Men’s roles and attitudes are key to gender progress, says CIMMYT gender specialist

Gender research and outreach should engage men more effectively, according to Paula Kantor, CIMMYT gender and development specialist who is leading an ambitious new project to empower and improve the livelihoods of women, men and youth in wheat-based systems of Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Pakistan.

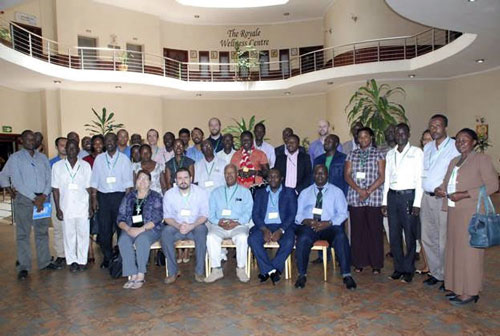

“Farming takes place in socially complex environments, involving individual women and men who are embedded in households, local culture and communities, and value chains — all of which are colored by expectations of women’s and men’s appropriate behaviors,” said Kantor, who gave a brownbag presentation on the project to an audience of more than 100 scientists and other staff and visitors at El Batán on 20 February. “We tend to focus on women in our work and can inadvertently end up alienating men, when they could be supporters if we explained what we’re doing and that, in the end, the aim is for everyone to progress and benefit.”

Funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, the new project will include 14 village case studies across the three countries. It is part of a global initiative involving 13 CGIAR research programs (CRPs), including the CIMMYT-led MAIZE and WHEAT. Participants in the global project will carry out 140 case studies in 29 countries; WHEAT and MAIZE together will conduct 70 studies in 13 countries. Kantor and Lone Badstue, CIMMYT’s strategic leader for gender research, are members of the Executive Committee coordinating the global initiative, along with Gordon Prain of CIP-led Roots, Tubers and Bananas Program, and Amare Tegbaru of the IITA-led Program on Integrated Systems for the Humid Tropics.

“The cross-CRP gender research initiative is of unprecedented scope,” said Kantor. “For WHEAT, CIMMYT, and partners, understanding more clearly how gendered expectations affect agricultural innovation outcomes and opportunities can give all of our research more ‘ooomph’, helping social and biophysical scientists to work together better to design and conduct socially and technically robust agricultural R4D, and in the end achieve greater adoption and impact.”

To that end, outcomes will include joint interpretation of results with CRP colleagues and national stakeholders, scientific papers, policy engagement and guidelines for integrating gender in wheat research-for-development, according to Kantor. “The research itself is important, but can’t sit on a shelf,” she explained. “We will devise ways to communicate it effectively to partners in CGIAR and elsewhere.”

Another, longer-term goal is to question and unlock gender constraints to agricultural innovation, in partnership with communities. Kantor said that male migration and urbanization are driving fundamental, global changes in gender dynamics, but institutional structures and policies must keep pace. “The increase in de facto female-headed households in South Asia, for example, would imply that there are more opportunities for women in agriculture,” she explained, “but there is resistance, and particularly from institutions like extension services and banks which have not evolved in ways that support and foster the empowerment of those women.”

“To reach a tipping point on this, CGIAR and the CGIAR Research Programs need to work with unusual partners — individuals and groups with a presence in communities and policy circles and expertise in fostering social change,” said Kantor. “Hopefully, the case studies in the global project will help us identify openings and partners to facilitate some of that change.”

Kantor has more than 15 years of experience in research on gender relations and empowerment in economic development, microcredit, rural and urban livelihoods, and informal labor markets, often in challenging settings. She served four years as Director and Manager of the gender and livelihoods research portfolios at the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) in Kabul. “AREU has influenced policy, for example, through its work on governance structures at the provincial and district levels,” Kantor said. “They will be a partner in the Afghan study.”

She added that working well in challenging contexts requires a complex combination of openness about study aims and content in communities, sensitivity and respect for relationships and protocol, careful arrangements for logistics and safety, diverse and well-trained study teams and being flexible and responsive. “Reflections on doing gender research in these contexts will likely be an output of the study.”

After her first month at CIMMYT, Kantor, who will be based in Islamabad, Pakistan, said she felt welcome and happy. “My impression is that people here are very committed to what they do and that research is really a priority. I also sense real movement and buy-in on the gender front. An example is the fact that, of all the proposals that could’ve been put forward for funding from BMZ, the organization chose one on gender. That’s big.”

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – A social media crowd sourcing campaign initiated to celebrate the achievements of women has led to more than a dozen published blog story contributions about women in the maize and wheat sectors.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – A social media crowd sourcing campaign initiated to celebrate the achievements of women has led to more than a dozen published blog story contributions about women in the maize and wheat sectors.

In 2014, the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro) program expanded its rural development and innovation networks to 10 Mexican regions through 50 research platforms and 233 demonstration modules of MasAgro technologies and sustainable agronomic practices.

In 2014, the Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture (MasAgro) program expanded its rural development and innovation networks to 10 Mexican regions through 50 research platforms and 233 demonstration modules of MasAgro technologies and sustainable agronomic practices.