scientists contributed to the Lincoln workshop and the subsequent draft of the convention. “Not every participant agreed to sign. It went too far for some conservation agriculture purists and not far enough for others. This is usually the case when a consensus between 50 scientists and experts is sought,” said Bruno Gerard, director of CIMMYT’s Global Conservation Agriculture Program (GCAP), pointing to an interesting read in that respect, ‘Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in Africa: The heretics’ view’ by Giller et al. (2009).

After months of discussions and debates on the scientific evidence regarding conservation agriculture for small-scale, resource-poor farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, a group of 40 scientists reached a consensus on the goals of conservation agriculture and the research necessary to reach these goals. The discussions leading to the signing of the Nebraska Declaration on Conservation Agriculture on 5 June 2013 began during a scientific workshop on “Conservation agriculture: What role in meeting CGIAR system-level outcomes?” organized by the CGIAR Independent Science and Partnership Council (ISPC) at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA, during 15-18 October 2012. Several CIMMYT scientists contributed to the Lincoln workshop and the subsequent draft of the convention. “Not every participant agreed to sign. It went too far for some conservation agriculture purists and not far enough for others. This is usually the case when a consensus between 50 scientists and experts is sought,” said Bruno Gerard, director of CIMMYT’s Global Conservation Agriculture Program (GCAP), pointing to an interesting read in that respect, ‘Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in Africa: The heretics’ view’ by Giller et al. (2009).

According to the Declaration, most efforts to date in developing countries have promoted conservation agriculture as a package of three practices: minimum disturbance of soil, retention of sufficient crop residue, and diversified cropping patterns. However, the situation on the ground shows limits of this strict definition, as there is little evidence of conservation agriculture wide adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, but there is some evidence of adoption of one or two of the components. To play a significant role in low-productivity, resource-poor agricultural systems, broader efforts going beyond a focus on the package of the three main practices are necessary. Emphasis needs to be placed on diagnostic agronomy and participatory on-farm research to identify the constraints faced by farmers and to guide farmers in finding solutions to them. As there is a range of sound agronomic, economic, and/or social reasons for choosing not to adopt the three-component conservation agriculture package, it is necessary to systematically assess the suitability and viability of management options and practices while considering farmers’ objectives and constraints, the Declaration stresses.

Rigorous and coordinated research is needed to assess and better understand the process of adoption of conservation agriculture. Unless the farmers’ reasons for choosing to adopt or not to adopt a certain practice are known, a wider adoption of conservation agriculture practices is unlikely.

“I think the declaration is useful as conservation agriculture principles should be seen as a way to sustainable intensification and not an end by itself,” commented Gerard. “The declaration fits well with the present efforts of GCAP and the Socioeconomics Program to put conservation agriculture in a broader context, and to better understand adoptability and constraints to adoption, which are agroecology-, site-, and farm-specific. Furthermore, it stretches the importance of systems research to integrate field level agronomy work within a multi-scale and multi-disciplinary framework.”

The maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease first appeared in Kenya’s Rift Valley in 2011 and quickly spread to other parts of Kenya, as well as to Uganda and Tanzania. Caused by a synergistic interplay of maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV) and any of the cereal viruses in the family, Potyviridae, such as Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV), Maize dwarf mosaic virus (MDMV), or Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV), MLN can cause total crop loss if not controlled effectively.

The maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease first appeared in Kenya’s Rift Valley in 2011 and quickly spread to other parts of Kenya, as well as to Uganda and Tanzania. Caused by a synergistic interplay of maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV) and any of the cereal viruses in the family, Potyviridae, such as Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV), Maize dwarf mosaic virus (MDMV), or Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV), MLN can cause total crop loss if not controlled effectively.

A regional workshop on MLN and the control strategies was organized by CIMMYT and KARI during February 12-14, 2013 in Nairobi, which was attended by some 70 scientists, seed company breeders and managers, and representatives of ministries of agriculture and regulatory authorities in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and the USA. The Workshop led to identification of important action points steps for effectively controlling the disease.

CIMMYT scientists have been working closely with virology experts from USDA-ARS and Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) to develop suitable protocols for testing the responses of maize germplasm against MLN, and to identify promising inbred lines and hybrids with resistance to MLN. During the 2012-2013 crop season, the CIMMYT-KARI team undertook extensive screening of inbred lines, pre-commercial and commercial hybrids in Naivasha and Narok in Kenya, under high natural disease pressure and artificial inoculation, respectively.

A trial featuring 119 commercial maize varieties (released in Kenya) under artificial inoculation during 2012-2013 revealed that as many as 117 varieties were susceptible to MLN. Another set of trials including 335 elite inbred lines, 366 pre-commercial hybrids and 7 commercial hybrids (as checks) under MLN artificial inoculation in Narok, and another set of trials comprising 350 elite inbred lines and 135 pre-commercial hybrids under natural disease pressure in Naivasha, led to identification of some promising CIMMYT inbred lines as well as pre-commercial hybrids showing resistance or moderate resistance. These results offer considerable hope to combat, through breeding efforts, the deadly MLN disease that has severely affected maize harvests and discouraged farmers from growing maize in eastern Africa.

The details of the promising CIMMYT elite inbred lines and pre-commercial hybrids against MLN are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. The results presented in Table 1 are based on evaluation of CIMMYT inbred lines in four independent trials, two under artificial inoculation (Narok) and two under natural disease pressure (Naivasha) during 2012-2013. In each trial, entries were replicated (minimum two), and MLN severity scores (on a 1-5 scale basis) were recorded three or more times during the crop cycle, from the vegetative to the reproductive stage. The highest average MLN severity score (max. MLN score), recorded at any stage during the trial, is presented as representative of a given entry.

The data must be critically assessed and cautiously used by stakeholders and partners. More weight should be given to data from artificially inoculated trials, since trials under natural disease pressure are more liable to ‘disease escapes’ and identification of false positives. Caution must be exercised when using specific lines identified as potentially resistant (R) or moderately resistant (MR), especially when classification is based on data from only one trial (even under artificial inoculation). Please note that in such cases, the responses of the lines need to be validated by CIMMYT through further trials.

CIMMYT is working closely with both public and private sector partners to significantly expand the MLN evaluation network capacity in eastern Africa, and will continue the intensive efforts to identify/develop and deliver new sources of resistance to MLN.

For further information on:

MLN research-for-development efforts undertaken by CIMMYT, please contact: Dr BM Prasanna, Director, Global Maize Program, CIMMYT, Nairobi, Kenya; Email: b.m.prasanna@cgiar.org.

Availability of seed material of the promising lines and pre-commercial hybrids, please contact: Dr Mosisa Regasa (m.regasa@cgiar.org) if your institution is based in eastern Africa, or Dr James Gethi (j.gethi@cgiar.org) if your institution is based in southern Africa or outside eastern and southern Africa.

UPDATE: Promising CIMMYT maize inbreds and pre-commercial hybrids identified against maize lethal necrosis (MLN) in eastern Africa

Maize lethal necrosis (MLN) disease in Kenya and Tanzania: Facts and actions (Download )

KARI-CIMMYT maize lethal necrosis (MLN) screeing facility (1.43 MB)

Maize lethal necrosis: Scientists and key stakeholders discuss strategies as the battle continues

MLN: A farmer’s plea MLN: A farmer’s plea |

Maize lethal necrosis disease: A new challenge Maize lethal necrosis disease: A new challengefor maize scientists in eastern Africa |

Deadly maize disease resurfaces in N. Rift. Business Daily, 31 May 2013.

Fresh viral maize disease worries farmers. Daily Nation, 31 May 2013.

Alert out in Coast over maize disease. Daily Nation, 31 May 2013.

Agricultural extension service staff members in Zambia have been challenged to be the first adopters of metal silos to help promote the technology for effective grain storage. “I implore you, extension workers, to be the first adopters and users of the metal silo technology. As citizens that live side by side with farmers, go and be the first to practice what you will be preaching. You must lead by example,” stated Bert Mushala, the Permanent Secretary, Provincial Administration, Office of the President, Eastern Province, in a speech read on his behalf by his assistant Beenzu Chichuka at the official opening of the Improved Postharvest Management Training Workshop for Extension and Media Personnel held during 27- 28 May 2013 in Chipata, Zambia. “Farmers learn by seeing. Therefore, before they start using the metal silos, they want to see the chief executives, the business executives, extension workers, journalists, and other opinion leaders in the forefront, zealously storing maize in the metal silos,” he added.

Agricultural extension service staff members in Zambia have been challenged to be the first adopters of metal silos to help promote the technology for effective grain storage. “I implore you, extension workers, to be the first adopters and users of the metal silo technology. As citizens that live side by side with farmers, go and be the first to practice what you will be preaching. You must lead by example,” stated Bert Mushala, the Permanent Secretary, Provincial Administration, Office of the President, Eastern Province, in a speech read on his behalf by his assistant Beenzu Chichuka at the official opening of the Improved Postharvest Management Training Workshop for Extension and Media Personnel held during 27- 28 May 2013 in Chipata, Zambia. “Farmers learn by seeing. Therefore, before they start using the metal silos, they want to see the chief executives, the business executives, extension workers, journalists, and other opinion leaders in the forefront, zealously storing maize in the metal silos,” he added.

The purpose of the training was to build technical capacity on hermetic grain storage technologies, such as metal silos and super grain bags, among extension and media staff in the project implementation districts of Chipata and Katete. The workshop intended to create awareness on the importance of grain post-harvest management, help gain insights into different factors affecting post-harvest management, and provide a better understanding of traditional and improved post-harvest technologies and their use in grain loss reduction, summarized Tadele Tefera, CIMMYT entomologist and the Effective Grain Storage for Sustainable Livelihoods of African Farmers Project (EGSP II) coordinator. Ivor Mukuka, EGSP national coordinator for Zambia and ZARI chief agricultural research officer, noted that this was part of the process of sharing information on EGSP as a means of promoting effective grain storage and thus helping smallholder farmers safely keep their grains for longer and sell when the time and price are right.

Reiterating the importance of the technology, Mushala noted that self-sufficiency in food grains in the country does not depend only on increased production and productivity, but also on minimizing losses both in the field and during storage. Over the years, supporting organizations and other partners, including the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, have poured colossal amounts of resources into the production component of the sector. “The resultant improved yield gains, especially in maize, have largely been wasted through post-harvest losses,” regretted Mushala, adding that “this project is therefore unique and outstanding to us in Zambia as it focuses on the comparatively neglected storage aspects. It is the first one of its kind and could not have come at a better time.”

Mushala then reminded the journalists that they had an enormous task of educating the masses on the new form of storage as many citizens, even in urban areas, are engaged in agriculture. “Go and empower the masses with this information so that together, we can reduce on-farm storage losses to zero,” Mushala urged the participants. Eastern Province Agriculture coordinator Obvious Kabinda called for commitment: “You must have confidence and belief in the technology if you are to successfully promote it to others.”

The messages did not get lost on the participants. “I have gained good knowledge of the technology and, like other trainees, will be using it to ensure that farmers are aware of its existence, have access to it, and are able to adopt the metal silos,” said Michelo Lubinda, a producer with the Zambia News and Information Services (ZANIS), confirming the usefulness of the workshop.

Tefera thanked the Zambia Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI) and the Ministry of Agriculture for their commitment in implementing the project in Zambia, and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) for funding the project.

The training was organized by CIMMYT, ZARI, and the Department of Mechanization, Ministry of Agriculture, and facilitated by Tefera, Mukuka, CIMMYT agricultural economist Hugo De Groote, EGSP policy economist Jones Govereh, and senior mechanization specialist Moffat Khosa and principal agricultural engineer Egbet Munganama from the Department of Mechanization Ministry of Agriculture, Zambia.

“Declining water table, deteriorating soil health, labor shortages, increasing energy prices, and more frequent climate extremes are among the major long-term threats to food security in India,” stated ML Jat, CIMMYT senior cropping systems agronomist, at the Stakeholders’ Consultation on Promoting Resilient Diversification Options through Maize and Climate Smart Practices on 20 May 2013 in Karnal, Haryana, India.

About 300 stakeholders from a range of public and private organizations attended the consultation, including representatives from the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), Central Soil Salinity Research Institute (CSSRI), Directorate of Wheat Research (DWR), Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, the Indian Maize Development Association (IMDA), the International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI), the Haryana Agricultural University (HAU), and the State Department of Agriculture, Government of India. After a welcome speech by DK Sharma, CSSRI director, RS Paroda, chairman of the Haryana Farmers Commission at the Government of Haryana and the chief guest of the function, explained the reasons behind the meeting, stressing the criticality of the current situation. “On one hand, we are facing many problems threatening our agricultural system,” he said, “on the other, we are exploring the possibilities of a second Green Revolution for sustainable food and nutritional security in India.” This cannot be achieved without multistakeholder partnerships, as the tasks are numerous: “We need to combine new technologies with active and strategic partnerships, establish an environment in which farmers can easily access markets, and create new business models to make agriculture more attractive to the youth and to women.”

JS Sandhu, agriculture commissioner at the Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, and the event’s guest of honor, commented on climate extremes which caused a decline in food production during 2012- 13. He stressed the importance of technologies helping with adaptation to and mitigation of climate change effects, such as zero tillage, direct seeded rice, or tools like GreenSeeker, but also the need to diversify rice with maize and other economically competitive and more water efficient crops in the north-western part of India. “Maize is the queen of cereals,” added Alok K Sikka, the event’s chair and deputy director general of the Natural Resource Management at ICAR, “but there has been a 66% decline in maize growing areas in Haryana since the Green Revolution in 1966.” To achieve long-term sustainable ecological intensification of farming systems, Sikka added, conservation agriculture is crucial. Accordingly, several new research initiatives have begun at ICAR focusing on natural resource management. “Partnerships and synergies with advanced research institutes like CIMMYT, CRPs MAIZE, WHEAT, and Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), and other research-for-development organizations are critical for impact at scale,” concluded Sikka.

As part of the consultation, panel discussions were held on resilient diversification options through maize (chaired by Sain Dass, IMDA president) and on promoting climate smart practices (chaired by Indu Sharma, DWR director); the discussions were followed by a plenary session chaired by DP Singh (Natural Resource Management expert, Haryana Farmers Commission). The panel discussions reiterated what was said during the presentations and added several new areas of focus, for example the use of information and communication technologies and knowledge networks to provide farmers with real time access to information in an easy-to-understand form.

The event was jointly organized under the aegis of CRPs CCAFS and WHEAT by CIMMYT in collaboration with CSSRI, ICAR, Haryana Farmers Commission, HAU, State Department of Agriculture, Government of Haryana, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India and Farmer Cooperatives of Climate Smart Villages.

Three drought-tolerant maize hybrids performing well in drought-prone areas and tolerant of Malawi’s major maize diseases have been released in Malawi. The new hybrids, said a member of the Agricultural Technology Clearing Committee, will contribute to the subsidy program that has seen Malawi become self-sufficient in maize production and even export surplus maize to neighboring countries. They will also be important in mitigating climate change. “Maize accounts for over 70% of cereal production,” maize commodity team leader Kesbelll Kaonga explained the importance of maize for the country, adding that Malawians consume on average about 300 kg per year.

Three drought-tolerant maize hybrids performing well in drought-prone areas and tolerant of Malawi’s major maize diseases have been released in Malawi. The new hybrids, said a member of the Agricultural Technology Clearing Committee, will contribute to the subsidy program that has seen Malawi become self-sufficient in maize production and even export surplus maize to neighboring countries. They will also be important in mitigating climate change. “Maize accounts for over 70% of cereal production,” maize commodity team leader Kesbelll Kaonga explained the importance of maize for the country, adding that Malawians consume on average about 300 kg per year.

The hybrids, developed under the Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa (DTMA) project by the Malawian Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security and Chitedze Research Station in collaboration with CIMMYT and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), were also tested in farmers’ fields. “The farmers liked them because of the high grain yield, drought tolerance, and flint grains,” Kaonga said, explaining that Malawian farmers prefer flint maize because its grains store better and provide more flour per kilogram compared to dent maize. The new hybrids can yield up to eight tons per hectare under optimum conditions.

The hybrids—Malawi Hybrids 30, 31, and 32—have been allocated to local seed companies that will start seed production during the coming season. Most of the emerging seed companies depend on germplasm from CIMMYT and the national agricultural research systems, as they do not have their own breeding programs. Variety demonstrations and publicity materials are planned to promote seed delivery in collaboration with seed companies and the Chitedze Research Station. The Department of Agricultural Research thanked CIMMYT breeders and seed specialists Peter Setimela, Amsal Tarekegne, John MacRobert, and Cosmos Magorokosho, who worked closely with them to get the hybrids released.

The CRP MAIZE will be hosting a side event on the role of maize in Africa at the Africa Agriculture Science Week (15-20 July) on 16 July in Accra, Ghana. Join us if you can and follow the AASW Blog and #AASW6 on Twitter.

High fertilizer prices are among the major constraints facing maize farmers in Eastern and Southern Africa. “We apply just a little fertilizer, just the way you would apply salt to taste,” says a maize farmer in the Embu County, Kenya. “We lack enough fertilizer for our maize crop,” explains another one during a focus group discussion.

Kenya imports all its fertilizer, which results in high input costs borne by smallholder farmers. As agriculture forms the backbone of Kenya’s economy, the government offers farmers fertilizer at subsidized rates. “The subsidized price of Urea is about US$ 30 per 50kg bag, while without the subsidy it goes for up to US$ 50 per 50kg bag,” said the County’s land development officer Samuel Kibiu. “Despite the subsidy, not all farmers can afford the fertilizer,” he added. But even if they can, they still have to face several other challenges, such as transporting the fertilizer to their farms in Kieni, about 40 kilometers from the collection point in Embu town, after going through an elaborate process of obtaining subsidy receipts from the local agriculture office.

In October 2012, a team from CIMMYT’s Improved Maize for African Soils (IMAS) project, together with the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) and extension workers from the Ministry of Agriculture, visited a group of farmers in the Kieni Division, Embu County. “Fertilizer is essential in Sub-Saharan Africa,’’ says Biswanath Das, IMAS project leader, “but fertilizer use in the region is amongst the lowest in the world, averaging less than 20kg per hectare.” This falls way below the recommended application rates and below average of what farmers apply in Asia and Latin America. “Most smallholder farmers in Africa are extremely risk averse, as the bulk of smallholder production is under rain-fed systems,” says Das. “As a result, farmers are reluctant to invest in expensive inputs such as fertilizer due to unpredictable rainfall.”

Making fertilizer more accessible in Africa has proved extremely difficult and researchers have thus begun searching for other ways to address the issue. The IMAS project is developing new maize varieties that are more efficient at using the small quantities of nitrogen currently applied in smallholder maize production systems in Southern and Eastern Africa. The goal is to develop maize varieties that yield up to 50% more than the existing varieties through better nitrogen use efficiency. The first set of varieties developed through the IMAS breeding pipeline showed promising results during onstation trials and is being tested by farmers in Kieni. “Despite the poor rains, we got good yields,” said Mercy Wawira commenting on the IMAS hybrid she planted on her farm. “We have seen our yields improve with this new variety,” said John Bosco Mugendi who also participated in the IMAS on-farm trial. “This variety is good,” he added. Members of the community were present to help Wawira and Mugendi harvest the maize from the small trial plot. “We hope we shall get this variety again to plant in the next season,” said Obed Nyaga Njamura, agribusiness development officer in Embu’s Kieni Division.

As yield gains observed under managed low-nitrogen stress trials on station are being replicated under farm conditions in the region, IMAS scientists feel encouraged. Together with partners in the national agricultural research systems in Eastern and Southern Africa (KARI and the Agricultural Research Council of South Africa, ARC) and Pioneer Hi-Bred in the USA, IMAS is developing nitrogen use efficient varieties to benefit smallholder maize farmers in Africa. “We broker technology through these partnerships. We also build capacity through the comparative advantage in the different institutions,” said KARI’s director Ephraim Mukisira.

Covering 2,400 km, a multinational team toured Drought Tolerant Maize in Africa (DTMA) trial and demonstration plots in Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe from 21–30 April in a traveling workshop that combined peer learning and project monitoring and evaluation. The team of 17 was made up of breeders from the national programs, DTMA scientists, and DTMA Advisory Board Chair Dave Westphal. Participants had the opportunity to compare notes, gain new knowledge based on the experiences of colleagues in other countries, and gauge themselves against their peers based on practical, real-life results. “Having a diverse group like this is very educational,” said DTMA Seed Systems Objective Leader John MacRobert.

Covering 2,400 km, a multinational team toured Drought Tolerant Maize in Africa (DTMA) trial and demonstration plots in Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe from 21–30 April in a traveling workshop that combined peer learning and project monitoring and evaluation. The team of 17 was made up of breeders from the national programs, DTMA scientists, and DTMA Advisory Board Chair Dave Westphal. Participants had the opportunity to compare notes, gain new knowledge based on the experiences of colleagues in other countries, and gauge themselves against their peers based on practical, real-life results. “Having a diverse group like this is very educational,” said DTMA Seed Systems Objective Leader John MacRobert.

DTMA addresses a real need in the region: “Drought is part and parcel of our farming systems,” said Zamseed veteran breeder Verma Bhoola when he hosted the team at the company’s farm. “Over 90% of maize grown in Zambia is rainfed, so prone to drought,” he said, emphasizing the importance of breeding for drought tolerance not only in Zambia but also in the rest of Africa, where most maize farming depends on rain patterns that are increasingly unpredictable as a result of climate change. “Twenty-five percent of maize production in Africa is threatened by frequent drought, while 40% is affected by occasional drought,” said DTMA project leader Tsedeke Abate during a feedback session at the end of the workshop.

The project is making significant strides. “We are on track in terms of overall production of drought-tolerant maize seed,” said Abate. More than 100 varieties have been released in 13 countries. “Zimbabwe is leading in seed production, with over 7,000 metric tons of drought-tolerant seeds produced by the end of 2012,” he said.

The tour ended with awards for the top-performing teams in breeding and dissemination. Malawi won top honors in both categories, for the trial plots at the research station and a well-managed demonstration plot in Mkanda Village, on the outskirts of Lilongwe, run by the Vibrant Mkanda Women’s Group. “This really demonstrates what DTMA is doing in partnership with the seed companies and national programs,” said Westphal. DTMA aims to produce and market 70,000 tons of seed annually by 2016.

The fourth confined field trial of MON87460, a genetically modified maize variety developed to tolerate moderate drought, recently concluded at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) in Kiboko with promising results.

The fourth confined field trial of MON87460, a genetically modified maize variety developed to tolerate moderate drought, recently concluded at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) in Kiboko with promising results.

The Water Efficient Maize for Africa (WEMA) project has been conducting field trials of MON87460 since 2010. The most recent trial was planted on 28 November 2012 and harvested on 16 April 2013. Throughout the season, the genetically modified plants outperformed those without the drought-tolerance-enhancing gene, including commercial checks.

This was even more evident at harvest, with ears from the genetically modified plants looking superior to the conventional checks. Charles Kariuki, center director at KARI-Katumani, who was present during the harvesting, was particularly impressed with the performance of the WEMA 18, 36, 41, 50, and 55 entries. “From these, we should be able to generate high quality data to back these impressive performances,” he said. Kariuki urged the project to nominate the conventional entries (without the MON87460 gene), that were also tested in the trials and performed very well, to the Kenya National Performance Trials to fast-track their commercial release.

Murenga Mwimali, WEMA’s national coordinator for Kenya, was looking forward to the outcomes of the data analysis to ascertain this yield performance in detail, comparing the performance against those without the gene and the commercial checks: “This will enable us to make informed conclusions on the potential benefits of MON87460.” Representatives from the regulatory authorities—the Kenya National Biosafety Authority (NBA) and the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS)—also lauded the WEMA team for their good confined field trial management.

The day before the harvest, required training on regulatory compliance was conducted for everyone expected to participate in the harvest. The training covered management requirements and standard operating procedures for confined field trials as well as biosafety requirements for planting, harvesting, and post-harvest monitoring. The 46 participants were drawn from WEMA partner institutions (CIMMYT, African Agricultural Technology Foundation, KARI, and Monsanto), as well as the Ministry of Agriculture, KEPHIS, and NBA.

Jane Otadoh, assistant director for biotechnology in the Ministry of Agriculture, emphasized the importance of training to enable staff to effectively handle confined field trials. “There is lack of awareness, information, and knowledge on biotechnology in Kenya, and more so on confined field trial operations, requirements, and regulations. This training is to help you understand the process, the role of scientists, the regulatory process, and the regulators,” she said. She reiterated the ministry’s support for technology that boosts agricultural productivity.

James Karanja of the KARI-Katumani biotechnology program took participants through the standard operating procedures for harvesting confined field trials. Julia Njagi, biosafety officer at NBA, noted that staff training was critical to ensure compliance with biosafety regulations while performing the trials. As part of confined field trial management and regulatory compliance, all harvested materials including grains had to be destroyed by burning and burying, to avoid unintended release of genetically modified materials into the environment.

Eveline Shitabule, an inspector with KEPHIS, noted that training helped the participants to understand and follow instructions to ensure compliance. Having competent and well-trained personnel is one of the three pillars of compliance, the other two being a secure facility and records that are accessible and understandable.

Eveline Shitabule, an inspector with KEPHIS, noted that training helped the participants to understand and follow instructions to ensure compliance. Having competent and well-trained personnel is one of the three pillars of compliance, the other two being a secure facility and records that are accessible and understandable.

Participants said they gained valuable knowledge during the workshop that improved their ability to work on confined field trials.

“This project is a rare example of a public-private partnership capable of delivering products to farmers,” said Mike Robinson of the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA) at the Affordable, Accessible, Asian (AAA) Drought Tolerant Maize Annual Meeting organized by CIMMYT-Asia at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) campus during 20-21 May 2013.

“This project is a rare example of a public-private partnership capable of delivering products to farmers,” said Mike Robinson of the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA) at the Affordable, Accessible, Asian (AAA) Drought Tolerant Maize Annual Meeting organized by CIMMYT-Asia at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) campus during 20-21 May 2013.

Twenty-seven participants from CIMMYT, Syngenta, and national partners from Indonesia and Vietnam were welcomed by B.M. Prasanna, CIMMYT Global Maize Program director, who elaborated CIMMYT-Asia senior maize breeder B.S. Vivek presented a graphical overview of the project covering its objectives and discussing the progress achieved in 2012. Syngenta’s Naveen Sharma, Srinivasu Bolisetty, and Pathayya Ravindra then reported on the progress made in product development and product testing under managed and targeted stress environments. Future breeding plans were also discussed. Ian Barker, SFSA, discussed plans for delivering AAA products to farmers, Prasanna explained issues related to germplasm export and remedial strategies, and Manuel Logrono of Syngenta elaborated on the plans for testing and seed production. At the end of the first day, Vivek provided an overview of the association mapping project, and CIMMYT-Asia senior maize physiologist P.H. Zaidi gave a talk on the progress in root phenotyping.

The second day began with a visit to the rhizotronics facility at ICRISAT, followed by detailed presentations on genotyping and genome-wide association study (GWAS) analysis by CIMMYT Asia maize molecular breeder Raman Babu, and the progress on Syngenta’s side by Aparna Padalkar. Vivek then took over the stage again to compare the gains made by markers viza- viz conventional approach when talking about CIMMYT’s progress with Marker Assisted Recurrent Selection (MARS) and Genome Wide Selection (GWS). Hu Hung from the Vietnamese National Maize Research Institute and Muhammad Azrai from the Indonesian Cereals Research Institute then reported on the progress made in Vietnam and Indonesia, respectively.

After comparing CIMMYT’s and Syngenta’s approaches to drought phenotyping and the merits and demerits of biparental versus multiparental approaches to GWS, CIMMYT-Asia maize breeder Kartik Krothapalli concluded the meeting with a summary of the action plans discussed during the meeting.