Pulses, cobs and a healthy soil prove the success of a rural innovator

Mary Twaya is an exemplary farmer in Lemu, a rural drought-prone community in southern Malawi, near Lake Malombe. On her one-hectare farm she grows cotton, maize, and legumes like groundnut and cowpea, which she just picked from her fields. Since agriculture is Twaya’s sole livelihood, it is important for her to get good harvests, so she can support her three children and her elderly mother. She is the only breadwinner since her husband left to sell coffee in the city and never returned.

Agriculture is critically important to the economy and social fabric of Malawi, one of the poorest countries in the World. Up to 84% of Malawian households own or cultivate land. Yet, gender disparities mean that farmland managed by women are on average 25% less productive than men. Constraints include limited access to inputs and opportunities for capacity building in farming.

Climate change may worsen this gender gap. Research from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) shows that there are multidimensional benefits for women farmers to switch to climate-smart agriculture practices, such as planting drought-tolerant maize varieties and conservation agriculture with no tillage, soil cover and crop diversification.

Twaya was part of a CIMMYT project that brought climate-smart agriculture practices to smallholder farmers in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

She was enthusiastic about adopting climate-smart agriculture practices and conservation agriculture strategies in her plot. “I have always considered myself an active farmer, and when my husband left, I continued in the project around 2007 as part of the six lead ‘mother farmers’ with about 30 more ‘baby farmers’ learning through our field trials,” Twaya explained.

“We worked in Lemu since 2007 with Patrick Stanford, a very active and dedicated extension officer who introduced conservation agriculture to the village,” said CIMMYT agronomist Christian Thierfelder. “Farmers highlighted declining yields. The Lemu community was keen to transform their farming system, from conventional ridge tillage to more sustainable and climate-adapted cropping systems.” This was an ideal breeding ground for new ideas and the development of climate-smart solutions, according to Thierfelder.

Mulching, spacing and legume diversification

Showing her demonstration plot, which covers a third of her farm, Twaya highlights some of the climate-smart practices she adopted.

“Mulching was an entirely new concept to me. I noticed that it helps with moisture retention allowing my crops to survive for longer during the periods of dry spells. Compared to the crops without mulching, one could easily tell the difference in the health of the crop.”

“Thanks to mulching and no tillage, a beneficial soil structure is developed over time that enables more sustained water infiltration into the soil’’, explained Thierfelder. “Another advantage of mulching is that it controls the presence of weeds because the mulch smothers weeds unlike in conventional systems where the soil is bare.”

Research shows that conservation agriculture practices like mulching, combined with direct seeding and improved weed control practices, can reduce an average of 25-45 labor days per hectare for women and children in manual farming systems in eastern Zambia and Malawi. This time could be used more productively at the market, at home or in other income-generating activities.

After 12 years of practicing conservation agriculture, Twaya confirms that she does not spend too much time in the field because she just uproots the weeds with no need for using a hoe. This makes the weeding task less laborious and allows her to spend her time on other chores such as fetching water, washing laundry or cleaning her homestead. “I have time to also go to the village banking and loan savings club to meet with others”.

Adopting optimum plant density, instead of throwing in three seeds in each planting hole was another transformational change. The “Sasakawa spacing” — where maize seeds are planted 25 centimeters apart in rows spaced every 75 centimeters — saves seed and boosts yields, as each plant receives adequate fertilizer, light and water without competing with the other seeds. This practice was introduced in Malawi in the year 2000 by Sasakawa Global.

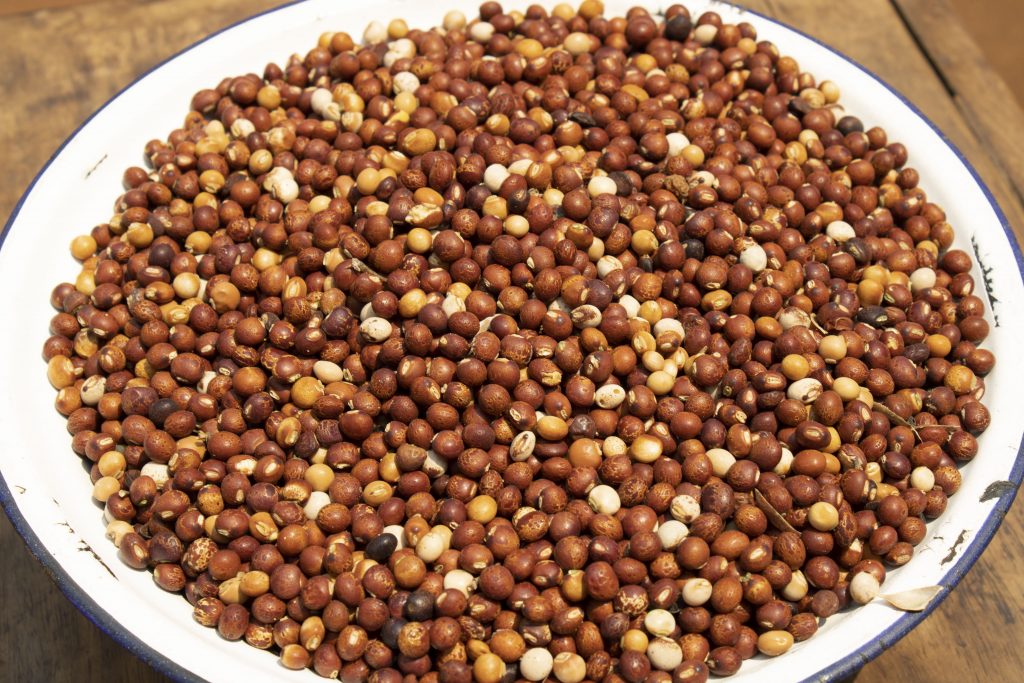

Twaya pays more attention to the benefits of planting nitrogen-fixing crops alongside her maize, as she learned that “through crop rotation, legumes like pigeon pea improve the nutrition of my soil.” In the past she threw pigeon pea seeds loosely over her maize field and let it grow without any order, but now she practices a “double-up legume system,” where groundnut and pigeon pea are cropped at the same time. Pigeon peas develop slowly, so they can grow for three months without competition after groundnut is harvested. This system was introduced by the Africa RISING project, funded by USAID.

A mother farmer shows the way

Switching to climate-smart agriculture requires a long-term commitment and knowledge. Some farmers may resist to the changes because they initially find it new and tedious but, like Twaya observed, “it may be because they have not given themselves enough time to see the long-term benefits of some of these practices.”

With all these innovations — introduced in her farm over the years with the support of CIMMYT and the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development of Malawi — Twaya reaped important economic and social benefits.

When Twaya rotates maize and pigeon pea, the maize stalks are healthy and the cobs are big, giving her higher yields. Passing-by neighbors will often exclaim ‘‘Is this your maize?’’ because they can tell it looks much more vigorous and healthier than what they see in other fields.

For the last season, Twaya harvested 15 bags of 50kg of maize from her demo plot, the equivalent of five tons per hectare. In addition to her pigeon pea and groundnut crops, she was able to feed her family well and earned enough to renovate her family home this year.

This new way of managing her fields has gained Twaya more respect and has improved her status in the community.