The doubled haploid (DH) technology enables rapid development of completely homozygous maize lines and offers significant opportunities for fast-track development and release of elite cultivars. Besides simplified logistics and reduced costs, use of DH lines in conjunction with molecular markers significantly improves genetic gains and breeding efficiency. DH lines also are valuable tools in marker-trait association studies, molecular marker-assisted or genomic selection-based breeding, and functional genomics.

The doubled haploid (DH) technology enables rapid development of completely homozygous maize lines and offers significant opportunities for fast-track development and release of elite cultivars. Besides simplified logistics and reduced costs, use of DH lines in conjunction with molecular markers significantly improves genetic gains and breeding efficiency. DH lines also are valuable tools in marker-trait association studies, molecular marker-assisted or genomic selection-based breeding, and functional genomics.

Generating DH lines involves four major steps: (1) In vivohaploid induction; (2) haploid seed identification using morphological markers; (3) chromosome doubling of putative haploids; and (4) generating D1 (DH) seed from D0 seedlings. In vivo haploid induction is achieved by crossing a specially developed maize genetic stock called an “inducer” (as male) with a source population (as female) from which homozygous DH lines are developed.

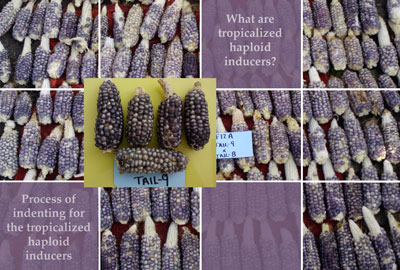

What are tropicalized haploid inducers?

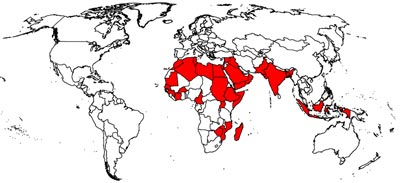

Adoption of DH technology by public maize breeding programs and small- and mediumscale enterprise (SME) seed companies, especially in developing countries, is limited by the lack of inducers adapted to the tropical/subtropical conditions. The CIMMYT Global Maize Program, in collaboration with the Institute of Plant Breeding, Seed Science and Population Genetics of the University of Hohenheim (UHo) now has tropical haploid inducers for sharing with the interested institutions under the terms outlined below.

The tropically adapted inducer lines (TAILs) developed by CIMMYT and UHo showed high haploid induction capacity (~8-10%) and better agronomic performance than temperate inducers, in trials at two CIMMYT experiment stations in Mexico. A haploid inducer hybrid developed using these TAILs revealed heterosis for plant vigor and pollen production under tropical conditions, while maintaining similar haploid induction rates (~8-10%). CIMMYT and UHo decided to share the seed and grant authorization for use of one of the tropicalized haploid inducer lines (one of the parents of a hybrid inducer) and the hybrid inducer to interested applicants, after signing of the relevant material transfer agreement (MTA) and with restrictions to protect the intellectual property rights of both institutions for the inducer lines.

Process of indenting for the tropicalized haploid inducers

Interested applicants should send a letter of intent or an expression of interest in the tropicalized haploid inducers. CIMMYT may seek more information, if required, and will share the relevant MTA template for signing by applicants. The general guidelines to obtain inducers for research use and commercial use are as follows.

For research use by publicly-funded national agricultural research systems

Publicly-funded institutions interested in access to the haploid inducers for specific purposes (e.g., to develop DH lines for breeding programs) may send a letter of intent or expression of interest to CIMMYT. For eligible institutions, the haploid inducers will be provided free-of-charge by CIMMYT and UHo, after signing of a Research Use MTA. Commercial use of the inducers by institutions or others should be in accordance with a separate license agreement for commercial use (as given below).

For commercial use

Applicants may access the inducers for commercial use pursuant to signing of a Material Transfer and License Agreement with CIMMYT and UHo. Applicants shall pay UHo a one-time licence fee of USD 25,000 for provision of seed of two haploid inducers; these include one of the parents of a tropicalized haploid inducer hybrid and the haploid inducer hybrid itself. If applicants wish to access the other parent of the haploid inducer hybrid, an additional one-time licence fee of $10,000 will be payable to UHo.

Acknowledgments

Generous support for joint research on doubled haploids by CIMMYT and the University of Hohenheim has come from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Howard G. Buffett Foundation; SAGARPA, the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food.; USAID (US Agency for International Development); Dr. Dr. h. c. Herrmann Eiselen and the Foundation fiat panis, Ulm, Germany; the Tiberius Services AG, Stuttgart, Germany; Vilmorin Seed Company; DTMA (Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa) project.;MAIZE CGIAR Research Program; and the International Maize Improvement Consortium (IMIC) project under MasAgro (Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture).

For further details, please contact:

Dr. BM Prasanna, Director, Global Maize Program, CIMMYT ( b.m.prasanna@cgiar.org), or

Dr. Vijay Chaikam, DH Specialist, Global Maize Program, CIMMYT ( v.chaikam@cgiar.org)

Maize Doubled Haploid Facility for Africa (3.17 MB)

The doubled haploid (DH) technology enables rapid development of completely homozygous maize lines and offers significant opportunities for fast-track development and release of elite cultivars. Besides simplified logistics and reduced costs, use of DH lines in conjunction with molecular markers significantly improves genetic gains and breeding efficiency. DH lines also are valuable tools in marker-trait association studies, molecular marker-assisted or genomic selection-based breeding, and functional genomics.

Generating DH lines involves four major steps: (1) In vivohaploid induction; (2) haploid seed identification using morphological markers; (3) chromosome doubling of putative haploids; and (4) generating D1 (DH) seed from D0 seedlings. In vivo haploid induction is achieved by crossing a specially developed maize genetic stock called an “inducer” (as male) with a source population (as female) from which homozygous DH lines are developed.

What are tropicalized haploid inducers?

Adoption of DH technology by public maize breeding programs and small- and mediumscale enterprise (SME) seed companies, especially in developing countries, is limited by the lack of inducers adapted to the tropical/subtropical conditions. The CIMMYT Global Maize Program, in collaboration with the Institute of Plant Breeding, Seed Science and Population Genetics of the University of Hohenheim (UHo) now has tropical haploid inducers for sharing with the interested institutions under the terms outlined below.

The tropically adapted inducer lines (TAILs) developed by CIMMYT and UHo showed high haploid induction capacity (~8-10%) and better agronomic performance than temperate inducers, in trials at two CIMMYT experiment stations in Mexico. A haploid inducer hybrid developed using these TAILs revealed heterosis for plant vigor and pollen production under tropical conditions, while maintaining similar haploid induction rates (~8-10%). CIMMYT and UHo decided to share the seed and grant authorization for use of one of the tropicalized haploid inducer lines (one of the parents of a hybrid inducer) and the hybrid inducer to interested applicants, after signing of the relevant material transfer agreement (MTA) and with restrictions to protect the intellectual property rights of both institutions for the inducer lines.

Process of indenting for the tropicalized haploid inducers

Interested applicants should send a letter of intent or an expression of interest in the tropicalized haploid inducers. CIMMYT may seek more information, if required, and will share the relevant MTA template for signing by applicants. The general guidelines to obtain inducers for research use and commercial use are as follows.

For research use by publicly-funded national agricultural research systems

Publicly-funded institutions interested in access to the haploid inducers for specific purposes (e.g., to develop DH lines for breeding programs) may send a letter of intent or expression of interest to CIMMYT. For eligible institutions, the haploid inducers will be provided free-of-charge by CIMMYT and UHo, after signing of a Research Use MTA. Commercial use of the inducers by institutions or others should be in accordance with a separate license agreement for commercial use (as given below).

For commercial use

Applicants may access the inducers for commercial use pursuant to signing of a Material Transfer and License Agreement with CIMMYT and UHo. Applicants shall pay UHo a one-time licence fee of USD 25,000 for provision of seed of two haploid inducers; these include one of the parents of a tropicalized haploid inducer hybrid and the haploid inducer hybrid itself. If applicants wish to access the other parent of the haploid inducer hybrid, an additional one-time licence fee of $10,000 will be payable to UHo.

Acknowledgments

Generous support for joint research on doubled haploids by CIMMYT and the University of Hohenheim has come from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Howard G. Buffett Foundation; SAGARPA, the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food.; USAID (US Agency for International Development); Dr. Dr. h. c. Herrmann Eiselen and the Foundation fiat panis, Ulm, Germany; the Tiberius Services AG, Stuttgart, Germany; Vilmorin Seed Company; DTMA (Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa) project.;MAIZE CGIAR Research Program; and the International Maize Improvement Consortium (IMIC) project under MasAgro (Sustainable Modernization of Traditional Agriculture).

For further details, please contact:

Dr. BM Prasanna, Director, Global Maize Program, CIMMYT ( b.m.prasanna@cgiar.org), or

Dr. Vijay Chaikam, DH Specialist, Global Maize Program, CIMMYT ( v.chaikam@cgiar.org)

On 03 January 2013, 63-year-old Ghanaian-born maize breeder Strafford Twumasi-Afriyie succumbed to cancer, leaving a substantive legacy that includes the creation of the world’s most widely-sown quality protein maize (QPM) variety,

On 03 January 2013, 63-year-old Ghanaian-born maize breeder Strafford Twumasi-Afriyie succumbed to cancer, leaving a substantive legacy that includes the creation of the world’s most widely-sown quality protein maize (QPM) variety,  The doubled haploid (DH) technology enables rapid development of completely homozygous maize lines and offers significant opportunities for fast-track development and release of elite cultivars. Besides simplified logistics and reduced costs, use of DH lines in conjunction with molecular markers significantly improves genetic gains and breeding efficiency. DH lines also are valuable tools in marker-trait association studies, molecular marker-assisted or genomic selection-based breeding, and functional genomics.

The doubled haploid (DH) technology enables rapid development of completely homozygous maize lines and offers significant opportunities for fast-track development and release of elite cultivars. Besides simplified logistics and reduced costs, use of DH lines in conjunction with molecular markers significantly improves genetic gains and breeding efficiency. DH lines also are valuable tools in marker-trait association studies, molecular marker-assisted or genomic selection-based breeding, and functional genomics.

It was another exhausting, but productive day at the Wheat for Food Security in Africa conference at Addis Ababa, culminating in a wonderful evening of traditional dancing and the Injera cuisine so typical of Ethiopia. In case you missed any of our live tweeting during the day (#W4A), here is a brief roundup of the main events. It would be impossible to describe everything that happened in one short post, but this was a day likely to produce impacts in the months to come.

It was another exhausting, but productive day at the Wheat for Food Security in Africa conference at Addis Ababa, culminating in a wonderful evening of traditional dancing and the Injera cuisine so typical of Ethiopia. In case you missed any of our live tweeting during the day (#W4A), here is a brief roundup of the main events. It would be impossible to describe everything that happened in one short post, but this was a day likely to produce impacts in the months to come.

After two days in

After two days in  An exhausting, productive day on Day Two of Wheat for Food Security in Africa. Participants arrived bright and early for expert presentations and round-table discussions on abiotic/biotic stresses, market and seed systems, wheat systems and quality, and country outlooks.

An exhausting, productive day on Day Two of Wheat for Food Security in Africa. Participants arrived bright and early for expert presentations and round-table discussions on abiotic/biotic stresses, market and seed systems, wheat systems and quality, and country outlooks.