Women in agriculture mechanization in Bangladesh

Agriculture mechanization in Bangladesh connects local manufacturers of machinery parts (which is mainly done by the country’s light engineering industry) and the operation of those machines, generally run by machinery solution providers. These two workforces are equally male-dominated. The reasons behind this are social norms, and family and community preconceptions, coupled with the perception that women cannot handle heavy machinery. But a deeper look into this sector shows us a different reality, where many women are working enthusiastically as part of agriculture mechanization.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is supporting women to work in light engineering workshops, and to become entrepreneurs by providing machinery solutions to farmers.

Painting her own dream

Rokeya Begum, 39, has been working in Uttara Metal Industries for three and half years, clearing up and assisting her male colleagues in paint preparation. All this time, she wanted to be the one doing the painting.

Begum was one of the 30 young women from Bogura, Northern Bangladesh, recently trained by CIMMYT through the Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia-Mechanization Extension Activity (CSISA-MEA). They learnt various aspects of the painting trade and related operational techniques, such as mixing colors, the difference between primer and topcoats, and health and safety in the workplace.

Now the focus is on job creation for women in the sector. CIMMYT has initiated discussions with established enterprises to recruit women as painters in their workshops, with all the benefits of their male counterparts.

Having completed painting training, Begum practices spray painting for an hour every day. Her employer is happy with her finished work and plans to promote her to the position of painter. Begum says, “I’m so happy to have learned a new technique — plus I really enjoy the work.” Her current pay of $12 per week will increase by 50% when she starts her new job.

Alongside training, this mechanization activity is working to create a decent and safe working environment for women, including adequate, private and safe spaces, such as bathrooms and places to take breaks.

Seedling of an entrepreneur

For the first time ever, in the last monsoon aman rice cultivation season, Kulsum Akter, 30, earned $130, by selling rice seedlings she had grown to be planted out by mechanical rice transplanters. Two years ago, Akter’s husband Md. Abdul Motaleb bought a rice transplanter with the assistance of a government subsidy from the Government of Bangladesh’s Department of Agricultural Extension. While he invested $5,000 in the machine, his skills in operating it were sub-par.

Supported by the USAID-funded Feed the Future Bangladesh Mechanization and Extension Activity, Motaleb was trained in mechanized rice transplanter operation by a private company, The Metal Pvt. Ltd.

Akter was in turn trained in special techniques for growing seedlings so they can be planted out using a rice transplanting machine. CIMMYT then provided technical and business guidance to this husband-and-wife duo, enabling them to embark confidently on a strong business venture. Key training topics included growing mat-type seedlings for machines, business management, cost-benefit analysis, product promotion and business expansion concepts. Motaleb went on to provide mechanical transplanting services to other farmers in the locality.

Meanwhile, Akter was inspired to take the lead in preparing seedlings as a business venture to sell to farmers who use mechanical rice transplanters. Akter invested $100 in the last aman season, by the end of which she had earned $230 by selling the seedlings in just one month. This success has encouraged her to prepare seedlings for many more farmers during the winter rice production season. “The training in rice transplanter operation and seedling preparation was a gift for us. I’m trying to get more women into this business — and I’m pretty optimistic about it,” Akter says. Through the Mechanization and Extension Activity, CIMMYT aims to create more than 100 women entrepreneurs like Akter who will contribute to the mechanization of agriculture through their work as service providers.

CSISA-MEA’s work increases women’s capacity to work in the agricultural mechanization sector and manage machinery-based businesses through technical and business training. Through opportunities like these, more women like Begum and Akter will be enabled to achieve self-sufficiency and contribute to the development of this sector.

Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia Mechanization Extension Activity (CSISA-MEA) is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Feed the Future initiative.

Cover photo: The CSISA-MEA project increases women’s capacity to work in the agricultural mechanization sector, therefore achieving self-sufficiency. (Abdul Momin/CIMMYT)

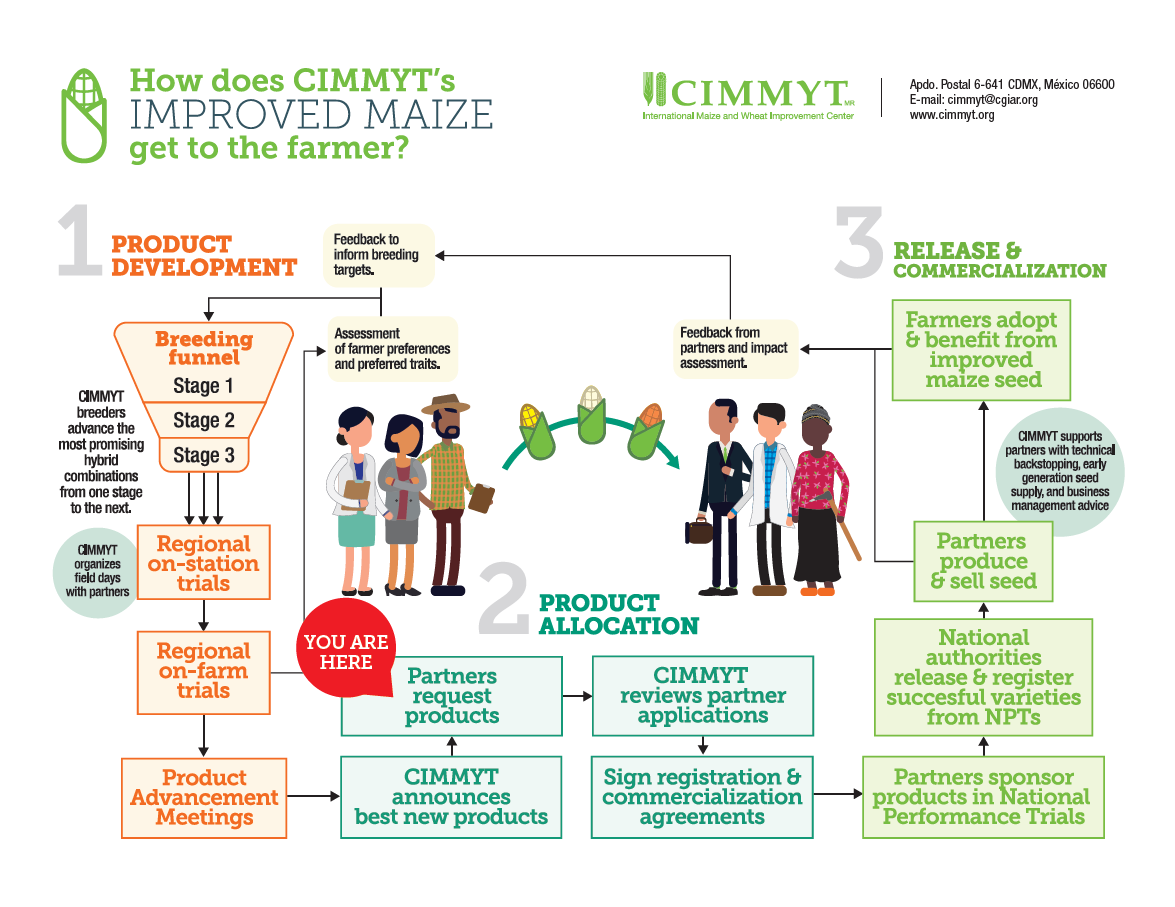

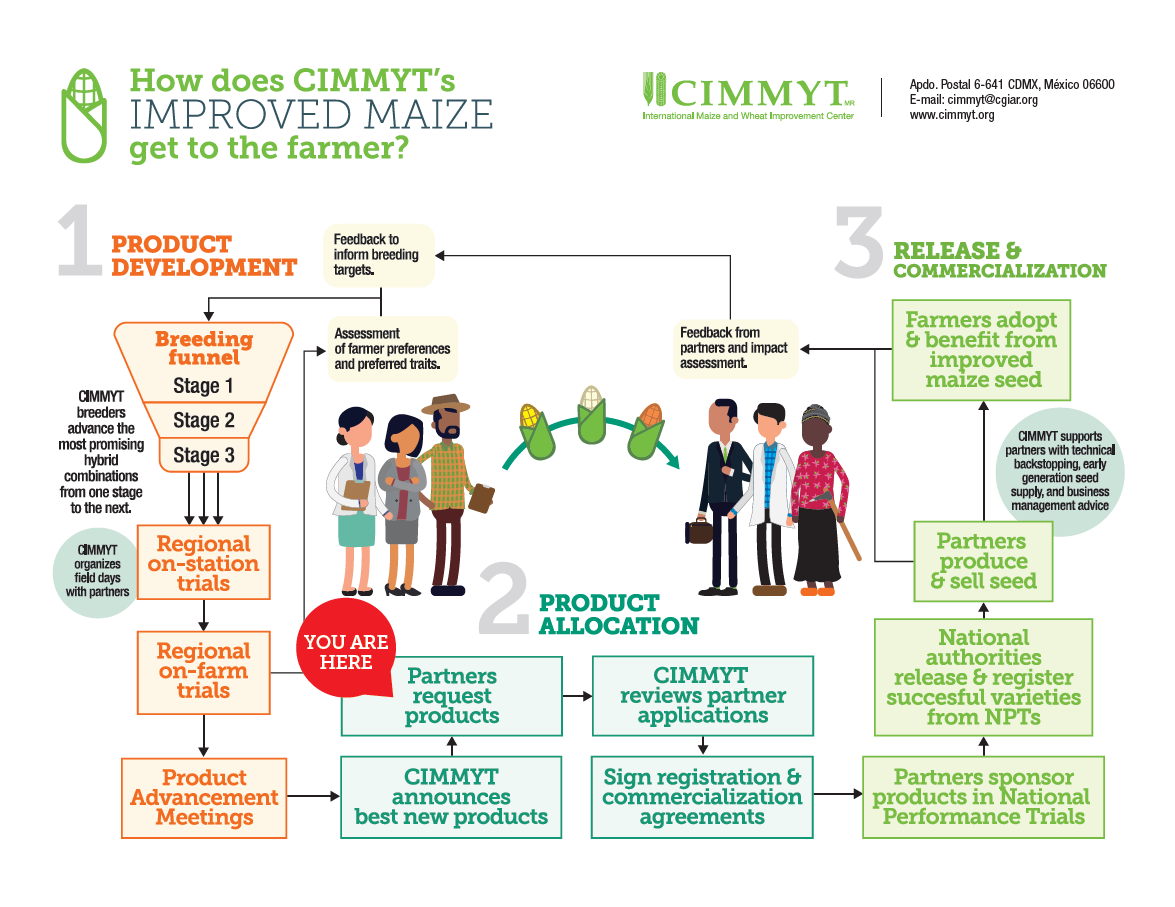

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is offering a new set of elite, improved maize hybrids to partners for commercialization in southern Africa and similar agro-ecological zones. National agricultural research systems (NARS) and seed companies are invited to apply for licenses to register and commercialize these new hybrids, in order to bring the benefits of the improved seed to farming communities.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is offering a new set of elite, improved maize hybrids to partners for commercialization in southern Africa and similar agro-ecological zones. National agricultural research systems (NARS) and seed companies are invited to apply for licenses to register and commercialize these new hybrids, in order to bring the benefits of the improved seed to farming communities.