New project to recharge aquifers and cut water use in agriculture by 30 percent

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) announced a new three-year public–private partnership with the German development agency GIZ and the beverage company Grupo Modelo (AB InBev) to recharge aquifers and encourage water-conserving farming practices in key Mexican states.

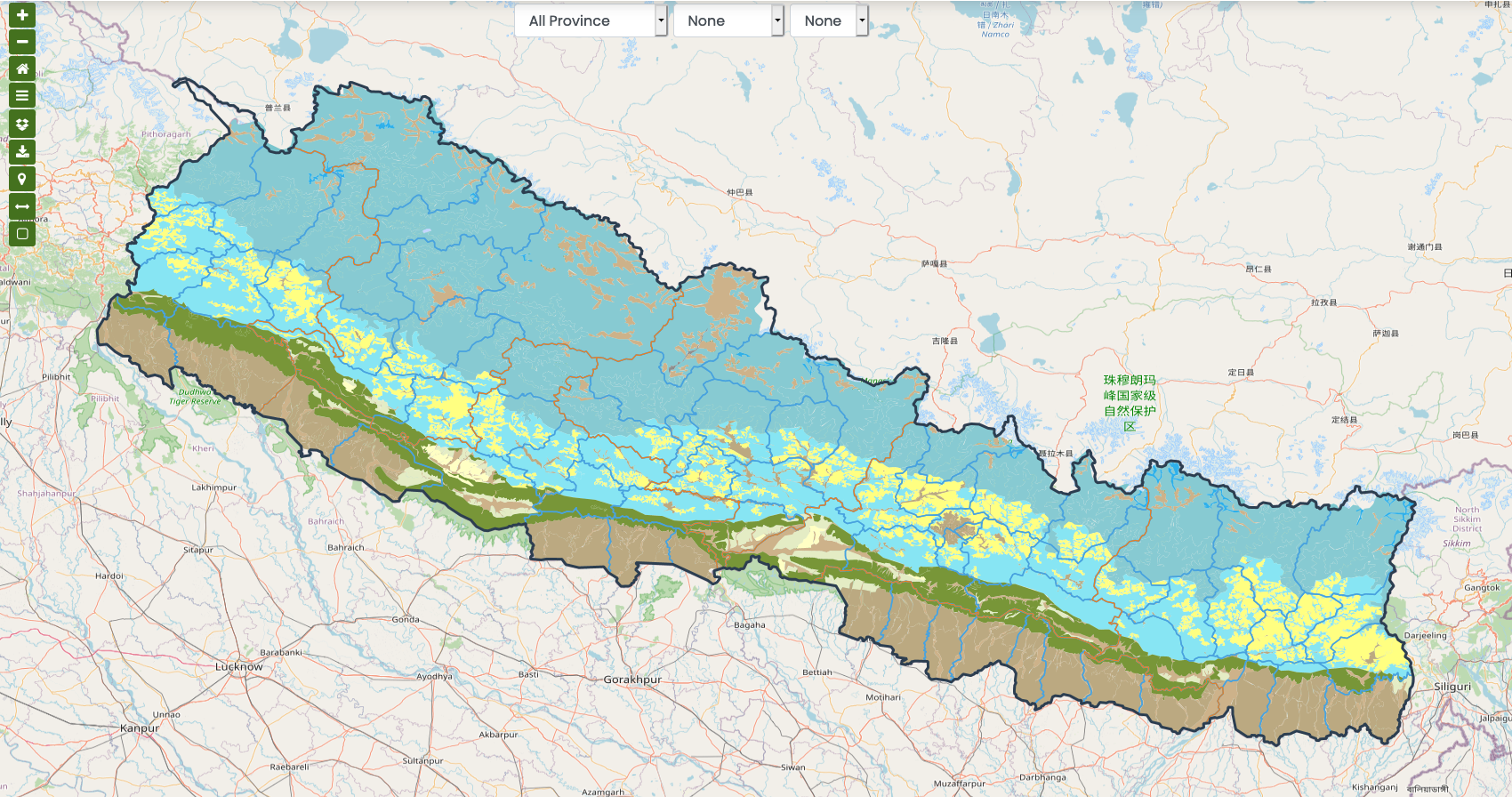

The partnership, launched today, aims to contribute to a more sustainable use of water in agriculture. The project will promote sustainable farming and financing for efficient irrigation systems in the states of Hidalgo and Zacatecas, where Grupo Modelo operates. CIMMYT’s goal is to facilitate the adoption of sustainable intensification practices on more than 4,000 hectares over the next three years, to reduce the water footprint of participant farmers.

Mexico is at a high risk of facing a water crisis in the next few years, according to the World Resources Institute. The country needs to urgently begin reducing its use of available surface and ground water supplies if it is to avert the looming crisis.

Farming accounts for nearly 76% of Mexico’s annual water consumption, as estimated by Mexico’s Water Commission (CONAGUA). Farmers, therefore, have a key role to play in a more sustainable use of this valuable natural resource.

“We need to take care of the ecosystem and mitigate agriculture’s impact on the environment to address climate change by achieving more sustainable agri-food systems,” said Bram Govaerts, chief operating officer, deputy director general of research a.i. and director of the Integrated Development program at CIMMYT.

The project, called Aguas Firmes (Spanish for “Firm Waters”), also seeks to recharge two of Mexico’s most exploited aquifers, by restoring forests and building green infrastructure.

“Our priority is water, which is the basis of our business but, above all, the substance of life,” said Cassiano De Stefano, chair of Grupo Modelo, one of the Mexico’s leading beer companies. “We’ve decided to lead by example by investing considerably in restoring two aquifers that are essential to Zacatecas and Hidalgo’s development.”

The German development agency GIZ, one of CIMMYT’s top funders, is also investing in this alliance that will benefit 46,000 farmers in Hidalgo and 700,000 farmers in Zacatecas.

“We are very proud of this alliance for sustainable development that addresses a substantial problem in the region and strengthens our work on biodiversity conservation and sustainable use of natural resources in Mexico,” said Paulina Campos, Biodiversity director at GIZ Mexico.

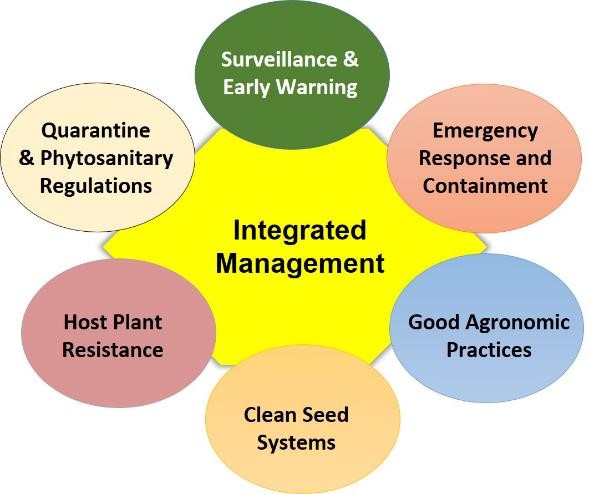

CIMMYT undertakes participatory agricultural research activities with local farmers to collaboratively develop and implement sustainable farming practices and technologies that help reduce water consumption in grain production by up to 30%.

INTERVIEW OPPORTUNITIES:

Bram Govaerts – Chief Operating Officer, Deputy Director General of Research a.i. and Director of the Integrated Development program, CIMMYT

FOR MORE INFORMATION, OR TO ARRANGE INTERVIEWS, CONTACT:

Ricardo Curiel, Senior Communications Specialist for Mexico, CIMMYT. r.curiel@cgiar.org, +52 (55) 5804 2004 ext. 1144

ABOUT CIMMYT:

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies. For more information, visit staging.cimmyt.org.