A boost for maize in the State of Mexico

CIMMYT E-News, vol 5 no. 2, February 2008

The State of Mexico borders the country’s capital, Mexico City—a potential market of nearly 20 million inhabitants—but farmers there have struggled to make a profit growing maize. CIMMYT is working to help them, as part of a new partnership between the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Mexican Agriculture Secretariat (SAGARPA).

The State of Mexico borders the country’s capital, Mexico City—a potential market of nearly 20 million inhabitants—but farmers there have struggled to make a profit growing maize. CIMMYT is working to help them, as part of a new partnership between the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Mexican Agriculture Secretariat (SAGARPA).

A mountainous entity in the geographical and cultural center of Mexico, the State of Mexico occupies what many would consider an envious position: it surrounds the country’s vibrant and populous capital, Mexico City, whose 18 million-plus population represents an attractive market for goods and services. Industries dominate the state economy, but many inhabitants outside urban areas practice farming, either to supplement their incomes or, in fewer cases, as their chief livelihood. Most of the state’s farmers have grown maize at one time or another, but few have made a profit on the crop, despite their proximity to a megalopolis.

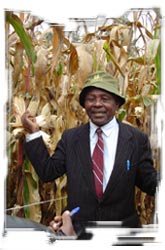

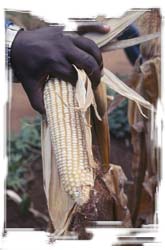

Years of low prices, until recently, for maize grain have discouraged farmers from investing in advanced practices or new varieties. “The state of Mexico accounts for ten percent of national maize production, but improved varieties occupy little more than a tenth of its maize area,” says CIMMYT maize researcher Silverio García. “And nearly all the maize they produce is white grained and ideal for local foods, but fails to meet market standards for large-scale, commercial tortilla production, feed or industrial uses.”

Years of low prices, until recently, for maize grain have discouraged farmers from investing in advanced practices or new varieties. “The state of Mexico accounts for ten percent of national maize production, but improved varieties occupy little more than a tenth of its maize area,” says CIMMYT maize researcher Silverio García. “And nearly all the maize they produce is white grained and ideal for local foods, but fails to meet market standards for large-scale, commercial tortilla production, feed or industrial uses.”

The state of maize

As part of a project launched in 2007 between the USDA and SAGARPA, CIMMYT is working with counterparts in the State of Mexico to increase the productivity and profitability of maize farming. Aims include a broad characterization of maize varieties—both local and improved—for traits of market value; breeding for market requirements; farmer-participatory improvement and testing of varieties; and food technology and nutrition research to guide the project and demonstrate potential impact.

“The focus is on value-added blue, white, and purple maize for food,” says CIMMYT maize breeder and project leader, Gary Atlin. “But partly in response to declining supplies and rising world prices of maize—driven at least in part by the biofuels boom in the USA—farmers are increasingly interested in yellow maize, and participants are developing and testing yellow grain maize suited for feed and industrial markets.”

Atlin and Garcia recently led a workshop of 11 maize scientists from the Mexican National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture, and Livestock Research (INIFAP), Mexico State’s Institute of Agriculture, Livestock, Water, and Forestry Research and Training (ICAMEX), the Colegio de Postgraduados (a graduate-level agricultural research and learning institution), and CIMMYT to plan project activities. Participants contributed detailed information on varieties grown in the state, agreed on common software for managing and analyzing data from trials, and discussed ways to foster farmer participation.

Atlin and Garcia recently led a workshop of 11 maize scientists from the Mexican National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture, and Livestock Research (INIFAP), Mexico State’s Institute of Agriculture, Livestock, Water, and Forestry Research and Training (ICAMEX), the Colegio de Postgraduados (a graduate-level agricultural research and learning institution), and CIMMYT to plan project activities. Participants contributed detailed information on varieties grown in the state, agreed on common software for managing and analyzing data from trials, and discussed ways to foster farmer participation.

Efforts are building on prior work by CIMMYT in Mexico to promote adoption of improved varieties in poorer regions, through crossing local varieties and improved populations to improve farmer-identified traits lacking in their varieties. CIMMYT has also worked with Mexican breeders to develop improved, yellow-grain varieties for several environments, including the Mexican highlands.

“We’re very excited about this project,” says García. “Trials in 2008 will involve experimental varieties that are crosses between improved and local materials, pre-commercial varieties in 20 or more environments in the state, and 40 on-farm demonstrations of commercially-available white and yellow hybrids to get farmers’ feedback.”

For information: Silverio García Lara, maize breeder (s.garcia@cgiar.org)

They often have few options other than to obtain their food and income from agriculture. Achieving food security is the incentive for many to allocate a disproportionately large part of their land to maize, leaving little area to other crops such as legumes or cash crops. Human malnutrition and soil degradation are frequent and few escape the “poverty trap.”

They often have few options other than to obtain their food and income from agriculture. Achieving food security is the incentive for many to allocate a disproportionately large part of their land to maize, leaving little area to other crops such as legumes or cash crops. Human malnutrition and soil degradation are frequent and few escape the “poverty trap.” The demand for maize in Asia is expected to skyrocket in the next two decades, driven primarily by its use for animal feed. In the uplands of seven Asian countries, however, demand is also increasing in the farming households who eat the maize crops they grow. CIMMYT and the

The demand for maize in Asia is expected to skyrocket in the next two decades, driven primarily by its use for animal feed. In the uplands of seven Asian countries, however, demand is also increasing in the farming households who eat the maize crops they grow. CIMMYT and the

African maize farmers who will grow transgenic maize varieties resistant to one of the crop’s most damaging pests—the maize stem borer—learn that to keep borers at bay, some must survive.

African maize farmers who will grow transgenic maize varieties resistant to one of the crop’s most damaging pests—the maize stem borer—learn that to keep borers at bay, some must survive.

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Centuries ago, Spanish monks brought wheat to Mexico to use in Roman Catholic religious ceremonies. The genetic heritage of some of these “sacramental wheats” lives on in farmers’ fields. CIMMYT researchers have led the way in collecting and characterizing these first wheats, preserving their biodiversity and using them as sources of traits like disease resistance and drought tolerance.

Centuries ago, Spanish monks brought wheat to Mexico to use in Roman Catholic religious ceremonies. The genetic heritage of some of these “sacramental wheats” lives on in farmers’ fields. CIMMYT researchers have led the way in collecting and characterizing these first wheats, preserving their biodiversity and using them as sources of traits like disease resistance and drought tolerance.

CIMMYT’s partnerships on maize in eastern Africa hark back to the 1960s, when the center was launched. Formal networking since that time with researchers and extension workers, policy makers, non-government organizations, seed companies, millers, and farmers have culminated in successful breeding and dissemination teams and promising new varieties rated highly by farmers. Awards to teams in Tanzania and Ethiopia recently highlighted the value of these partnerships.

CIMMYT’s partnerships on maize in eastern Africa hark back to the 1960s, when the center was launched. Formal networking since that time with researchers and extension workers, policy makers, non-government organizations, seed companies, millers, and farmers have culminated in successful breeding and dissemination teams and promising new varieties rated highly by farmers. Awards to teams in Tanzania and Ethiopia recently highlighted the value of these partnerships. Some of the poorest and most disadvantaged wheat farmers live in areas with less than 350 mm annual rainfall and their livelihoods often depend solely on income from wheat production. Moreover, in these areas wheat is a staple food, providing around half the daily caloric requirement, and also constitutes an important source of fodder for livestock.

Some of the poorest and most disadvantaged wheat farmers live in areas with less than 350 mm annual rainfall and their livelihoods often depend solely on income from wheat production. Moreover, in these areas wheat is a staple food, providing around half the daily caloric requirement, and also constitutes an important source of fodder for livestock. Farmers of the village of Kathaka Kaome in Embu district near Mount Kenya are saying that quality protein maize (QPM) is as nutritious as Githeri—a local dish made from maize and beans.

Farmers of the village of Kathaka Kaome in Embu district near Mount Kenya are saying that quality protein maize (QPM) is as nutritious as Githeri—a local dish made from maize and beans.

A CIMMYT research team is using an old but effective technique to get a head start on some very advanced crop science. Their aim is to breed high yielding maize that also resists infection by a dangerous fungus. As part of a USAID-funded project, the team uses ultraviolet or black light to identify maize that inhibits Aspergillus flavus, a fungus that produces potent toxins known as aflatoxins.

A CIMMYT research team is using an old but effective technique to get a head start on some very advanced crop science. Their aim is to breed high yielding maize that also resists infection by a dangerous fungus. As part of a USAID-funded project, the team uses ultraviolet or black light to identify maize that inhibits Aspergillus flavus, a fungus that produces potent toxins known as aflatoxins. Farmers seal the corn earworm’s fate in Peru with an oily approach.

Farmers seal the corn earworm’s fate in Peru with an oily approach.

New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance.

New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance.