When a devastating stripe rust epidemic hit Ethiopia last year, newly-released wheat varieties derived from international partnerships proved resistant to the disease, and are now being multiplied for seed.

Wheat farmers and breeders are embroiled in a constant arms race against the rust diseases, as new rust races evolve to conquer previously resistant varieties. Ethiopia’s wheat crop became the latest casualty when a severe stripe rust epidemic struck in 2010. “The dominant wheat varieties were hit by this disease, and in some of the cases where fungicide application was not done there was extremely high yield loss,” says Firdissa Eticha, national wheat research program coordinator with the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). “This is a threat for the future because there is climate change—which has already been experienced in Ethiopia—and the varieties which we have at hand were totally hit by this stripe rust.”

Ethiopia is not alone; stripe rust has become a serious problem across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, with epidemics in 2009 and 2010 which many countries have struggled to control. What’s new is the evolution of stripe rust races that are able to overcome Yr27, a major rust resistance gene that many important wheat varieties rely on. Although recent weather conditions have allowed the new rust races to thrive, they first began to emerge more than a decade ago, and CIMMYT’s wheat program, always looking forward to the next threat, began selection for resistance to Yr27-virulent races in 1998.

“CIMMYT has a number of wheat lines that have shown good-to-excellent resistance to stripe rust without relying on Yr27, in screening in Mexico, Ecuador, and Kenya,” says Ravi Singh, CIMMYT distinguished scientist and rust expert who leads the breeding effort in Mexico. Many of these are also resistant to the stem rust race Ug99 and have 10-15% higher yields than currently-grown varieties, according to Singh. The current step is to work with national programs to identify and promote the most useful of the resistant materials for their environments—a process that was underway in Ethiopia when the epidemic struck.

Eticha is leading his country’s fight against stripe rust. Reflecting on the disease, he says: “For me it is as important as stem rust. I find it like a wildfire when there is a susceptible variety. You see very beautiful fields actually, yellow like a canola field in flower. But for farmers it is a very sad sight. Stripe rust can cause up to 100% yield loss.” There is no official figure yet on the overall loss to Ethiopia’s wheat harvest for 2010, but it is expected to be more than 20%.

Stripe rust symptoms in the field in Ethiopia. | Photo: Firdissa Eticha

The other common name for stripe rust is yellow rust. Severely-infected plants look bright yellow, due to a photosynthesis-blocking coating of spores of the fungus Puccinia striiformis, which causes the disease. These spores are yellow to orange-yellow in color, and form pustules. These usually appear as narrow stripes along the leaves, and can cover the leaves in susceptible varieties, as well as affecting the leaf sheaths and the spikes. The disease lowers both yield and grain quality, causing stunted and weakened plants, fewer spikes, fewer grains per spike, and shriveled grains with reduced weight.

Epidemic flourishes with damp weather

Normally, Ethiopia has two distinct rainy seasons, one short and one main, allowing for two wheat cropping cycles per year. However, 2010 saw persistent gentle rains throughout the year, with prolonged dews and cool temperatures—perfect weather for stripe rust. Most wheat varieties planted in Ethiopia were susceptible, including the two most popular, Kubsa and Galema, so damage was severe. Under normal conditions, the disease only attacks high-altitude wheat in Ethiopia, but last year it was rampant even at low altitudes. This could reflect the appearance of a new race that is less temperature sensitive, or simply the unusual weather conditions; Ethiopian researchers are currently waiting for the results of a rust race analysis.

There was little Ethiopia could do to prevent the epidemic; imported fungicides controlled the disease where they were applied on time, but supplies were limited and expensive. Newly-released, resistant varieties provide a way out of danger. In particular, two CIMMYT lines released in Ethiopia in 2010 proved resistant to stripe rust in their target environments: Picaflor#1, which was released in Ethiopia as Kakaba, and Danphe#1, released as Danda’a. Picaflor#1 is targeted to environments where Kubsa is grown, and so has the potential to replace it, and Danphe#1 could similarly replace Galema. Both varieties are also high-yielding and resistant to Ug99.

CIMMYT scientists Hans-Joachim Braun (left) and Bekele Abeyo visit the fields of the Kulumsa Research Station where CIMMYT materials resistant to stripe rust are being multiplied for seed supply to Ethiopian farmers.

Seed multiplication of resistant CIMMYT varieties

As soon as the situation became clear, EIAR and the Ethiopian Seed Enterprise (the state-owned organization responsible for multiplication and distribution of improved seed of all major crops in Ethiopia) worked together to speed the multiplication of seed of these varieties, using irrigation during the dry seasons. This is happening now, with almost 500 hectares under multiplication over the winter—421 of Picaflor#1 and 70 of Danphe#1. Financial support from this project came from the USAID Famine Fund. Two resistant lines from the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) were released in Ethiopia in 2011, and will add to the diversity for resistance.

Eticha does not foresee any difficulty encouraging farmers to adopt the new varieties. In 2010 they were grown by 900 farmers on small on-farm demonstration plots, as part of EIAR’s routine annual program, so they have been seen—free of stripe rust—by thousands of farmers, and there will be more demonstration plots as more seed becomes available. However, “farmers are at risk still even if the varieties are there,” he says, “the problem is seed supply.” Some seed will reach farmers this year, but the priority will be ongoing multiplication to build up availability as fast as possible.

Hans-Joachim Braun, director of CIMMYT’s Global Wheat Program, visited Ethiopia in 2010. “The epidemic was a real wake-up call,” he says. “Researchers have known for more than ten years that the varieties grown are susceptible. Farmers are not aware of the danger, so it is the responsibility of researchers and seed producers, if we know a variety is susceptible, to replace it with something better.”

|

Exploring rust solutions in Syria

The ongoing fight against the wheat rust diseases is an international, collaborative effort involving many partners in national programs and international organizations. CIMMYT works closely with ICARDA, which leads efforts against the wheat rust diseases in Central and West Asia and North Africa. At the International Wheat Stripe Rust Symposium, organized by ICARDA in Aleppo, Syria, during 18-20 April 2011, global experts developed strategies to prevent future rust outbreaks and to ensure the control and reduction of rust diseases in the long term.

Other participating organizations included CIMMYT, the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative (BGRI), the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the UN, the International Development Research Center (IDRC, Canada), and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). More than 100 scientists from 31 countries presented work and shared ideas on wheat rust surveillance and monitoring, development and promotion of rust-resistant wheat varieties, and crop diversity strategies to slow the progress of rust outbreaks.

CIMMYT was represented by Hans-Joachim Braun and Ravi Singh. “Wheat crops and stripe rust like exactly the same conditions,” says Braun, “and they both love nitrogen. This means that where a farmer has a high yield potential, stripe rust takes it away, if the wheat variety is susceptible. In addition to the really devastating epidemics, the disease is very important because even in bumper years, farmers who grow susceptible varieties still can’t get a good yield.”

One thing all the attendees agreed on was the immediacy of the rust threat. New variants of both stem rust (also known as black rust) and stripe rust (or yellow rust), able to overcome the resistance of popular wheat varieties, are thriving under the more variable conditions caused by climate change, increasing their chances of spreading rapidly. Breeders in turn are quickly developing the varieties farmers need, with durable resistance to stem and stripe rust, as well as improved yield performance, drought tolerance, and regional suitability.

Other major areas of focus are the development of systems for monitoring and surveillance of rust to enable rapid response to initial outbreaks, and overcoming bottlenecks in getting resistant seed quickly to farmers. There is much to be done, but Singh is confident: “If donors, including national programs and the private sector, are willing to invest in wheat research and seed production, we can achieve significant results in a short time.”

|

|

“Ethiopian scientists responded quickly to the epidemic”, says Braun, “but there were heavy losses in 2010. What we need is better communications between scientists, seed producers, and decision makers to ensure the quick replacement of varieties.”

Building on a strong partnership

The value of the collaboration between CIMMYT and Ethiopia is already immeasurable for both partners. CIMMYT materials are routinely screened for rust at Meraro station, an Ethiopian hotspot, in increasing numbers as rust diseases have returned to the spotlight in recent years. CIMMYT lines are also a crucial input for Ethiopia’s national program.

“The contribution of CIMMYT is immense for us,” says Eticha. “CIMMYT provides us with a wide range of germplasm that is almost finished technology—one can say ready materials, that can be evaluated and released as varieties that can be used by farming communities.” Ethiopia has favorable agro-environments for wheat production, and the bread wheat area is expanding because of its high yields compared to indigenous tetraploid wheats. “Wheat is the third most important cereal crop in Ethiopia,” explains Eticha, “and it is really very important in transforming Ethiopia’s economy.”

Bekele Abeyo, CIMMYT senior scientist and wheat breeder based in Ethiopia, works closely with the national program. CIMMYT helps in many ways, he explains, for example with training and capacity building, as well as donation of materials, including computers, vehicles, and even chemicals for research. “In addition, we assign scientists to work closely with the national program, and facilitate germplasm exchange, providing high-yielding, disease resistant, widely-adapted varieties.” Speaking of the stripe rust epidemic, he says, “last year, the Ethiopian government spent more than USD 3.2 million just to buy fungicides, so imagine, the use of resistant varieties can save a lot of money. Most farmers are not able to buy these expensive fungicides. During the epidemic, fungicides were selling for three to four times their normal price, so you can see the value of resistant varieties.”

“I think East Africa is colonized by rust. Unless national programs work hard to overcome and contain disease pressure, wheat production is under great threat,” says Abeyo. “It is very important that we continue to strengthen the national programs to overcome the rust problem in the region.” With Yr27-virulent stripe rust races now widespread throughout the world, Ethiopia’s story has echoes in many CIMMYT partner countries. The challenge is to work quickly together to identify and replace susceptible varieties with the new, productive, resistant materials.

For more information: Bekele Abeyo, senior scientist and wheat breeder (b.abeyo@cgiar.org)

New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance.

New, elite maize lines from CIMMYT offer enhanced nutrition and disease resistance.

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

CIMMYT-led international efforts to identify and deploy sources of resistance to the virulent Ug99 strain of stem rust have received coverage on ABC1, the primary television channel of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. As the price of wheat goes up, countries such as the Republic of Mauritius are feeling the pinch. A former British colony off the coast of Madagascar, it imports most of its wheat from France and Australia. But with help from CIMMYT, the island has started trials to grow its own wheat—and results to date look promising.

As the price of wheat goes up, countries such as the Republic of Mauritius are feeling the pinch. A former British colony off the coast of Madagascar, it imports most of its wheat from France and Australia. But with help from CIMMYT, the island has started trials to grow its own wheat—and results to date look promising.

Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums.

Three high-quality wheat varieties developed by researchers from the Shandong Academy of Agricultural Science and the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (CAAS), drawing on CIMMYT wheat lines and technical support, were sown on more than 8 million hectares during 2002-2006, according to a recent CAAS economic study. They contributed an additional 2.4 million tons of grain—worth USD 513 million, with quality premiums. Borlaug, still a consultant with CIMMYT, is also the President of the Sasakawa Africa Association, which is devoted to improving the lives of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa. One of his reasons for visiting Obregón this time was to see and learn about a technology developed by Oklahoma State University (OSU) and CIMMYT. The approach allows farmers easily and cheaply to determine the optimum application of fertilizer for a developing wheat or maize crop. Fertilizer resources are scarce in much of Africa, so timely application of the correct amounts can save farmers money and help produce a better crop.

Borlaug, still a consultant with CIMMYT, is also the President of the Sasakawa Africa Association, which is devoted to improving the lives of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa. One of his reasons for visiting Obregón this time was to see and learn about a technology developed by Oklahoma State University (OSU) and CIMMYT. The approach allows farmers easily and cheaply to determine the optimum application of fertilizer for a developing wheat or maize crop. Fertilizer resources are scarce in much of Africa, so timely application of the correct amounts can save farmers money and help produce a better crop.

A radio program in Nepal brings information to farmers in a language they understand.

A radio program in Nepal brings information to farmers in a language they understand.

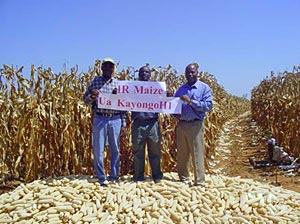

Experimental auctions in Kenya gauge farmer interest in vitamin A-enriched maize.

Experimental auctions in Kenya gauge farmer interest in vitamin A-enriched maize. Determining how consumers will balance their desire for nutritionally superior maize while sacrificing the color to which they are accustomed sheds light on whether or not biofortified maize will be readily adopted. “Despite a need for this knowledge, very few consumer studies of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa have been done,” says Hugo De Groote, CIMMYT economist.

Determining how consumers will balance their desire for nutritionally superior maize while sacrificing the color to which they are accustomed sheds light on whether or not biofortified maize will be readily adopted. “Despite a need for this knowledge, very few consumer studies of the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa have been done,” says Hugo De Groote, CIMMYT economist. In 2009, out of a global population of 6.8 billion people, more than 1 billion regularly woke up and went to bed hungry. By 2050 the population is expected to grow to 9.1 billion people, most of whom will be in developing countries. Unless we can increase global food production by 70%, the number of chronically hungry will continue to swell. To help ensure global food security, a new research consortium aims to boost yields of wheat—a major staple food crop.

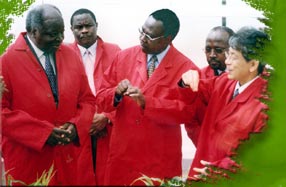

In 2009, out of a global population of 6.8 billion people, more than 1 billion regularly woke up and went to bed hungry. By 2050 the population is expected to grow to 9.1 billion people, most of whom will be in developing countries. Unless we can increase global food production by 70%, the number of chronically hungry will continue to swell. To help ensure global food security, a new research consortium aims to boost yields of wheat—a major staple food crop. The official opening on 23 June 2004 of a level-two biosafety greenhouse in Nairobi, Kenya was marked by happy fanfare, but more importantly, a serious commitment from the highest levels to use biotechnology to help solve Africa’s pressing agricultural problems.

The official opening on 23 June 2004 of a level-two biosafety greenhouse in Nairobi, Kenya was marked by happy fanfare, but more importantly, a serious commitment from the highest levels to use biotechnology to help solve Africa’s pressing agricultural problems. The President of Kenya, his Excellency the Hon. Mwai Kibaki, officially launched the facility. He was joined by Masa Iwanaga, CIMMYT’s Director General; Romano Kiome, Director of KARI; Andrew Bennett, Executive Director of the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, which provided funds for the new facility; Shivaji Pandey, Director of CIMMYT’s African Livelihoods Program (ALP); and the Hon. Kipruto Arap Kirwa, Minister of Agriculture.

The President of Kenya, his Excellency the Hon. Mwai Kibaki, officially launched the facility. He was joined by Masa Iwanaga, CIMMYT’s Director General; Romano Kiome, Director of KARI; Andrew Bennett, Executive Director of the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, which provided funds for the new facility; Shivaji Pandey, Director of CIMMYT’s African Livelihoods Program (ALP); and the Hon. Kipruto Arap Kirwa, Minister of Agriculture.

Looks can deceive. Striga, a deadly parasitic plant, produces a lovely flower but sucks the life and yields out of crops across Africa and Asia. A new strain of improved maize seed is helping farmers reclaim their invaded crop lands.

Looks can deceive. Striga, a deadly parasitic plant, produces a lovely flower but sucks the life and yields out of crops across Africa and Asia. A new strain of improved maize seed is helping farmers reclaim their invaded crop lands.

Two years after its release by Western Seed Company, WH502, a hybrid maize variety derived from research by CIMMYT and partners in eastern Africa, was being grown by nearly a fifth of the farmers surveyed in western Kenya for its high yields, resistance to lodging, tolerance to low nitrogen soils, and other good qualities.

Two years after its release by Western Seed Company, WH502, a hybrid maize variety derived from research by CIMMYT and partners in eastern Africa, was being grown by nearly a fifth of the farmers surveyed in western Kenya for its high yields, resistance to lodging, tolerance to low nitrogen soils, and other good qualities.