Agriculture for Peace: A call to action to avert a global food crisis

50 years ago, the late Norman Borlaug received the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize for averting famine by increasing wheat yield potential and delivering improved varieties to farmers in South Asia. He was the first Nobel laureate in food production and is widely known as “the man who saved one billion lives.”

In the following decades, Borlaug continued his work from the Mexico-based International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), a non-profit research-for-development organization funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and the governments of Mexico and the United States.

CIMMYT became a model for a future network of publicly-funded organizations with 14 research centers: CGIAR. Today, CGIAR is led by Marco Ferrroni, who describes it as a global research partnership that “continues to be about feeding the world sustainably with explicit emphasis on nutrition, the environment, resource conservation and regeneration, and equity and inclusion.”

Norman Borlaug’s fight against hunger has risen again to the global spotlight in the wake of the most severe health and food security crises of the 21st Century. “The Nobel Peace Prizes to Norman Borlaug and the World Food Programme are very much interlinked,” said Kjersti Flogstad, Executive Director of the Oslo-based Nobel Peace Center. “They are part of a long tradition of awarding [the prize] to humanitarian work, also in accordance with the purpose [Alfred] Nobel expressed in his last will: to promote fraternity among nations.”

During welcome remarks at the virtual 50-year commemoration of Norman Borlaug’s Nobel Peace Prize on December 8, 2020, Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development Víctor Villalobos Arámbula, warned that “for the first time in many years since Borlaug defeated hunger in Southeast Asia, millions of people are at risk of starvation in several regions of Africa, Asia and Latin America.”

According to CIMMYT’s Director General Martin Kropff, celebrating Norman Borlaug’s legacy should also lead to renewed investments in the CGIAR system. “A report on the payoff of investing in CGIAR research published in October 2020 shows that CIMMYT’s return on investment (ROI) exceeds a benefit-cost ratio of 10 to 1, with median ROI rates for wheat research estimated at 19 and for maize research at 12.”

Mexico’s Foreign Affairs Department echoed the call to invest in Agriculture for Peace. “The Government of Mexico, together with the Nobel Peace Center and CIMMYT, issues a joint call to action to overcome the main challenges to human development in an international system under pressure from conflict, organized crime, forced migration and climate change,” said Martha Delgado, Mexico’s Under Secretary of Multilateral Affairs and Human Rights.

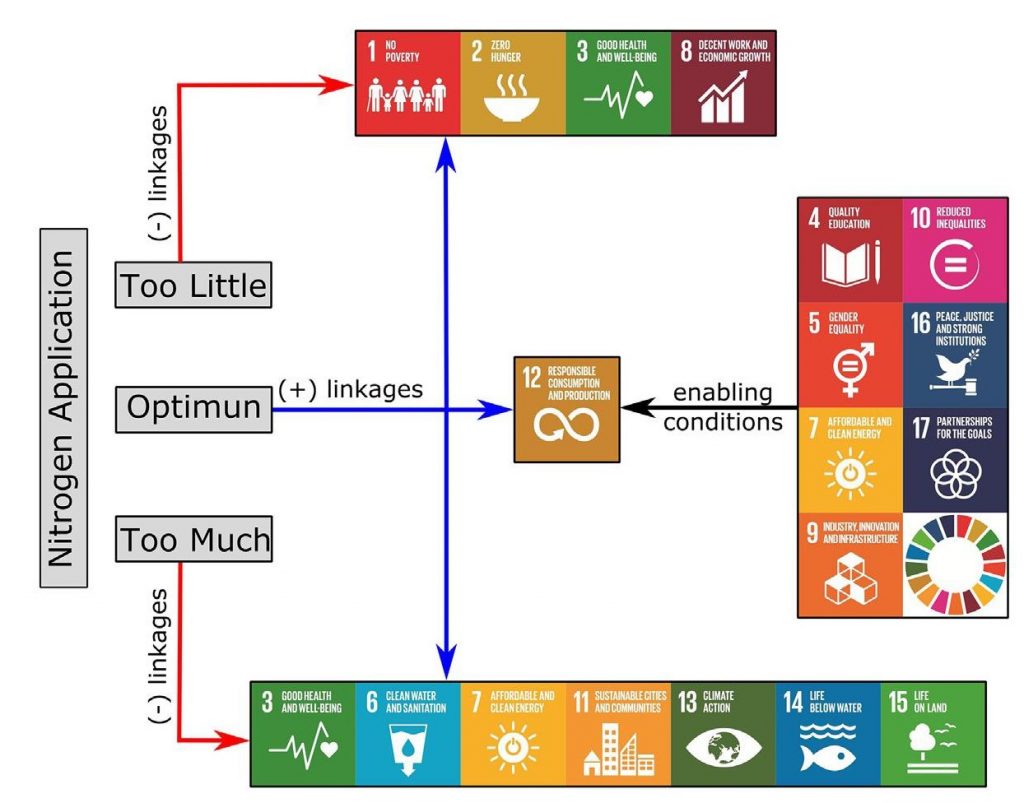

The event called for action against the looming food crises through the transformation of food systems, this time with an emphasis on nutrition, environment and equality. Speakers included experts from CGIAR, CIMMYT, Conservation International, Mexico’s Agriculture and Livestock Council, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Food Programme (WFP), among others. Participants discussed the five action tracks of the 2021 United Nations Food Systems Summit: (1) ensure access to safe and nutritious food for all; (2) shift to sustainable consumption patterns; (3) boost nature-positive production; (4) advance equitable livelihoods; and, (5) build resilience to vulnerabilities, shocks and stresses.

“This event underlines the need for international solidarity and multilateral cooperation in the situation the world is facing today,” said Norway’s Ambassador to Mexico, Rut Krüger, who applauded CIMMYT’s contribution of 170,000 maize and wheat seeds to the Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, Norway. “This number reflects the global leadership position of CIMMYT in the development of maize and wheat strains.”

Norman Borlaug’s famous words — “take it to the farmer” — advocated for swift agricultural innovation transfers to the field; Julie Borlaug, president of the Borlaug Foundation, said the Agriculture for Peace event should inspire us to also “take it to the public.”

“Agriculture cannot save the world alone,” she said. “We also need sound government policies, economic programs and infrastructure.”

CIMMYT’s Deputy Director General for Research and Partnerships, and Integrated Development Program Director Bram Govaerts, called on leaders, donors, relief and research partners to form a global coalition to transform food systems. “We must do a lot more to avert a hunger pandemic, and even more to put the world back on track to meet the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda.”

CIMMYT’s host country has already taken steps in this direction with the Crops for Mexico project, which aims to improve the productivity of several crops essential to Mexico’s food security, including maize and wheat. “This model is a unique partnership between the private, public and social sectors that focuses on six crops,” said Mexico’s Private Sector Liaison Officer Alfonso Romo. “We are very proud of its purpose, which is to benefit over one million smallholder households.”

The call stresses the need for sustainable and inclusive rural development. “It is hard to imagine the distress, frustration and fear that women feel when they have no seeds to plant, no grain to store and no income to buy basic foodstuffs to feed their children,” said Nicole Birrell, Chair of CIMMYT’s Board of Trustees. “We must make every effort to restore food production capacities and to transform agriculture into productive, profitable, sustainable and, above all, equitable food systems worldwide.”

In 1970,

In 1970,