Breaking Ground: Gokul Paudel finds the best on-farm practices for South Asia

Gokul Paudel is an agricultural economist working to streamline farming practices in South Asia. He seeks to understand, learn from and improve the efficiency of on-farm management practices in a vast variety of ways. Although he joined the International Improvement Center for Wheat and Maize (CIMMYT) right after university, Paudel’s on-farm education started long before his formal courses.

“I was born in a rural village in Baglung district, in the mid-hills of Nepal. My parents worked on a small farm, holding less than half a hectare of land,” he says. “When I was a kid, I remember hearing that even though Nepal is an agricultural country, we still have a lot of food insecurity, malnutrition and children who suffer from stunting.”

“I would ask: How is Nepal an agricultural country, yet we suffer from food insecurity and food-related problems? This question is what inspired me to go to an agricultural university.”

Paudel attended Tribhuvan University in Nepal, and through his coursework, he learned about plant breeding, genetic improvement and how Norman Borlaug brought the first Green Revolution to South Asia. “After completing my undergraduate and post-graduate studies, I realized that CIMMYT is the one organization that contributes the most to improving food security and crop productivity in developing countries, where farmers livelihoods are always dependent on agriculture,” he explains.

Approaching the paradox

Paudel is right about the agriculture and food paradox of his home country. Almost two thirds of Nepal’s population is engaged in agricultural production, yet the country still has shockingly high numbers in terms of food insecurity and nutritional deficiency. Furthermore, widespread dissemination of unsustainable agronomic practices, like the use of heavy-tilling machinery, present similar consequences across South Asia.

If research and data support the claim that conservation agriculture substantially improves crop yields, then why is the adoption of these practices so low? That is exactly what Paudel seeks to understand. “I want to help improve the food security of the country,” he explains. “That’s why I joined the agricultural sector.”

Paudel joined CIMMYT in 2011 to work with the Socioeconomics Program (SEP) and the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), providing regional support across Bangladesh, India and Nepal.

His work is diverse. Paudel goes beyond finding out which technological innovations increase on-farm yield and profit, because success on research plots does not always translate to success on smallholder fields. He works closely with farmers and policy makers, using surveys and high-tech analytical tools such as machine learning and data mining to learn about what actually happens on farmers’ plots to impact productivity.

A growing future for conservation agriculture

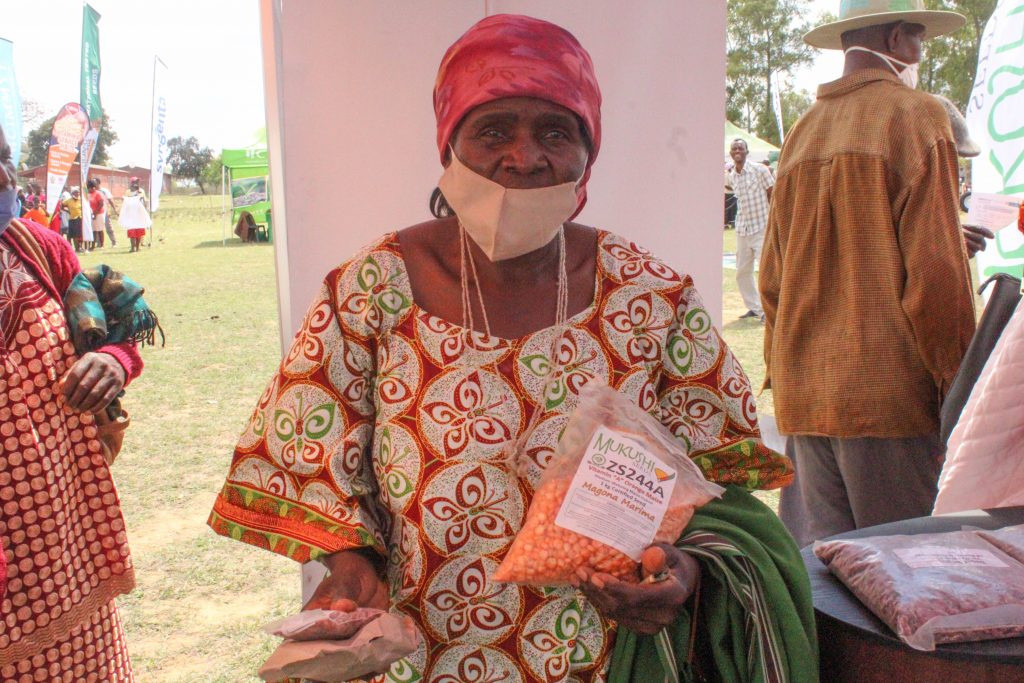

Over the last two decades, the development of environmentally sustainable and financially appealing farming technologies through conservation agriculture has become a key topic of agronomic research in South Asia.

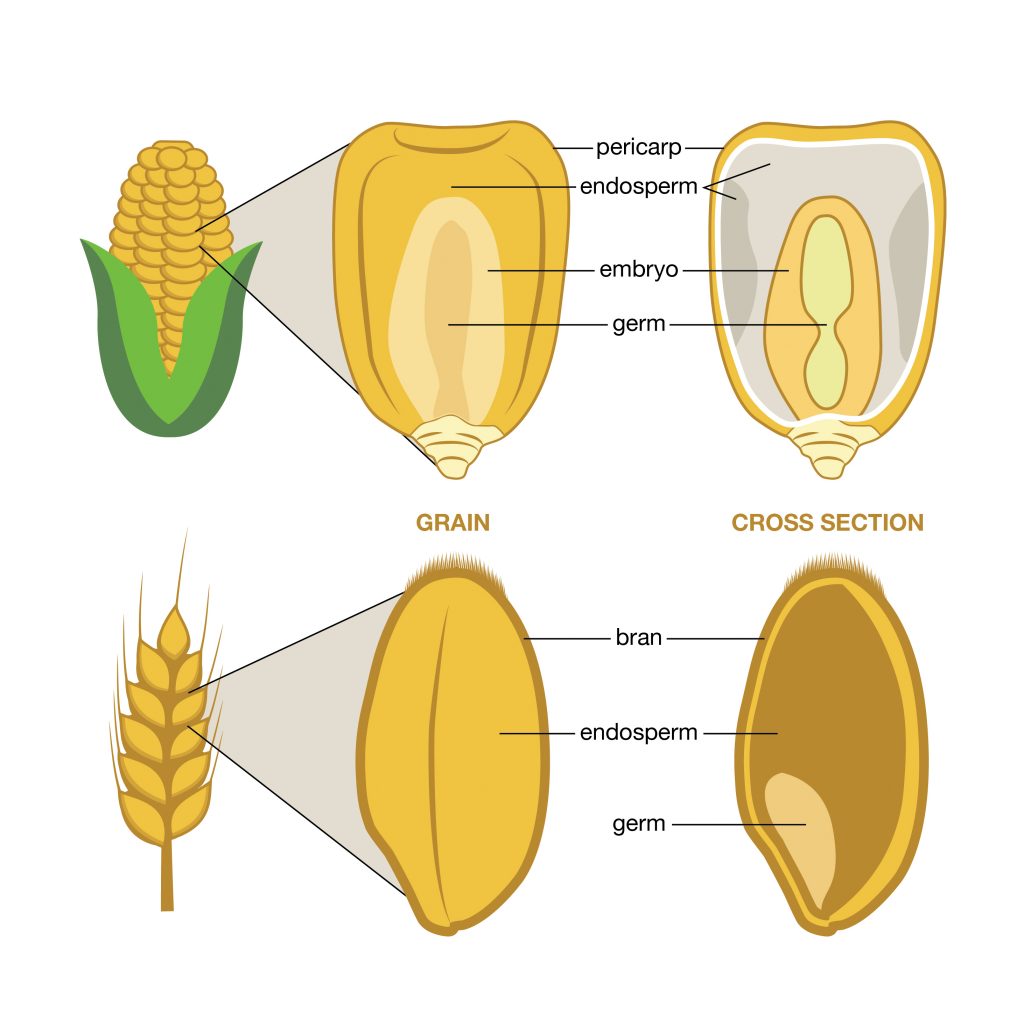

“Conservation agriculture is based on three principles: minimum disturbance of the soil structure, cover crop and crop rotation, especially with legumes,” Paudel explains.

Leaving the soil undisturbed through zero-till farming increases water infiltration, holds soil moisture and helps to prevent topsoil erosion. Namely, zero-till farming has been identified as one of the most transformative innovations in conservation agriculture, showing the potential to improve farming communities’ ability to mitigate the challenges of climate change while also improving crop yields.

Still, the diffusion rate of zero-tillage has remained low. Right now, Paudel’s team is looking at a range of factors — such as farmers’ willingness to pay, actual demand for new technologies, intensification under input constraints, gender-disaggregated preferences and the scale-appropriateness of mechanization — to better understand the low adoption rates and to find a way to close the gap.

Can farm mechanization ease South Asia’s labor shortage?

In South Asia, understanding local contexts is crucial to streamlining farm mechanization. In recent years, many men have left their agricultural jobs in search of better opportunities in the Gulf countries and this recent phenomenon of labor out-migration has left women to take up more farming tasks.

“Women are responsible for taking care of the farm, household and raising their children,” says Paudel. “Since rural out-migration has increased, they have been burdened by the added responsibility of farm work and labor scarcity. This means that on-farm labor wages are rising, exacerbating the cost of production.”

The introduction of farm machinery, such as reapers and mini-tillers, can ease the physical and financial burden of the labor shortage. “Gender-responsive farm mechanization would not only save [women’s] time and efforts, but also empower them through skills enhancement and farm management,” says Paudel. However, he explains, measures must be taken to ensure that women actually feel comfortable adopting these technologies, which have traditionally been held in the male domain.

From farm-tech to high-tech

Right now, amidst the global lockdown due to COVID-19, Paudel’s field activities are highly restricted. However, he is capitalizing on an opportunity to assess years’ worth of data on on-farm crop production practices, collected from across Bangladesh, India and Nepal.

“We are analyzing this data-set using novel approaches, like machine learning, to understand what drives productivity in farmers’ fields and what to prioritize, for our efforts and for the farmers,” he explains.

Although there are many different aspects of his work, from data collection and synthesis to analysis, Paudel’s favorite part of the job is when his team finds the right, long-lasting solution to farmers’ production-related problems.

“There’s a multidimensional aspect to it, but all of these solutions affect the farmer’s livelihood directly. Productivity is directly related to their food security, income and rural livelihoods.”

A changing landscape

About 160 km away from where he lives now, Paudel’s parents still own the farm he grew up on — though they no longer work on it themselves. They are proud to hear that his work has a direct impact on communities like theirs throughout the country.

“Every day, new problems are appearing due to climate change — problems of drought, flooding and disease outbreak. Though it’s not good news, it motivates me to continue the work that I’m doing,” says Paudel. “The most fascinating thing about working at CIMMYT is that we have a team of multidisciplinary scientists working together with the common goal of sustainably intensifying the agricultural systems in the developing world.”