CIMMYT E-News, vol 5 no. 10, October 2008

Senior policy makers from sub-Saharan Africa have recently made recommendations for policy actions to reform operations in the maize seed sector. At stake is better access for millions of small-scale farmers to affordable, quality seed of maize, the region’s food staple. CIMMYT is closely involved.

In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

A recent CIMMYT study found that restrictive national policies, lack of credit opportunities, inadequate seed production capacities, insufficient numbers of recently released public sector varieties, and challenging marketing situations were the main reasons why maize seed sector growth is slow in many African countries. Worse, this situation contributes significantly to Africa’s poor food security and farm incomes.

“The good news is that we have today four times more seed companies than ten years ago and they have increased seed provision from 26% to 35% of the total planted maize area,” says CIMMYT socioeconomist Augustine Langyintuo. “Yet there is still a significant, unmet demand for seed, and this underscores the need for new policies that support efficient seed production, processing, and marketing.”

In 2007 Langyintuo led the above-mentioned study to characterize seed providers and bottlenecks to seed supplies in eastern and southern Africa. A total of 117 representatives from seed companies, national research programs, and CBOs/NGOs participated, and information was gathered on the seed sectors in Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

In July 2008, more than 60 senior policy makers from agriculture ministries, private seed companies, seed trade associations, and regional trade blocs from 13 sub-Saharan African countries met in Nairobi, Kenya and recommended ways to improve farmers’ access to seed of improved drought tolerant maize varieties through specific policy actions to enhance the production, release, and marketing of these varieties. They agreed with the findings of the 2007 seed sector study.

Understanding the hurdles

The main findings were that investment capital requirements and a shortage of qualified staff hinder the growth of small, local seed companies that have emerged over the past decade, according to Langyintuo. “The costs of setting up and running an office, recruiting and retaining qualified personnel, and procuring and operating production, processing, and storage facilities are beyond what many local businesses can afford, and access to operational credit is limited or nil,” he says.

Up to 60% of a seed company’s operational budget goes into seed production. Seed companies, therefore, need affordable credit over the mid-to-long term to produce enough seed to meet farmers’ needs. Marketing seed is also costly. “Most companies rely on third-party agents such as agro-dealers, large retail stores, NGOs, or the government to retail most of their seed,” says Langyintuo. “The majority of the agro-dealers lack funds to purchase seed, and so must take it on consignment, forcing companies to retrieve unsold seed at cost. The dealers are normally not knowledgeable enough about the seed they sell to promote it effectively, and some of them have also been known to adulterate seed with mere grain.”

Other hurdles identified include cumbersome varietal release, registration, and seed certification regulations, as well as a weak producer base, slow access to the best germplasm, uncompetitive prices in local grain markets, low adoption rates of improved varieties, restrictions on cross-border trade in seed, and poor infrastructure (such as bad roads and inadequate storage facilities).

Policy actions needed

To get farmers the seed they want will involve a range of players in the maize seed sector and calls for specific policy actions. Participants in the July 2008 meeting identified ways in which governments and international centers like CIMMYT and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) can assist and support current seed companies to improve their seed outputs and profits.

“The government is supporting the maize seed sector through initiatives such as increasing investments in agricultural research and extension, training of agro-dealers, and developing the National Seed Industry Policy,” confirms Kenya’s Assistant Minister of Agriculture, Japheth Mbiuki.

“Seed companies would benefit from access to a wider range of improved maize varieties, good seed production sites, affordable inputs, and training in effective business practices,” adds Langyintuo. CIMMYT normally distributes its experimental varieties freely to everyone, but granting companies some degree of exclusivity in their use would facilitate branding and promote sales. This would have to be tailored to specific country and company contexts, according to Langyintuo.

Maize seed without borders

No country is an island, and with increasing regional integration of economies around the world, it makes sense that the region should move as one in developing its maize seed sector. Regional trade blocs such as the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) are key. “Specific actions and commitments by national governments include dedicating increased funds (at least 10% of their national budgets) for agricultural development and harmonization of regional seed regulations,” says Ambassador Nagla El-Hussainy, COMESA Assistant Secretary General. “This will improve rates of variety release, lower costs in dealing with regulatory authorities, increase trade in seed of improved varieties and, ultimately, adoption by farmers.” In East Africa, for instance, the national seed policies of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania are at various stages of development and are set to be harmonized soon.

“Effective trade and risk management strategies that buffer seed supply within countries are needed to stabilize and increase maize production in the region,” says Marianne Bänziger, CIMMYT Global Maize Program Director. “These will mitigate the impact of drought and national production fluctuations, which are some of the harsh realities that farmers and consumers face.”

“Where applicable, carrying out the distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) tests alongside national performance trials (NPT) could speed up varietal releases,” adds Langyintuo. “Farmers’ awareness of the usefulness and availability of new varieties can be raised through improved extension message delivery, widespread demonstrations, and better retail networks.”

According to Richard Amoussou, an Assistant Secretary in the Ministry of Agriculture in Benin: “The links between (community-based) seed producers and seed companies should be strengthened through contracts. This will ensure that quality seed is produced and sold to seed companies, who must finally distribute the seed to the farmers, thus improving their access.”

“Streamlining the seed sector will directly benefit the productivity and incomes of small-scale farmers and result in more and more affordable food for consumers – significant in the current global food crisis,” concludes Bänziger. She says this is crucial, given the twin challenges of the global food price crisis and more frequent droughts due to climate change.

For more information: Augustine Langyintuo, socioeconomist (a.langyintuo@cgiar.org)

Remembering the life of Dr. Robert Havener, former Director General of CIMMYT.

Remembering the life of Dr. Robert Havener, former Director General of CIMMYT. On 12 March 2004, CIMMYT took a modest but historic step in the development of drought tolerant wheat, when a small trial plot was sown to genetically modified (transgenic) wheat in a screenhouse at the Center’s headquarters in Texcoco, Mexico. This is the first time that transgenic wheat has been planted under field-like conditions in Mexico, and rigorous biosafety procedures are being followed.

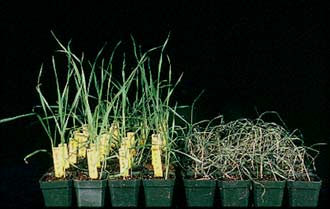

On 12 March 2004, CIMMYT took a modest but historic step in the development of drought tolerant wheat, when a small trial plot was sown to genetically modified (transgenic) wheat in a screenhouse at the Center’s headquarters in Texcoco, Mexico. This is the first time that transgenic wheat has been planted under field-like conditions in Mexico, and rigorous biosafety procedures are being followed.

In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

Breeding knowledge combined with cutting-edge laboratory analysis will produce maize rich in vital nutrients.

Breeding knowledge combined with cutting-edge laboratory analysis will produce maize rich in vital nutrients.

Global Rust Initiative tackles a clearly present danger.

Global Rust Initiative tackles a clearly present danger.

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences  This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance.

This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance. CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.

CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.

Every 1990-term US dollar invested in CIMMYT’s wheat genetic improvement over the past 40 years has generated at least 27 times its value in benefits from leaf rust resistance breeding in spring bread wheat alone, according to a recent CIMMYT study entitled “The Economic Impact in Developing Countries of Leaf Rust Resistance Breeding in CIMMYT–Related Spring Bread Wheat.”

Every 1990-term US dollar invested in CIMMYT’s wheat genetic improvement over the past 40 years has generated at least 27 times its value in benefits from leaf rust resistance breeding in spring bread wheat alone, according to a recent CIMMYT study entitled “The Economic Impact in Developing Countries of Leaf Rust Resistance Breeding in CIMMYT–Related Spring Bread Wheat.” CIMMYT has entered into a collaborative research program to increase household and regional food security and incomes, as well as economic development, in eastern and southern Africa, through improved productivity from more resilient and sustainable maize-legume farming systems. Known as “Sustainable intensification of maize-legume cropping systems for food security in eastern and southern Africa” (SIMLESA), the program aims to increase productivity by 30% and reduce downside risk by 30% within a decade for at least 0.5 million farm households in those countries, with spill-over benefits throughout the region. In addition to CIMMYT, the program involves the

CIMMYT has entered into a collaborative research program to increase household and regional food security and incomes, as well as economic development, in eastern and southern Africa, through improved productivity from more resilient and sustainable maize-legume farming systems. Known as “Sustainable intensification of maize-legume cropping systems for food security in eastern and southern Africa” (SIMLESA), the program aims to increase productivity by 30% and reduce downside risk by 30% within a decade for at least 0.5 million farm households in those countries, with spill-over benefits throughout the region. In addition to CIMMYT, the program involves the Many of us often underestimate the importance of water on our daily lives – that is until the taps run out of water or the well runs dry. For farmers, their lives are intimately connected to the abundance or lack of water. Many farmers in the developing world produce crops which are dependent on unpredictable patterns of rainfall. For these farmers, water is not only a resource, but truly the source of life.

Many of us often underestimate the importance of water on our daily lives – that is until the taps run out of water or the well runs dry. For farmers, their lives are intimately connected to the abundance or lack of water. Many farmers in the developing world produce crops which are dependent on unpredictable patterns of rainfall. For these farmers, water is not only a resource, but truly the source of life. Seed is the lifeblood of CIMMYT research and partnerships. Behind the scenes at CIMMYT, many thousands of seeds are on the move. Constantly arriving and departing as seed is shared with partners, they may journey through rigorous health testing in the laboratory, planting in the soils of the center’s research stations, or storage in the icy vaults of the germplasm bank.

Seed is the lifeblood of CIMMYT research and partnerships. Behind the scenes at CIMMYT, many thousands of seeds are on the move. Constantly arriving and departing as seed is shared with partners, they may journey through rigorous health testing in the laboratory, planting in the soils of the center’s research stations, or storage in the icy vaults of the germplasm bank.