Six investments to help family farmers thrive in the next decade

Family farmers produce more than 80% of the world’s food, but often have the least amount of access to support.

As the UN Decade of Family Farming launched on May 29, 2019, I talked with Trevor Nicholls, CEO of the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI), on this topic.

On an article published on the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Food Sustainability Index blog, we propose six key actions that can help family farmers thrive in the coming decade:

- Invest in women and youth: Make family farming work for all

- Attract young farmers into tech-smart farming

- Make climate-resilient crops more accessible

- Share practical plant health advice with family farmers

- Help family farmers diversify and grow more from less land

- Translate national and global goals into practical farming support

Read the full article

System uses plants to lure fall armyworm away from maize fields

Climate conditions in Nepal are suitable for the establishment of fall armyworm, which could cause considerable crop loss if not managed properly. The fall armyworm is a destructive pest that has a voracious appetite for maize and other crops. Through the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is working with the government of Nepal and other partners to address this imminent threat.

Chemical control of fall armyworm is too expensive and impractical for small-scale farmers, has negative human health effects, and can be a source of soil pollutants with a negative effect on biodiversity.

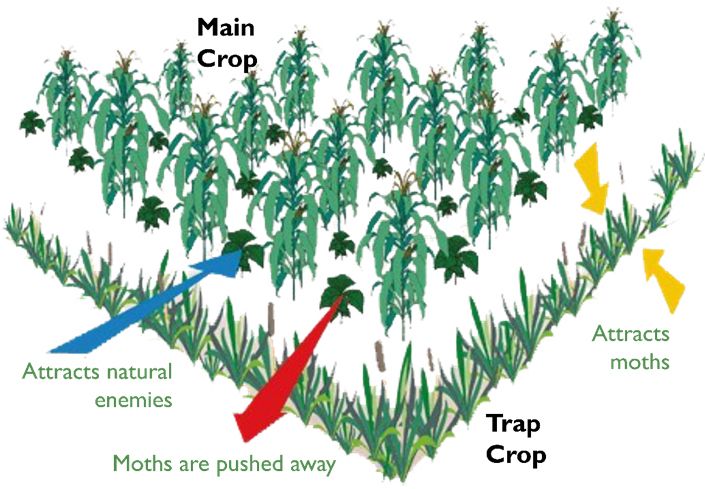

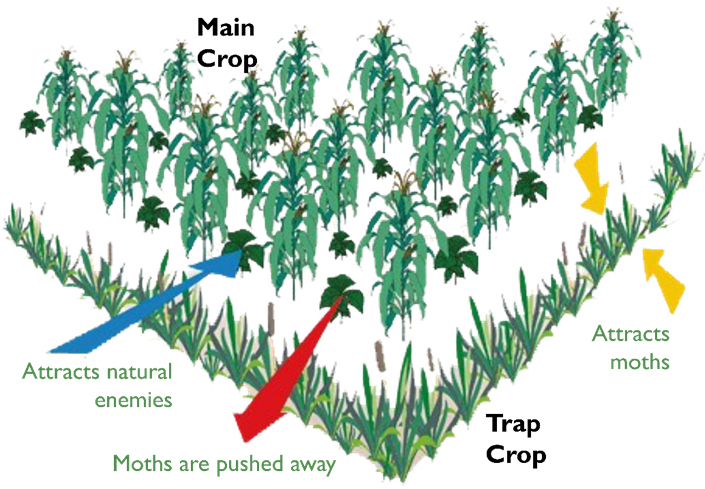

CIMMYT is currently evaluating the efficacy of push-pull cropping systems to control fall armyworm. Considered one of the most climate-smart technologies, push-pull systems use plant-pest ecology instead of harmful chemical insecticides to control weeds and insects. It is an environmentally friendly pest control method which is also economically viable for maize producers.

This system involves two types of crops: Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum) and silverleaf desmodium legume (Desmodium uncinatum).

Desmodium plants are intercropped with the rows of maize and Napier grass surrounds the maize crop. Desmodium produces volatile chemicals that repel fall armyworm moths, while the Napier grass produces chemicals that attract female moths. The resulting push-pull system takes the pest away from the maize field.

An additional benefit is that desmodium improves nitrogen fertility through biological nitrogen fixation, which may reduce nitrogen input in the long-term. Desmodium also provides ground cover for maize, controlling soil erosion and offering protection from extreme heat conditions. Both desmodium and Napier grass are excellent fodder crops for livestock.

Because of all these reasons, push-pull technology is highly beneficial to smallholders who are dependent on locally available inputs for their subsistence farming. It can also have a positive spiral effect on the environment.

Scientists in other regions are also looking at agro-ecological options to manage fall armyworm.

A burning issue

Pollution has become a part of our daily life: particulate matter in the air we breathe, organic pollutants and heavy metals in our food supply and drinking water. All of these pollutants affect the quality of human life and create enormous human costs.

India is home to 15 of the world’s cities with the highest air pollution, making it a matter of national concern. The country is the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emitter, where agriculture is responsible for 18% of total national emissions.

For decades, CIMMYT has engaged in the development and promotion of technologies to reduce our environmental footprint and conserve natural resources to help improve farmer’s productivity.

Efficient use of nitrogen fertilizers, better management of water, zero-tillage farming, and better residue management strategies offer viable solutions to beat air pollution originating from the agriculture sector. Mitigation measures have been developed, field tested, and widely adopted by farmers across Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan.

“Multi-lateral impacts of air pollution link directly it to various sustainability issues,” explained Balwinder Singh, Cropping Systems Simulation Modeler at CIMMYT. “The major sustainability issues regarding air quality revolve around the common question: How good is good enough to be sustainable? We need to decide how to balance the sustainable agriculture productivity and hazardous pollution levels. We need to have policies on the regulation of crop burning and in addition to policies surrounding methods to help reach appropriate air quality levels.”

Read the whole story

Sustainable tradition

The indigenous peoples who lived in central and southern Mexico thousands of years ago developed a resilient intercropping system to domesticate some of the basic grains and vegetables that contribute to a healthy diet.

Today, small farmers in roughly the same areas of Mexico continue to use this flexible system called “milpa” to grow chili, tomatoes, beans, squashes, seasonal fruits and maize, which are essential ingredients of most Mexican dishes.

An analysis of the Mexican diet done in the context of a recent report by the EAT – Lancet Commission found that Mexicans are eating too much animal fat but not enough fruits, vegetables, legumes and wholegrains. As a result, a serious public health issue is affecting Mexico due to the triple burden of malnutrition: obesity, micronutrient deficiency and/or low caloric intake. The study also urges Mexico to increase the availability of basic foodstuffs of higher nutritional value produced locally and sustainably.

Although changing food consumption habits may be hard to achieve, the traditional diet based on the milpa system is widely regarded as a healthy option in Mexico. Although nutritional diversity increases with the number of crops included in the milpa system, its nutritional impact in the consumers will also depend on their availability, number, uses, processing and consumption patterns.

Unfortunately, milpa farmers often practice slash-and-burn agriculture at the expense of soils and tropical rainforests. For that reason, it is also important to address some of the production-side obstacles on the way to a healthier diet, such as soil degradation and post-harvest losses, which have a negative effect on agricultural productivity and human health.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) engages in participatory field research and local capacity-building activities with farmers, local partners and authorities to foster innovation and to co-create strategies and procedures that help farmers produce food sustainably.

These efforts led Francisco Canul Poot, a milpa farmer from the Yucatan Peninsula, to adopt conservation agriculture concepts in his milpa and to stop burning soil residues since 2016. As a result, his maize yield grew by 70%, from 430 to 730 kg per hectare, and his income increased by $300 dollars. 15 farmers sharing property rights over communal land have followed his example since.

These outstanding results are encouraging more farmers to adopt sustainable intensification practices across Mexico, an important change considering that falling levels of nitrogen and phosphorus content in Mexican soils may lead to a 70 percent increase in fertilizer use by 2050.

By implementing a sustainable intensification project called MasAgro, CIMMYT contributes, in turn, to expand the use of sustainable milpa practices in more intensive production systems. CIMMYT is also using this approach in the Milpa Sustentable Península de Yucatán project.

At present, more than 500 thousand farmers have adopted sustainable intensification practices — including crop diversification and low tillage — to grow maize, wheat and related crops on more than 1.2 million hectares across Mexico.

Slow-release nitrogen fertilizers measure up

Maize, rice and wheat are the major staple crops in Nepal, but they are produced using a lot of fertilizer, which may become an environmental hazard if not completely used up in production. Unfortunately, most farmers apply fertilizers in an unbalanced way.

Urea is a common fertilizer used as a nitrogen source by Nepali farmers. If the time of application is not synchronized with crop uptake, the chances of losses through volatilization releasing ammonia and leaching are high, thereby creating environmental hazards in the atmosphere and downstream.

Through the Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is testing the application of environmentally friendly slow-release nitrogen fertilizer in maize production.

In particular, CIMMYT researchers examined the nutrient-use efficiency of briquetted urea and polymer-coated urea, also known as PCU.

Using regular urea, the efficiency of nitrogen use in maize is limited to 17 kg of grain per kg of nitrogen. Using briquetted urea and polymer-coated urea, efficiency increased to 24 and 28 kg of grain per kg of nitrogen respectively. A higher efficiency also suggests a reduction in losses to the environment.

Overall, results show that briquetted urea and polymer-coated urea can allow reduced nitrogen inputs by as much as 30-40% while maintaining the same yield levels achieved using current government fertilizer recommendations.

Similar to the maize trials, the application of slow-release nitrogen at a lower amount than the recommended rate in wheat showed similar agronomic results to the application of traditional urea at higher rates. Reduced losses allowed 40-50% less nitrogen fertilizer application but maintained the same yield levels as the current recommendation.

Although the cost of polymer-coated urea is comparatively expensive in the market unless subsidized, farmers applying briquetted urea save money and labor and can obtain 54% more profits.

“Briquetted urea is easy to use compared with traditional urea application, since its one-time application method saves labor. Moreover the yield performance is better,” said Devi Sara Thapa, a farmer from Surkhet district.

Climate change is affecting the yield of crops due to increased exposure to higher temperature, water stress and delayed or reduced monsoons, all impacting farmers’ incomes. The NSAF project promotes early maturing crop varieties that are resilient to such climatic stresses and can yield a positive harvest. The project works with seed companies and Nepal’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Development to deploy stress resilient maize and rice varieties packaged with cost efficient and effective soil fertility management practices in the project areas.

Researchers are testing and promoting early and extra early maturing open-pollinated varieties that have tolerance to drought or water stress conditions. These varieties are found to yield up to 7.5 tons per hectare and are ready for harvest in less than 100 days. This allows farmers, particularly in the hills and mid hills, to have another crop in the growing season. Such varieties will enhance farmers’ productivity and ensure food security at times of stressful environmental conditions.

CIMMYT is sharing the benefits of adopting these technologies to farmers, cooperatives and ago-dealers, through field demonstrations and farmer field days.

Project staff and partners use seeds and fertilizers that are approved by the Government of Nepal and the United States Agency for International Development’s environmental regulations on pesticide use or support. The team is promoting seed varieties appropriate for specific agroecological conditions and applying best practices on the use and application of fertilizers and integrated soil fertility management.

The Nepal Seed and Fertilizer (NSAF) project, implemented by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), aims to increase the availability of agriculture technologies to improve productivity in select value chains, including maize, rice, lentils, and high-value vegetables. Through the NSAF project, CIMMYT and its partners work to improve the capacity of the public and private sectors in their respective roles: to strengthen and develop commercial seed and fertilizer value chains and to develop markets systems to disseminate agricultural technologies throughout Nepal.

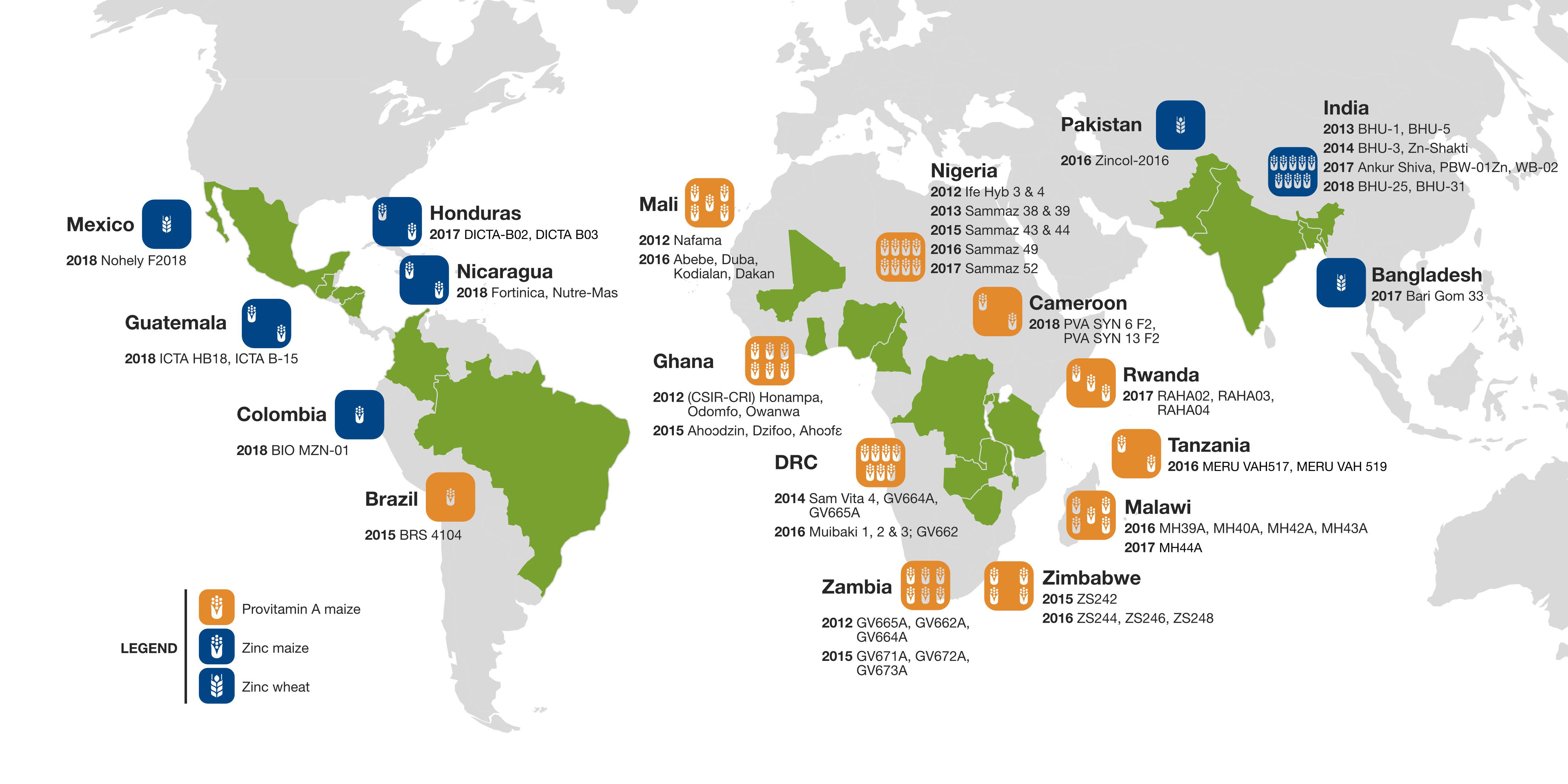

Biofortified maize and wheat can improve diets and health, new study shows

TEXCOCO, Mexico (CIMMYT) — More nutritious crop varieties developed and spread through a unique global science partnership are offering enhanced nutrition for hundreds of millions of people whose diets depend heavily on staple crops such as maize and wheat, according to a new study in the science journal Cereal Foods World.

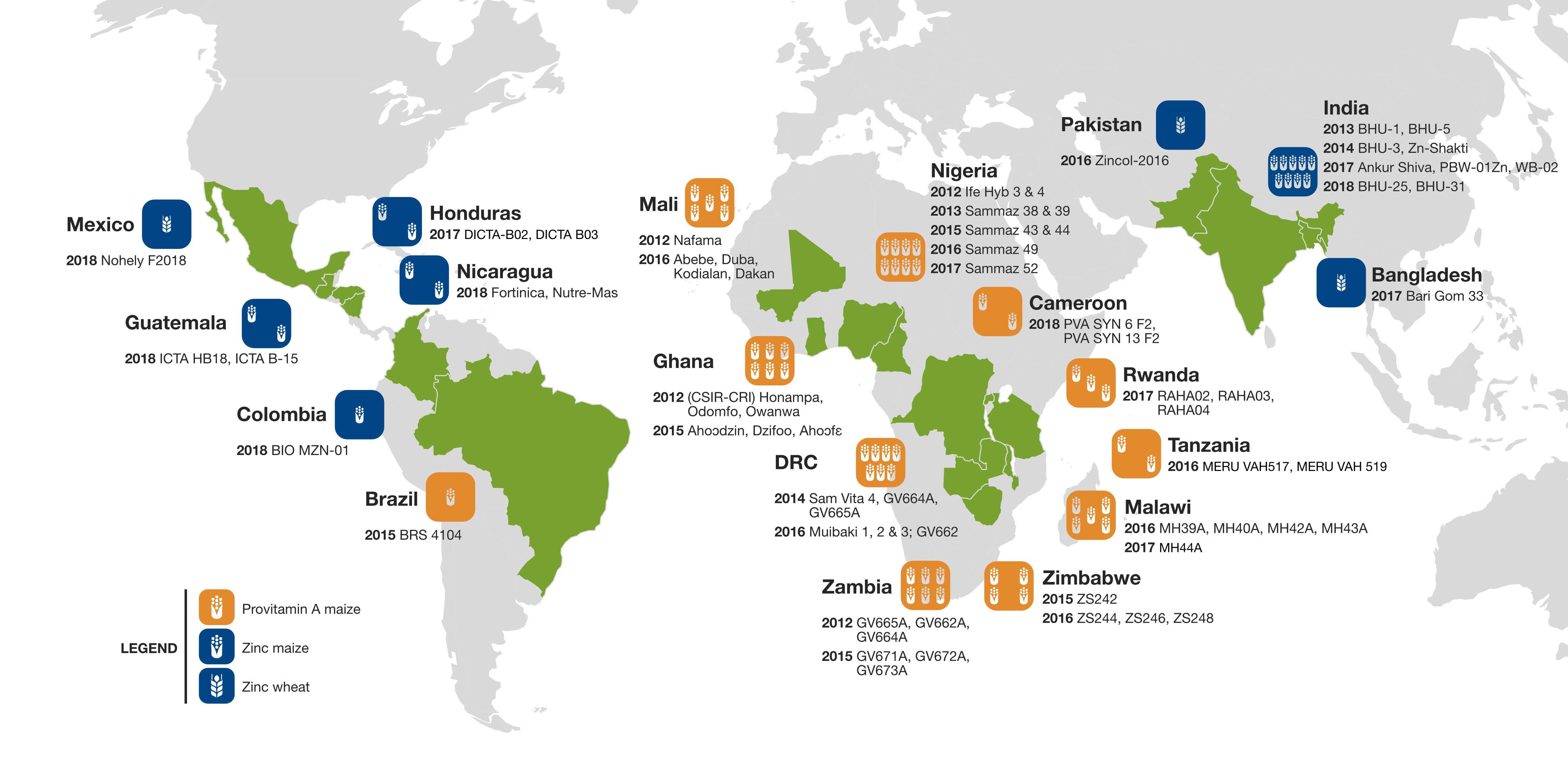

From work begun in the late 1990s and supported by numerous national research organizations and scaling partners, more than 60 maize and wheat varieties whose grain features enhanced levels of zinc or provitamin A have been released to farmers and consumers in 19 countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America over the last 7 years. All were developed using conventional cross-breeding.

“The varieties are spreading among smallholder farmers and households in areas where diets often lack these essential micronutrients, because people cannot afford diverse foods and depend heavily on dishes made from staple crops,” said Natalia Palacios, maize nutrition quality specialist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and co-author of the study.

More than 2 billion people worldwide suffer from “hidden hunger,” wherein they fail to obtain enough of such micronutrients from the foods they eat and suffer serious ailments including poor vision, vomiting, and diarrhea, especially in children, according to Wolfgang Pfeiffer, co-author of the study and head of research, development, delivery, and commercialization of biofortified crops at the CGIAR program known as “HarvestPlus.”

“Biofortification — the development of micronutrient-dense staple crops using traditional breeding and modern biotechnology — is a promising approach to improve nutrition, as part of an integrated, food systems strategy,” said Pfeiffer, noting that HarvestPlus, CIMMYT, and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) are catalyzing the creation and global spread of biofortified maize and wheat.

“Eating provitamin A maize has been shown to be as effective as taking Vitamin A supplements,” he explained, “and a 2018 study in India found that using zinc-biofortified wheat to prepare traditional foods can significantly improve children’s health.”

Six biofortified wheat varieties released in India and Pakistan feature grain with 6–12 parts per million more zinc than is found traditional wheat, as well as drought tolerance and resistance to locally important wheat diseases, said Velu Govindan, a breeder who leads CIMMYT’s work on biofortified wheat and co-authored the study.

“Through dozens of public–private partnerships and farmer participatory trials, we’re testing and promoting high-zinc wheat varieties in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Nepal, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe,” Govindan said. “CIMMYT is also seeking funding to make high-zinc grain a core trait in all its breeding lines.”

Pfeiffer said that partners in this effort are promoting the full integration of biofortified maize and wheat varieties into research, policy, and food value chains. “Communications and raising awareness about biofortified crops are key to our work.”

For more information or interviews, contact:

Mike Listman

Communications Consultant

International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT)

m.listman@cgiar.org, +52 (1595) 957 3490

Fodder for thought

A recent study shows the slow adoption of conservation agriculture practices in sub-Saharan Africa, despite their multiple benefits for smallholder farmers. In Zimbabwe, it is estimated that no more than 2.5% of cropland is cultivated under conservation agriculture principles.

One of the constraints is the lack of appropriate machinery and tools that reduce drudgery. “Addressing a wide set of complementary practices, from nutrient and weed management and judicious choice of crop varieties to labor demand, is key to making conservation agriculture profitable and feasible for a greater number of farmers,” said Christian Thierfelder, Principal Scientist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Farmers in the district of Murehwa, in Zimbabwe’s Mashonaland East Province, have embraced sustainable farming systems. They are benefitting from higher yields and new sources of income, and they are improving soil fertility.

Cosmas and Netsai Garwe’s homestead copes well despite the erratic weather. They own a lush one-acre field of maize and well-fed livestock: 18 cows, 9 goats and 45 free-range chickens. Two years after a crop-livestock integration initiative funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) ended, the family still benefits from the conservation agriculture practices they learnt.

“We were taught the value of minimum tillage using direct seeding, rotation, mulching and weeding to ensure that our maize crop thrived,” explained Cosmas Garwe. “Intercropping and crop rotation with legumes like soybean, pigeon pea and velvet beans really improved our soil,” said Netsai Garwe.

Like the Garwes, more than 2,000 farmers in Murehwa district are scaling the production of lablab and velvet beans, which implies almost complete adoption. Effective extension support, local innovation platforms, and access to profitable crop and livestock markets have been key drivers for widespread adoption.

Better soil and cash cows

Many of these smallholder farmers’ fields have been under cultivation for generations and the granitic sandy soils, predominant in the area, have become very poor in soil organic matter, a key component of soil fertility.

“Nitrogen-fixing green manure cover crops such as velvet beans, lablab and jack beans can provide an affordable way for smallholder farmers to bring back soil fertility, especially nitrogen, into the soil,” explained Thierfelder. “Once the soils become responsive to mineral fertilizer again, a combination of leguminous crop rotations, manure use and in-organic fertilizer will provide stable and sustained crop yields of maize, their main food crop, even under a changing climate.”

Starting the second year the Garwes tried conservation agriculture on a 0.4-hectare plot, their yields improved, realizing 1.2 tons. As an additional benefit, the cover crops could be used as new animal feed sources, so they could keep maize crop residues as soil cover and increase the amount of organic matter in the soils.

Adoption of green manure cover crops was not easy at first, but farmers from Murehwa quickly realized that lablab and velvet beans improved the fattening of cattle and poultry. Drying the cover crop, they were able to produce protein-rich hay bales, sought-after in winter when other fodder stocks usually run low.

Better-fed, healthier animals meant better sales, as the Garwes could now get around $1,200 for one cow. Neighboring farmers soon found this new crop-livestock system appealing and joined the initiative.

Saving for a dry day

The economic opportunities for farmers in Murehwa go beyond cow sales. In 2013, the Klein Karoo (K2) seed company offered contracts to farmers for the production of lablab seed. Suddenly the crop became highly profitable, which trigged adoption by almost all the farmers in the area.

As explained by extension officer Ngairo, “there is lablab and velvet beans grown everywhere, at homestead plots, school gardens… using ripline seeding techniques and showing the widespread adoption of conservation agriculture practices in the ward.”

Better incomes from livestock, fodder and lablab seeds had ripple effects for these Murehwa communities.

Since they adopted lablab and conservation agriculture practices in 2013, Kumbirai and Lilian Chimbadzwa transformed their asset base. They were able to complete their four-bedroom house, connect their homestead with the national electricity network and send their daughter to a nearby boarding school.

Despite prolonged dry spells during the last season and the threat of fall armyworm, these farmers have been coping much better than those practicing conventional tillage farming.

“Farmers taking up lablab and other leguminous cover crops have not only improved their incomes, but also the resilience of their farming systems,” explained Isaiah Nyagumbo, Cropping Systems Agronomist at CIMMYT. “Conservation agriculture practices such as mulching help retain soil moisture, while pests and diseases are less prominent in diversified fields planted with stress tolerant maize varieties and legume cover crops.”

For CIMMYT and other institutions willing to scale sustainable intensification practices in Africa, there is plenty to learn from the farmers in Murehwa.

New research in the district has started to test how climate-adapted push-pull systems support smallholder farmers in overcoming the invasive fall armyworm using biological means. These systems involve conservation agriculture, green manure and legume intercropping, and planting high-productivity fodders surrounding the plots. This would also reduce the reliance on pesticides, which may be harmful for humans and the environment.

Bangladesh increases efforts to fight fall armyworm

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute (BWMRI), organized a training on fall armyworm on April 25, 2019 at the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council (BARC). Experts discussed the present outbreak status, progress on strategic research, and effective ways to control this destructive pest.

The event featured Dan McGrath, Entomologist and Professor Emeritus at Oregon State University, and Joseph Huesing, Senior Biotechnology Advisor and Program Area Lead for Advanced Approaches to Combating Pests and Diseases at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Also attending were senior officials from Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI), Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU), Department of Agricultural Extension, BARC, BWMRI and CIMMYT.

“Fall armyworm cannot be eradicated. It is endemic and farmers have to learn to manage it,” said Huesing in his overview of the fall armyworm infestation in Africa. He also mentioned that fall armyworm is generally followed by southern armyworm, so Bangladesh will need a strategy for managing multiple pests.

“Fall armyworm cannot be eradicated. It is endemic and farmers have to learn to manage it.”

— Joseph Huesing, USAID

Huesing explained that an effective approach for controlling fall armyworm and other pests is “knowledge, tools and policy.”

According to Huesing, Bangladeshi farmers have adequate knowledge about the pest and how to control it, especially compared to African farmers. The next step is securing the necessary tools to control fall armyworm, like spraying their fields with necessary insecticides by authorized personnel. Huesing emphasized the importance of appropriate policy implementation, particularly to ensure the registration of the right kind of insecticides assigned to effectively control fall armyworm.

Fall armyworm is a fast-reproducing species that can attack crops and cause devastation almost overnight. Even though the level of infestation in Bangladesh is still relatively light, more than 80 varieties of crops have already been attacked in 22 districts within just a few months.

Huesing indicated that safer options included handpicking of the pest, treating seeds, pheromone traps, flood irrigation and crop rotation. Currently, to help farmers learn more about the pest, the Department of Agricultural Extension is distributing factsheets and conducting awareness-raising workshops in different villages.

McGrath focused on the long-term management of fall armyworm and how Bangladesh can learn from the experience of Africa in order to avoid the same errors. McGrath suggested that weather forecasts were an important tool for helping determine when and where outbreaks might occur. Training relevant personnel is also a crucial aspect of reining in this plague. “Training the trainers has to be hands on. We need to put more emphasis on the field than on the classroom,” McGrath said.

This workshop was part of the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA).

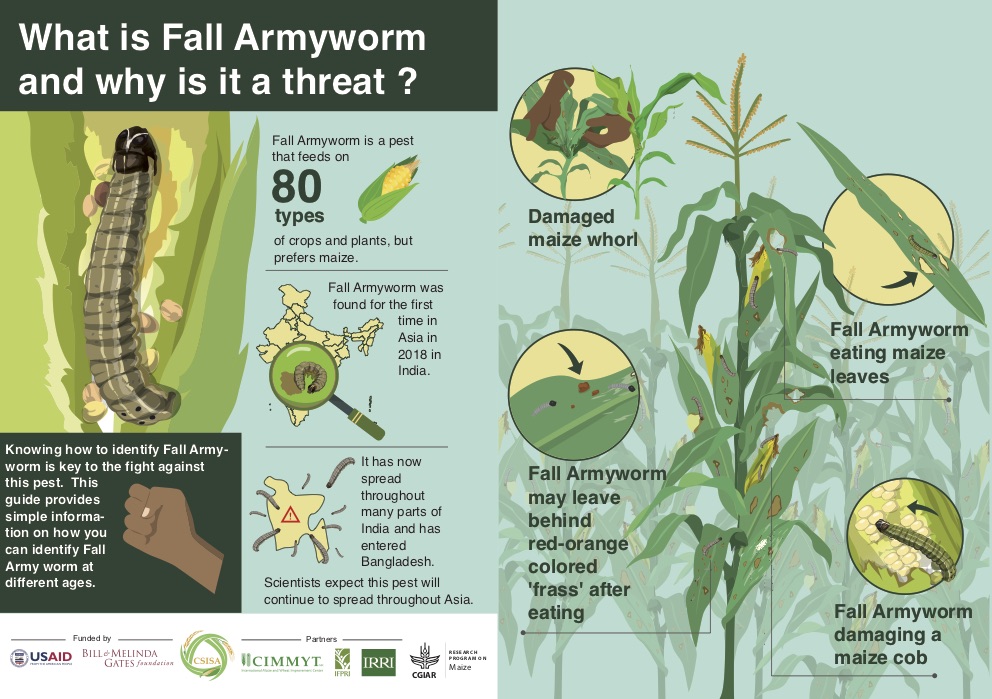

The fall armyworm, explained

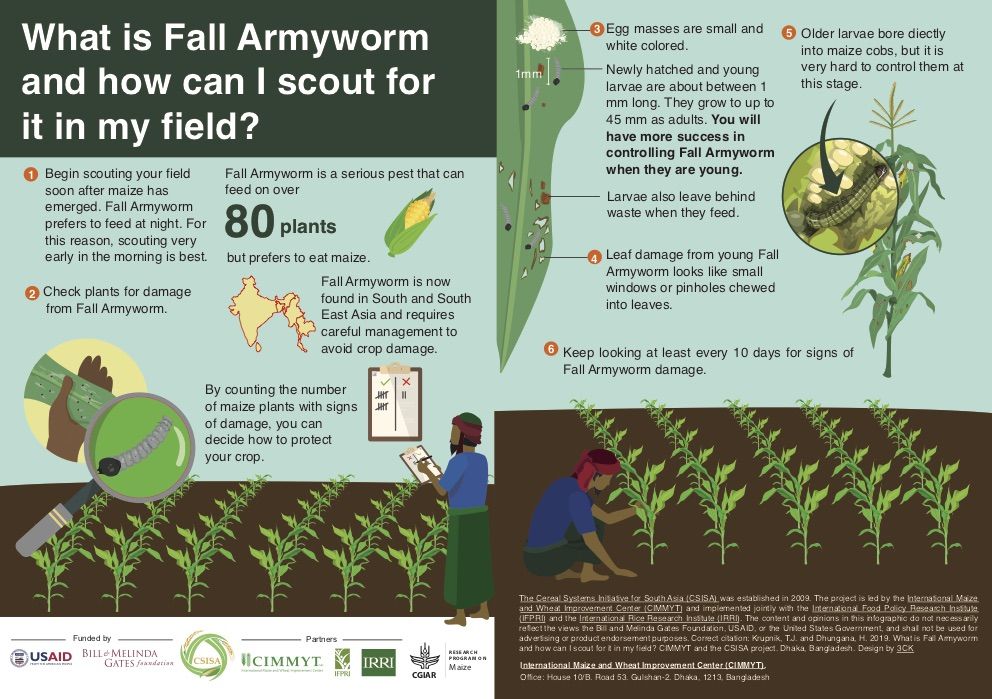

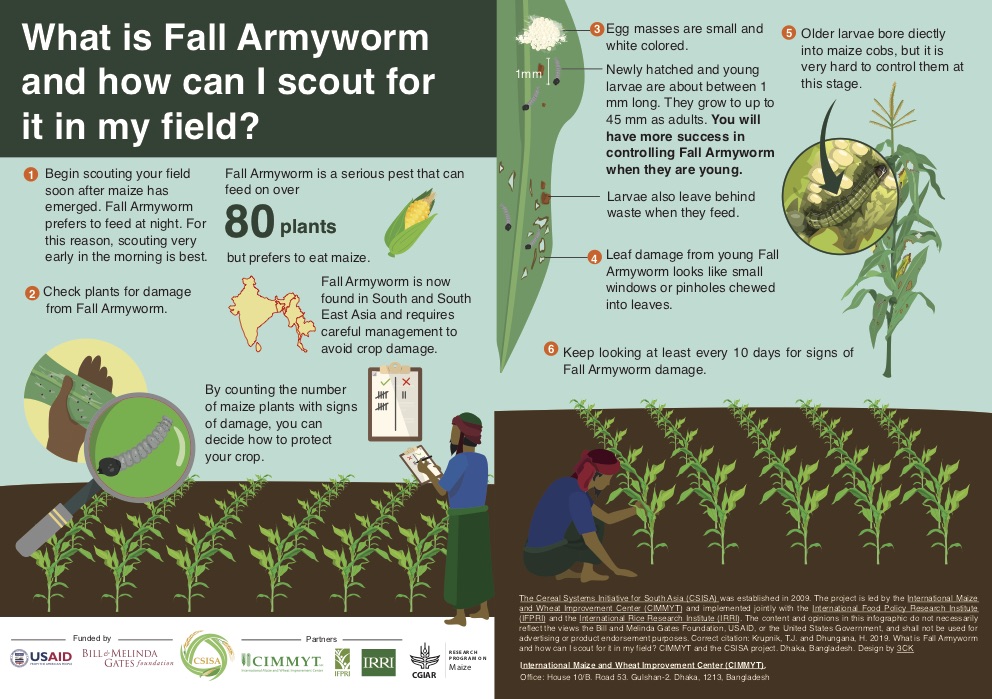

As part of the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) has created a series of infographics explaining key information about fall armyworm.

These infographics will be translated and used to reach out to farmers in Bangladesh, through agrodealers and public sector partners. The principles and concepts presented in them — which champion the use of integrated pest management strategies — are relevant to countries across the region.

If you would like to use these infographics in other countries or translate them to other languages, please contact Tim Krupnik.

Fall armyworm is an invasive insect pest that can eat 80 different types of plants, but prefers maize. It spread throughout Africa in just two years, and was found in India in late 2018. Since then it has spread across South and South East Asia, where it presents a serious threat to food and income security for millions of smallholder farmers.

Fall armyworm is an invasive insect pest that can eat 80 different types of plants, but prefers maize. It spread throughout Africa in just two years, and was found in India in late 2018. Since then it has spread across South and South East Asia, where it presents a serious threat to food and income security for millions of smallholder farmers.

The infographics are designed to be printed as foldable cards that farmers can carry in their pocket for easy reference. The graphics provide an overview of fall armyworm biology as well as the insect’s ecology and lifecycle. They also describe how to identify and scout maize fields for fall armyworm and provide easy-to-follow recommendations for what to do if thresholds for damage are found. One of the infographics provides farmers with ideas on how to manage fall armyworm in their field and village, including recommendations for agronomic, agroecological, mechanical and biological pest management. In addition, chemical pest management is presented in a way that informs farmers about appropriate safety precautions if insecticide use is justified.

How can I identify fall armyworm?

Conservation agriculture works for farmers and for sustainable intensification

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) and the Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Southern Africa (ASARECA) gathered agriculture leaders, experts, ministers and permanent secretaries from 14 countries in the region May 2-4, 2019 in Kampala, Uganda. These experts reflected on the lessons learned from the eight year-long Sustainable Intensification of Maize and Legumes farming systems in Eastern and Southern Africa (SIMLESA) project, funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR).

During this regional SIMLESA policy forum, ministers of agriculture signed a joint communiqué calling for mainstreaming conservation agriculture practices and enabling sustainable intensification of African agriculture, in response to the ongoing agroecological crisis and fast-growing population.

The minister of agriculture, animal industry and fisheries of Uganda, Vincent Ssempijja, reminded that “Africa is paying a high price from widespread land degradation, and climate change is worsening the challenges smallholder farmers are facing.” Staple crop yields are lagging despite a wealth of climate-smart technologies like drought-tolerant maize varieties or conservation agriculture.

“It is time for business unusual,” urged guest speaker Kirunda Kivejinja, Uganda’s Second Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of East African Affairs.

Research conducted by CIMMYT and national partners in Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda under the SIMLESA project provided good evidence that sustainable intensification based on conservation agriculture works — it significantly increased food crop yields, up to 38%, as well as incomes, while sustainably preserving soil health.

In Malawi, where conservation agriculture adoption rose from 2% in 2011 to 35% in the 2017/18 season, research showed increases in water infiltration compared to the conventional ridge-and-furrow system of up to 90%, while soil organic carbon content increased by 30%. This means that soil moisture is better retained after rainfall, soil is more fertile, and plants grow well and cope much better during dry spells.

The SIMLESA project revealed that many farmers involved in CIMMYT research work, like Joseph Ntirivamunda in Rwanda, were interested in shifting towards more sustainable intensification practices. However, large-scale adoption still faces many hurdles.

“You cannot eat potential,” pointed out CIMMYT scientists and SIMLESA project leader Paswel Marenya. “The promise of conservation agriculture for sustainable intensification needs to be translated into more food and incomes, for farmers to adopt it widely.”

The scale conundrum

Farmers’ linkages to markets and services are often weak, and a cautious analysis of trade-offs is necessary. For instance, more research is needed about the competing uses of crop residues for animal feed or soil cover.

Peter Horne, General Manager for ACIAR’s global country programs, explained that science has an important role in informing policy to drive this sustainable transformation. There are still important knowledge gaps to better understand what drives key sustainable farming practices. Horne advised to be more innovative than the traditional research-for-development and extension approaches, involving for instance the private sector.

Planting using a hoe requires 160 hours of labor per hectare. A two-wheel tractor equipped with a planter will do the same work in only 3 hours.

One driver of change that was stressed during the Kampala forum was the access to appropriate machinery, like the two-wheel tractor equipped with a direct planter. While hoe planting requires 160 hours of labor per hectare, the planter needs only 3 hours per hectare, enabling timely planting, a crucial factor to respond effectively to the increased vagaries of the weather and produce successful harvests. While some appropriate mechanization options are available at the pilot stage in several African countries like Ethiopia or Zimbabwe, finding the right business models for service provision for each country is key to improve access to appropriate tools and technologies for smallholder farmers. CIMMYT and ACIAR seek to provide some answers through the complementary investments in the Farm Mechanization and Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Intensification (FACASI) project.

CASI can be scaled but requires tailoring sustainable intensification agronomic advices adapted to local environment and farming systems. Agricultural innovation platforms like the Mwanga mechanization youth group in Zimbabwe are one way to co-create solutions and opportunities between specific value chain actors, addressing some of the constraints farmers may face while implementing conservation agriculture practices.

Providing market incentives for farmers has been one challenging aspect, which may be overcome through public-private partnerships. Kilimo Trust presented a new consortium model to drive sustainable intensification through a market pull, linking smallholder farmers with food processors or aggregators.

“SIMLESA, as a long-term ambitious research program, has delivered remarkable results in diverse farming contexts, and conservation agriculture for sustainable intensification now has a more compelling case,” said Eric Huttner, ACIAR research program manager. “We should not ignore the complexity of conservation agriculture adoption, as shifting to new farming practices brings practical changes and potential risks for farmers, alongside benefits,” he added. As an immediate step, Huttner suggested research to define who in the public and private sectors is investing and for what purpose — for example, access to seed or machinery. Governments will also need further technical support to determine exactly how to mainstream conservation agriculture in future agricultural policy conversations, plans and budgets.

“Looking at SIMLESA’s evidence, we can say that conservation agriculture works for our farmers,” concluded Josefa Leonel Correia Sacko, Commissioner for Rural Economy and Agriculture of the African Union. During the next African Union Specialized Technical Committee in October 2019, she will propose a new initiative, scaling conservation agriculture for sustainable intensification across Africa “to protect our soils and feed our people sustainably.”

Shifting to a demand-led maize improvement agenda

Partners of the Stress Tolerant Maize for Africa (STMA) project held their annual meeting May 7–9, 2019, in Lusaka, Zambia, to review the achievements of the past year and to discuss the priorities going forward. Launched in 2016, the STMA project aims to develop multiple stress-tolerant maize varieties for diverse agro-ecologies in sub-Saharan Africa, increase genetic gains for key traits preferred by the smallholders, and make these improved seeds available at scale in the target countries in partnership with local public and private seed sector partners.

The project, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), is led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), and implemented together with the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA), national agricultural research systems and seed company partners in 13 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

The meeting was officially opened by the Deputy Director of the Zambia Agriculture Research Institute (ZARI), Monde Zulu. “Maize in Africa faces numerous challenges such as drought, heat, pests and disease. Thankfully, these challenges can be addressed through research. I would like to take this opportunity to thank CIMMYT and IITA. Your presence here is a testament of your commitment to improve the livelihoods of farmers in sub-Saharan Africa,” she said.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and its partners are working together in the fight against challenges such as drought, maize lethal necrosis and fall armyworm. The STMA project applies innovative technologies such as high-throughput phenotyping, doubled haploids, marker-assisted breeding and intensive germplasm screening to develop improved stress-tolerant maize varieties for smallholder farmers. The project team is also strengthening maize seed systems in sub-Saharan Africa through public-private partnerships.

The efforts are paying off: in 2018, 3.5 million smallholder farmers planted stress-tolerant maize varieties in 10 African countries.

Yielding results

CIMMYT researcher and STMA project leader Cosmos Magorokosho reminded the importance of maize in the region. “Maize is grown on over 35 million hectares in sub-Saharan Africa, and more than 208 million farmers depend on it as a staple crop. However, average maize yields in sub-Saharan Africa are among the lowest in the world.” Magorokosho pointed out that the improved maize varieties developed through the project “provide not only increased yields but also yield stability even under challenging conditions like drought, poor soil fertility, pests and diseases.”

“STMA has proved that it is possible to combine multiple stress tolerance and still get good yields,” explained B.M. Prasanna, director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program and the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE). “One of the important aspects of STMA are the partnerships which have only grown stronger through the years. We are the proud partners of national agricultural research systems and over 100 seed companies across sub-Saharan Africa.”

Keynote speaker Hambulo Ngoma of the Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute (IAPRI) addressed the current situation of maize in Zambia, where farmers are currently reeling from recent drought. “Maize is grown by 89% of smallholder farmers in Zambia, on 54% of the country’s cultivable land, but productivity remains low. This problem will be exacerbated by expected population growth, as the population of Zambia is projected to grow from over 17 million to 42 million by 2050,” he said.

Down to business

On May 8, participants visited three partner local seed companies to learn more about the opportunities and challenges of producing improved maize seed for smallholder farmers.

Afriseed CEO Stephanie Angomwile discussed her business strategy and passion for agriculture with participants. She expressed her gratitude for the support CIMMYT has provided to the company, including access to drought-tolerant maize varieties as well as capacity development opportunities for her staff.

Bhola Nath Verma, principal crop breeder at Zamseed, explained how climate change has a visible impact on the Zambian maize sector, as the main maize growing basket moved 500 km North due to increased drought. Verma deeply values the partnership with the STMA project, as he can source drought-tolerant breeding materials from CIMMYT and IITA, allowing him to develop early-maturing improved maize varieties that escape drought and bring much needed yield stability to farmers in Angola, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Zambia.

At QualiBasic Seed, STMA partners were given the opportunity to learn and ask questions about the company’s operations, including the seed multiplication process in Zambia and the importance of high-quality, genetically pure foundation seed for seed companies.

Young ideas

The meeting concluded with an awards ceremony for the winners of the 2019 MAIZE Youth Innovators Awards – Africa, established by MAIZE in collaboration with the Young Professionals for Agricultural Development (YPARD). These awards recognize the contributions of young women and men under 35 who are implementing innovations in African maize-based agri-food systems, including research-for-development, seed systems, agribusiness, and sustainable intensification. This is the second year of the MAIZE Youth Awards, and the first time it has been held in Africa. Winners include Hildegarde Dukunde of Rwanda and Mila Lokwa Giresse of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the change agent category, Admire Shayanowako of the Republic of South Africa and Ismael Mayanja of Uganda in the research category, and Blessings Likagwa of Malawi in the farmer category.

Breaking Ground: Mechanization expert Jelle Van Loon goes as far as creativity allows

In November 2015, Jelle Van Loon set off for Zimbabwe, with a cross-section plan in his backpack. He spent two weeks working with a group of blacksmiths, searching Harare for parts and assembling machines in a bid to test whether the construction plans developed by his team were indeed designed to be built anywhere. “We might have had to change a few things, but three working machines were built, proving the accessibility of the construction plans and inherent replicability of the designs.”

In November 2015, Jelle Van Loon set off for Zimbabwe, with a cross-section plan in his backpack. He spent two weeks working with a group of blacksmiths, searching Harare for parts and assembling machines in a bid to test whether the construction plans developed by his team were indeed designed to be built anywhere. “We might have had to change a few things, but three working machines were built, proving the accessibility of the construction plans and inherent replicability of the designs.”

From studying agronomic engineering and crop modelling in Belgium to working on supply chain issues in Peru, Jelle Van Loon amassed a range of experience before joining the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in 2012. Soon after joining, he began shaping up a team to work on mechanization issues.

“First and foremost I’m an agricultural engineer; I just happen to have a high affinity with mechanics,” he says. “I think my advantage is having a broad knowledge, being able to understand agronomy as well as mechanical engineering, and having studied agricultural economics in developing countries.”

This background has served him well in a role where a hands-on, multidisciplinary approach is crucial.

“Mechanization doesn’t necessarily mean building or creating more machines,” Van Loon explains, “but rather introducing technology and farm equipment to farmers to facilitate their work, as well as supporting them on how and when to use it to increase production efficiency.” Many people also assume that mechanization only involves motorized equipment such as tractors, he adds, when in fact any tool, even simple hand tools, which facilitate farmer work and alleviate drudgery fit into this concept.

CIMMYT’s mechanization team carries out research and development on a range of farm equipment. Team members draw and design prototypes, test them in the field and develop protocols for experiments. Combining agronomy and mechanics, they work to create machinery that supports farmers in their day-to-day work at each stage of the crop cycle: from land preparation, planting and fertilization, to harvest and shelling. They also support the generation of new business models which can deliver appropriate machinery to farmers working within resilient agri-food systems.

One of the biggest challenges is changing the way farmers work. Many are resistant to investing in new machinery because they are unsure of how to use it, and simply cannot afford the risk of failure. As such, the team also places an emphasis on extension work. They have set up centers where growers can learn about the equipment and rent out some model machines. They also build the capacity of service providers through training on functional engineering for blacksmiths and manufacturers, and market intelligence for small sector entrepreneurs.

“It’s beyond just designing the machine. It’s really about taking products out to the field, seeing what works well and where, and then thinking about how we can get these products into the hands of farmers.”

Building on the work being carried out in Mexico, Van Loon is always looking at how other regions can also benefit from the mechanization unit and opportunities for collaborating with colleagues and partners in Africa and Asia. Equipment developed for farmers in Africa or Latin America could be adapted for use in South Asia or vice versa, but this requires a solid understanding of each region’s unique opportunities and challenges.

He points to the example of the two-wheel tractor engine, developed in China and popularized in Asia during the 1980s, when famine and the loss of draft animals prompted governments to subsidize that particular piece of equipment at the right time. The tractor is ubiquitous in countries such as Bangladesh, but it is unclear whether the same success is replicable in Africa and Latin America, neither of which has the same conditions, second-hand markets or import facilities. “We’re trying to learn from cross-regional efforts to scale up. Being able to understand different areas helps us find the weakest links and create more enabling environments,” Van Loon explains.

He and his team are continuously developing and evaluating new ideas, trialing ways of embedding mechatronics or sensory-based technology into their machines to help capture data and ease farmer workloads. Finding a way to keep these low-cost and convenient for farmer use may be a challenge, but positive testimonials from farmers keep him excited about the possibilities.

“I think it’s worthwhile to follow through on wild new ideas and see what happens because when it works out, the positive impact and change we help create is all that matters,” Van Loon notes.

“And more so, the cool thing about working in mechanization is we can go as far as our creativity lets us.”

New publications: Agro-ecological options for fall armyworm management

Fall armyworm, a voracious pest now present in both Africa and Asia, has been predicted to cause up to $13 billion per year in crop losses in sub-Saharan Africa, threatening the livelihoods of millions of farmers throughout the region.

“In their haste to limit the damage caused by the pest, governments in affected regions may promote indiscriminate use of chemical pesticides,” say the authors of a recent study on fall armyworm management. “Aside from human health and environmental risks,” they explain, “these could undermine smallholder pest management strategies that depend largely on natural enemies.”

Agro-ecological approaches offer culturally appropriate, low-cost pest control strategies that can be easily integrated into existing efforts to improve smallholder incomes and resilience through sustainable intensification. Researchers suggest these should be promoted as a core component of integrated pest management programs in combination with crop breeding for pest resistance, classical biological control and selective use of safe pesticides.

However, the suitability of agro-ecological measures for reducing fall armyworm densities and impact must be carefully assessed across varied environmental and socioeconomic conditions before they can be proposed for wide-scale implementation.

To support this process, researchers at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) reviewed evidence for the efficacy of potential agro-ecological measures for controlling fall armyworm and other pests, consider the associated risks and draw attention to critical knowledge gaps. Findings from the Africa-wide study indicate that several measures can be adopted immediately, such as sustainable soil management, intercropping with appropriately selected companion plants and the diversification of farm environments through management of habitats at multiple spatial scales.

Read the full article “Agro-ecological options for fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith) management: Providing low-cost, smallholder friendly solutions to an invasive pest” in the Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 243, 1 August 2019, pages 318-330.

Read more recent publications by CIMMYT researchers:

- Impact of conservation tillage in rice–based cropping systems on soil aggregation, carbon pools and nutrients. 2019. Rajiv Nandan, Vikram Singh, Sati Shankar Singh, Kumar, V., Kali Krishna Hazra, Chaitanya Prasad Nath, Poonia, S. P., Malik, R.K., Ranjan Bhattacharyya, McDonald, A. In: Geoderma v. 340, p. 104-114.

- Integrating genomic-enabled prediction and high-throughput phenotyping in breeding for climate-resilient bread wheat. 2019. Juliana, P., Montesinos-Lopez, O.A., Crossa, J., Mondal, S., Gonzalez-Perez, L., Poland, J., Huerta-Espino, J., Crespo-Herrera, L.A., Velu, G., Dreisigacker, S., Shrestha, S., Perez-Rodriguez, P., Pinto Espinosa, F., Singh, R.P. In: Theoretical and Applied Genetics v. 132, no. 1, p. 177-194.

- Modeling copy number variation in the genomic prediction of maize hybrids. 2019. Hottis Lyra, D., Galli, G., Couto Alves, F., Granato, I.S.C., Vidotti, M.S., Bandeira e Sousa, M., Morosini, J.S., Crossa, J., Fritsche-Neto, R. In: Theoretical and Applied Genetics v. 132, no. 1, p. 273-288.

- Soil dwelling beetle community response to tillage, fertilizer and weeding intensity in a sub-humid environment in Zimbabwe. 2019. Mashavakure, N., Mashingaidze, A.B., Musundire, R., Nhamo, N., Gandiwa, E., Thierfelder, C., Muposhi, V.K. In: Applied Soil Ecology v. 135, p. 120-128.

- Two main stripe rust resistance genes identified in synthetic-derived wheat line soru#1. 2019. Ruiqi Zhang, Singh, R.P., Lillemo, M., Xinyao He., Randhawa, M.S., Huerta-Espino, J., Singh, P.K., Zhikang Li, Caixia Lan. In: Phytopathology v. 109, no. 1, p. 120-126.