Smartphones drive data collection revolution, boost climate-smart agriculture in Bangladesh

Agricultural research is entering a new age in Bangladesh. The days, months and years it takes to collect farm data with a clipboard, paper and pen are nearing their end.

Electronic smartphones and tablets are gaining ground, used by researchers, extension workers and farmers to revolutionize the efficiency of data collection and provide advice on best-bet practices to build resilient farming systems that stand up to climate change.

Digital data collection tools are crucial in today’s ‘big data’ driven agricultural research world and are fundamentally shifting the speed and accuracy of agricultural research, said Timothy Krupnik, Senior Scientist and Systems Agronomist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

“Easy-to-use data collection tools can be made available on electronic tablets for surveys. These allow extension workers to collect data from the farm and share it instantaneously with researchers,” he said.

“These tools allow the regular and rapid collection of data from farmers, meaning that researchers and extension workers can get more information than they would alone in a much quicker time frame.”

“This provides a better picture of the challenges farmers have, and once data are analyzed, we can more easily develop tailored solutions to farmers’ problems,” Krupnik explained.

Through the USAID and Bill and Melinda Gates supported Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) supported Big Data Analytics for Climate-Smart Agriculture in South Asia projects, 125 Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) agents were trained throughout Bangladesh to use tablets to gather agronomic information from rice and wheat farmers.

It is the first time extension workers have been involved in data collection in the country. Since the pilot began in late 2019, extension workers have collected data from over 5,000 farmers, with detailed information on climate responses, including the management of soil, water and variety use to understand what drives productivity. The DAE is enthused about learning from the data, and plans to collect information from 7,000 more farmers in 2020.

Bangladesh’s DAE is directly benefiting through partnerships with expert national and international researchers developing systems to efficiently collect and analyze massive amounts of data to generate relevant climate-smart recommendations for farmers, said the department Director General Dr. M. Abdul Muyeed.

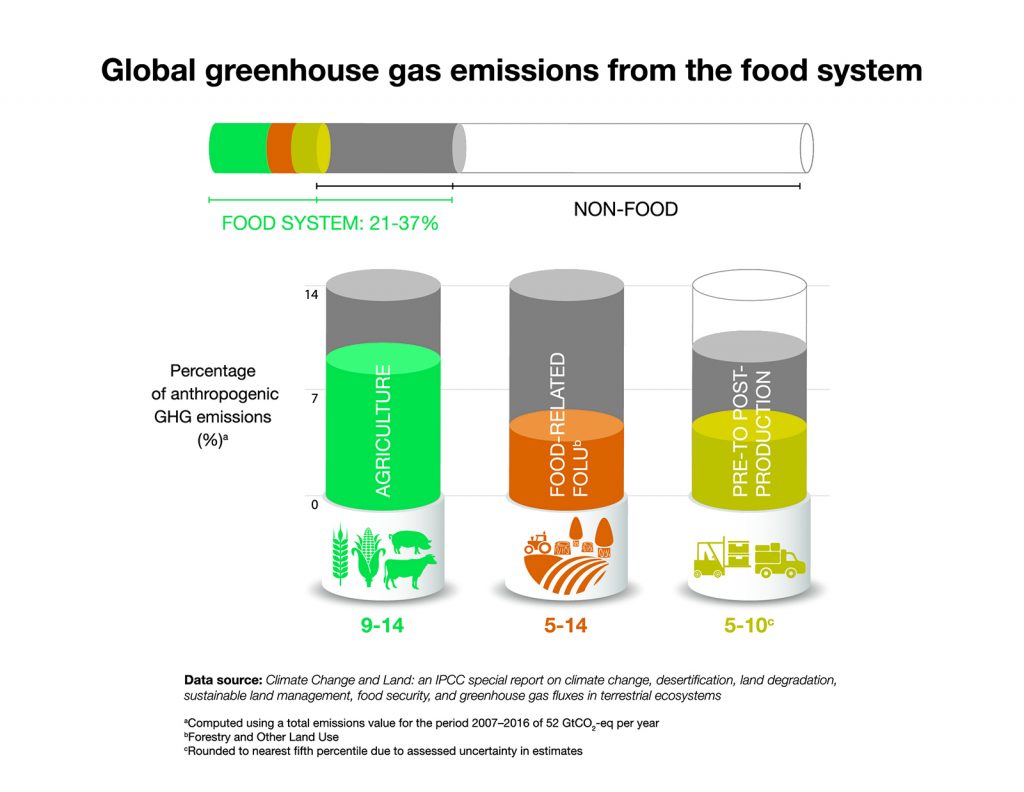

For the first time widespread monitoring examines how farmers are coping with climate stresses, and agronomic data are being used to estimate greenhouse gas emissions from thousands of individual farmers. This research and extension partnership aims at identifying ways to mitigate and adapt to climate change, he explained.

“This work will strengthen our ability to generate agriculturally relevant information and increase the climate resilience of smallholder farmers in Bangladesh,” Dr. Muyeed said.

Next-gen big data analysis produces best-bet agricultural practices

“By obtaining big datasets such as these, we are now using innovative research methods and artificial intelligence (AI) to examine patterns in productivity, the climate resilience of cropping practices, and greenhouse gas emissions. Our aim is to develop and recommend improved agricultural practices that are proven to increase yields and profitability,” said Krupknik.

The surveys can also be used to evaluate on-farm tests of agricultural technologies, inform need-based training programs, serve local knowledge centers and support the marketing of locally relevant agricultural technologies, he explained.

“Collecting farm-specific data on greenhouse gas emissions caused by agriculture and recording its causes is a great step to develop strategies to reduce agriculture’s contribution to climate change,” added Krupnik.