A Maize for Farmers on the Edge

May, 2005

CIMMYT-Peru maize, Marginal 28, outstrips expectations for farmers in Peru

CIMMYT-Peru maize, Marginal 28, outstrips expectations for farmers in Peru

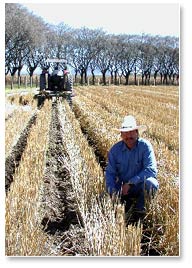

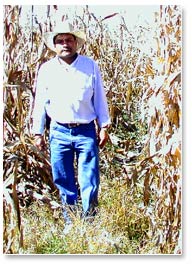

On a hillside that abuts more than 3,000 kilometers of Amazonian expanse beginning in Peru and reaching clear across Brazil to the Atlantic, farmer Virgilio Medina Bautista weeds his maize field under the stifling equatorial sun. He and his wife Sabina Bardales typically arise before dawn to cook a meal for their field workers, and will work all day until bedtime, around 9 p.m. “We come to the field with the food for brunch and ready to work,” Medina says. “It’s a hard life, but there’s no other way, for someone without an education.”

Like 90% of the farmers in this region of Peru—the lowland zones east of the Andes known as the “jungle”—as well as many on the coastal plains or in inter-Andean valleys, Medina sows Marginal 28. This open-pollinated maize variety, developed in the 1980s by Peru and CIMMYT, is popular for its high yields and broad adaptation. It provides two or three times the average yield of the local variety it replaced, and grows well in diverse environments. “Private companies have been trying to introduce maize hybrids here, but they yield only six tons per hectare,” says Edison Hidalgo, maize researcher from the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA) “El Porvenir” experiment station, whose staff help spread productive farming practices throughout the region. “Marginal 28 gives that or more, under similar management, and because it’s an open-pollinated variety, farmers don’t have to purchase new seed every season.”

Luis Narro, CIMMYT maize researcher in South America and a native of Peru who helped develop Marginal 28, says the cultivar’s adaptation and uses have far outstripped expectations. “This variety is sown most widely in jungle zones—truly marginal, lowland areas characterized by poor soils, heavy weeds, and frequent drought, to name a few constraints,” Narro says. “But I was just at a station in Ayacucho, at over 2,700 meters in the Andes, and saw seed production fields of Marginal 28 where the yields were probably going to hit seven tons per hectare.” Farmers in jungle areas use it chiefly in animal feeds or for export to the coast. Coastal farmers grow Marginal 28 because the seed is relatively cheap and yields high-quality forage for their dairy cattle. In the Andes, the grain goes for food and snacks.

Its adaptability may be explained in part by its genetically diverse pedigree, which even includes as a parent an internationally recognized variety from Thailand. “This suggests part of the value of a global organization like CIMMYT, which can combine contributions from around the world to develop a useful product for small-scale farmers,” Narro says.

Can Poor Farmers Stop Chopping Down Jungles?

Despite the clear benefits of Marginal 28, Peruvian farmers are still struggling as markets shift, production costs rise, and maize prices remain low. Farmer Jorge Dávila Dávila, of Fundo San Carlos, in Picota Province, in the Amazon region of Peru, grows maize, cotton, banana, and beans on his 10-hectare homestead. Because he is relatively far from the trans-Andean highways leading to the coast, where maize is in heavy demand for use in poultry feed, middlemen pay him only US $70 per ton of maize grain—well below world market prices. “Maize is a losing proposition; that’s why so many farmers here are in debt,” he says. “They can’t take their maize to local companies for a better price, because they already owe it to the middlemen who provide inputs.”

Despite the clear benefits of Marginal 28, Peruvian farmers are still struggling as markets shift, production costs rise, and maize prices remain low. Farmer Jorge Dávila Dávila, of Fundo San Carlos, in Picota Province, in the Amazon region of Peru, grows maize, cotton, banana, and beans on his 10-hectare homestead. Because he is relatively far from the trans-Andean highways leading to the coast, where maize is in heavy demand for use in poultry feed, middlemen pay him only US $70 per ton of maize grain—well below world market prices. “Maize is a losing proposition; that’s why so many farmers here are in debt,” he says. “They can’t take their maize to local companies for a better price, because they already owe it to the middlemen who provide inputs.”

Unlike most peers, Dávila makes ends meet through hard work and what he calls “an orderly approach” to farming. Many in the region slash and burn new brushland, cropping it for two or three seasons till fertility falls off, and then they move to new land. Dávila has stayed put for eight years on the same fields. “I tell my neighbors not to cut down their jungle,” he says. “I’ve seen that leaving it brings me rain.” With support from INIA researchers like Hidalgo, Dávila is testing conservation agriculture practices. For example, on one plot he plans to keep maize residues on the soil surface and seed the next crop directly into the soil without plowing. Research by CIMMYT and others has shown that this practice can cut production costs, trap and conserve moisture, and improve soil quality.

For further information, contact Luis Narro (l.narro@cgiar.org)

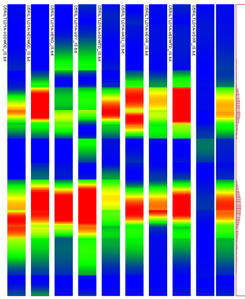

The HarvestPlus Maize group examines progress toward breeding maize with enhanced pro-vitamins A, iron, and zinc.

The HarvestPlus Maize group examines progress toward breeding maize with enhanced pro-vitamins A, iron, and zinc.

On the first day of the field visits, about 200 farmers from nearby villages greeted the delegation and expressed appreciation for new practices that were helping them to diversity agricultural production and conserve resources such as water and soil. The delegation was welcomed in Kapriwas, Gurgaon by senior officials of the

On the first day of the field visits, about 200 farmers from nearby villages greeted the delegation and expressed appreciation for new practices that were helping them to diversity agricultural production and conserve resources such as water and soil. The delegation was welcomed in Kapriwas, Gurgaon by senior officials of the  CIMMYT’s Board and staff are grateful to P.P. Manandhar, Nepal’s Secretary of Agriculture, and officials at the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives for their constant support for CIMMYT’s South Asia Regional Office, and to NARC Executive Director R.P. Sapkota and his colleagues for support and field visits. They are also most grateful to ICAR Director General Mangla Rai, Deputy Director of Crops and Horticulture G. Kalloo, and the many representatives of experiment stations, colleges, and universities in India who made the visit a success. The opportunity to meet and visit the field with representatives of DFID, FAO, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, SDC, USAID, and the World Bank, among others, was also greatly appreciated.

CIMMYT’s Board and staff are grateful to P.P. Manandhar, Nepal’s Secretary of Agriculture, and officials at the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives for their constant support for CIMMYT’s South Asia Regional Office, and to NARC Executive Director R.P. Sapkota and his colleagues for support and field visits. They are also most grateful to ICAR Director General Mangla Rai, Deputy Director of Crops and Horticulture G. Kalloo, and the many representatives of experiment stations, colleges, and universities in India who made the visit a success. The opportunity to meet and visit the field with representatives of DFID, FAO, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, SDC, USAID, and the World Bank, among others, was also greatly appreciated. In eastern and southern Africa, maize is the least expensive and most prevalent cereal crop, but quantity cannot make up for quality. A maize-dominated diet helps keep bellies full, but does not provide a balanced diet. Specifically, maize lacks the essential amino acids lysine and tryptophan necessary for efficient protein synthesis. Quality protein maize (QPM)—a type of maize with increased levels of those two crucial amino acids—is the focus of a recent CIMMYT co-authored publication based on two studies conducted in separate locations in Ethiopia1. The article delves into the role QPM can play in improving the nutritional status of young children in Ethiopia, where nearly 40% of children under five-years-old are underweight.

In eastern and southern Africa, maize is the least expensive and most prevalent cereal crop, but quantity cannot make up for quality. A maize-dominated diet helps keep bellies full, but does not provide a balanced diet. Specifically, maize lacks the essential amino acids lysine and tryptophan necessary for efficient protein synthesis. Quality protein maize (QPM)—a type of maize with increased levels of those two crucial amino acids—is the focus of a recent CIMMYT co-authored publication based on two studies conducted in separate locations in Ethiopia1. The article delves into the role QPM can play in improving the nutritional status of young children in Ethiopia, where nearly 40% of children under five-years-old are underweight. Infrared sensors help better target fertilizer for wheat on large commercial farms in northern Mexico, cutting production costs and reducing nitrogen run-off into coastal seas.

Infrared sensors help better target fertilizer for wheat on large commercial farms in northern Mexico, cutting production costs and reducing nitrogen run-off into coastal seas.

A new DNA detection service provided by CIMMYT and KARI responds to African researchers’ calls for modern technology.

A new DNA detection service provided by CIMMYT and KARI responds to African researchers’ calls for modern technology. A new genomic map that applies to a wide range of maize breeding populations should help scientists develop more drought tolerant maize.

A new genomic map that applies to a wide range of maize breeding populations should help scientists develop more drought tolerant maize.

Drought, arguably the greatest threat to food production worldwide, was the focal point of a high-level, weeklong workshop supported by the Rockefeller Foundation and CIMMYT, commencing May 24, in Cuernavaca, Mexico.

Drought, arguably the greatest threat to food production worldwide, was the focal point of a high-level, weeklong workshop supported by the Rockefeller Foundation and CIMMYT, commencing May 24, in Cuernavaca, Mexico.

How could a wheat research station in the middle of a maize-growing state become a resource for its neighbors? Campaigning for conservation agriculture and maize hybrids, CIMMYT’s Toluca Station superintendent Fernando Delgado Ramos is changing the way some farmers think about the plow. What started out as a crop rotation for a wheat experiment is now turning heads for its advances in maize yields.

How could a wheat research station in the middle of a maize-growing state become a resource for its neighbors? Campaigning for conservation agriculture and maize hybrids, CIMMYT’s Toluca Station superintendent Fernando Delgado Ramos is changing the way some farmers think about the plow. What started out as a crop rotation for a wheat experiment is now turning heads for its advances in maize yields.

Through their own determination, and with support from local researchers, CIMMYT, ICRISAT, and organizations in Australia, sub-Saharan African farmers are applying improved maize-legume cropping systems to grow more food and make money.

Through their own determination, and with support from local researchers, CIMMYT, ICRISAT, and organizations in Australia, sub-Saharan African farmers are applying improved maize-legume cropping systems to grow more food and make money. Faizal Ahmad and his brother Hayatt Mohammad are sharecroppers on this 8 hectare parcel of land. They pay the landowner a share and the crew that is harvesting gets a share, and with what is left, they try to feed their families, maybe sell a little.

Faizal Ahmad and his brother Hayatt Mohammad are sharecroppers on this 8 hectare parcel of land. They pay the landowner a share and the crew that is harvesting gets a share, and with what is left, they try to feed their families, maybe sell a little. At least three more varieties developed from materials originally from CIMMYT (some via the winter wheat breeding program in Turkey) are in the new varietal release pipeline that Afghanistan has implemented. They have already demonstrated in farmers’ fields that they are well-suited to local conditions and can provide more wheat per hectare than farmers currently harvest with yields in on-farm trials of almost 5 tons per hectare, double what most farmers get. These wheats can be seen in trials at the Dehdadi Research Farm near Mazur, almost within sight of the sharecropping brothers.

At least three more varieties developed from materials originally from CIMMYT (some via the winter wheat breeding program in Turkey) are in the new varietal release pipeline that Afghanistan has implemented. They have already demonstrated in farmers’ fields that they are well-suited to local conditions and can provide more wheat per hectare than farmers currently harvest with yields in on-farm trials of almost 5 tons per hectare, double what most farmers get. These wheats can be seen in trials at the Dehdadi Research Farm near Mazur, almost within sight of the sharecropping brothers.