Mother-baby trials promote conservation agriculture in Manica, Mozambique

A testament to increased climate variability and risk for farming systems already operating on the razor’s edge, the 2014-15 cropping season will be recognized as a sad write-off by most farmers in Central Mozambique. The rains started six weeks late and most of the rainfall fell in only two months (normally it’s distributed over four), followed by a long drought and some few showers at the end.

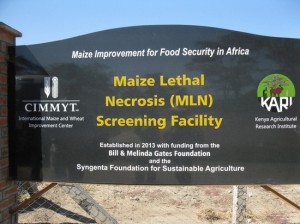

But with funds from the CGIAR Research Program on Maize, partners from the Instituto de Investigação Agrária de Moçambique (IIAM) and CIMMYT are working with farmers in Manica Province, Mozambique, to test and promote conservation agriculture practices that better capture and retain precious precipitation, among other advantages.

As part of this, they have revived “mother-baby” trials, a participatory methodology pioneered over a decade ago by CIMMYT for testing drought tolerant maize in Africa and which was subsequently adapted for diverse agronomic practices and is used by researchers worldwide.

Comprising field experiments grown in farming communities, mother-baby trials feature a centrally-located mother trial that is set up with researchers’ support. Baby trials, which contain subsets of the mother-trial treatments, are grown, managed and evaluated by interested farmers.

Moving from “business as usual” to innovation

In Machipanda, a small village in Manica on the border with Zimbabwe, IIAM maize breeder Dr. David Mariote established three mother trials, each with two conservation agriculture-based systems and a conventional control plot, combined with four maize varieties from the Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa (DTMA) project, which is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and a traditional variety, in full rotation with cowpeas.

Farmers then put up the baby trials from a menu of practices that included direct seeding with no tillage, crop rotations, residue retention, herbicide applications, fertilizer use and improved varieties. Interest was high: 54 farmers grew baby trials and some even extended their plots beyond the designated areas, in the excitement of trying something new, according to Mariote.

“Conditions are changing fast; business as usual is no longer an option,” Mariote said. “We have to offer improved technologies that farmers can use to mitigate negative effects from climate change and improve their lives.”

Mariote witnessed first-hand the synergistic benefits of combining conservation agriculture and drought tolerant maize, as part of work in the Platform on Agriculture Research and Technology Innovation (PARTI), a project funded through the US Agency for International Development (USAID) via Feed the Future and implemented by CIMMYT in Central and northern Mozambique.

With training from CIMMYT’s global maize program and technical backstopping from the CIMMYT global conservation agriculture program, Mariote sought new and stronger ways to spread these technologies. That’s when he hit upon mother-baby trials, which had never been used before with drought tolerant maize and conservation agriculture in tandem.

Farmers who grew baby trials unanimously agreed that new ways of farming are needed and that the trials had been eye-openers. In a community meeting, some said: “We often do not have money to buy expensive fertilizers but we have seen that with good agronomic practices and good maize varieties we can already increase our maize yields.”

More farmers in Machipanda have signed up for future baby trials and, as a clear indication of commitment and excitement about conservation agriculture and improved maize, they will use their own inputs to grow them.

In Malawi, the field visits began at Kasungu District, with 16 farmers and technical staff from Mozambique who were on an exchange visit also participating. The group visited outscaling initiatives by the National Association of Smallholder Farmers of Malawi (NASFAM), in which maize–groundnut rotations and maize–pigeonpea systems are being implemented through lead farmers. More than 120 households per field learning site are participating in the demonstrations on each of the five NASFAM sites visited.

In Malawi, the field visits began at Kasungu District, with 16 farmers and technical staff from Mozambique who were on an exchange visit also participating. The group visited outscaling initiatives by the National Association of Smallholder Farmers of Malawi (NASFAM), in which maize–groundnut rotations and maize–pigeonpea systems are being implemented through lead farmers. More than 120 households per field learning site are participating in the demonstrations on each of the five NASFAM sites visited.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – A social media crowd sourcing campaign initiated to celebrate the achievements of women has led to more than a dozen published blog story contributions about women in the maize and wheat sectors.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – A social media crowd sourcing campaign initiated to celebrate the achievements of women has led to more than a dozen published blog story contributions about women in the maize and wheat sectors.