People of the Clouds

CIMMYT E-News, vol 3 no. 9, September 2006

The Nepal Hill Maize Research Project, supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), reaches out to Nepal’s poorest farmers with new varieties and farming practices selected by the farmers themselves.

The Nepal Hill Maize Research Project, supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), reaches out to Nepal’s poorest farmers with new varieties and farming practices selected by the farmers themselves.

Coca Cola, arguably the world’s most ubiquitous commercial beverage, has not yet reached the villagers and farmers who live on top of the cloud-shrouded hills of eastern Nepal. That’s how remote they are. There is a road, but it is 600 meters below in the valley and the only way in and out of the village is via a precarious, rubble-strewn and sometimes terrifyingly steep foot-path. Everything must be carried up and down this track on people’s backs. Here the staple food for centuries has been maize but many farmers in the region cannot grow enough maize to last the year. Their needs have provided a focus for work in which CIMMYT, the Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC), SDC, and other partners, reach these “unreached” people.

One of them is Bishnu Maya. She is a single mother of three who farms 0.6 hectares of terraced land on the steep slopes. She is a very good farmer but it takes every penny she earns to make sure her children can go to school. “With education they can get jobs and have a better life,” she says. Bishnu Maya is a ‘dalit’; the poorest of the poor in Nepal, an untouchable often shunned by better-born villagers. Nevertheless, her tiny farm is a marvel. She grows maize, millet, tomatoes, and cucumbers on her land. She has a water buffalo, two cows, some chickens, and goats. A year ago electricity came to the village and now she has a small radio and a light bulb. What she has not had until now is enough maize to last the year. The traditional varieties have small ears, one per plant, and the maize plants themselves grow very tall and often fall down in the wind, not only reducing the maize yield but also damaging the intercropped plants below them.

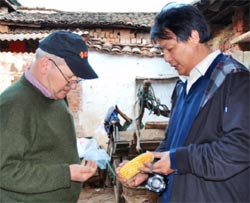

Maya agreed to help in participatory evaluations of maize varieties developed with material from CIMMYT and NARC that could overcome the main barriers to production on her land. She uses some of her land for a demonstration plot of the variety she has selected as the best replacement for her traditional maize. It is shorter with a sturdier stalk, has two large ears per plant and matures earlier than the maize she has been used to growing. On top of that the new variety stays green after the maize is mature, so it makes a better feed for her livestock.

The project has intentionally focused on women farmers and those who cannot produce enough food to feed their families, testing and promoting technologies that can be implemented by the farmers themselves. While the initial trials are conduced at the NARC research station at Pakhribas, an hour’s drive away once you reach the road in the valley, vital research work is conducted with farmers like Maya on their farms. In the past recommendations about varieties and agricultural practices were based on trials conducted exclusively at research stations, rarely taking into account the real world in which the hill farmers like Maya live and work. “Even on-farm research tended to try to create conditions on farms that matched the research stations, rather than finding solutions to existing farm problems,” says CIMMYT’s Memo Ortiz-Ferrara, who leads the project.

The new approach has helped farmers choose more appropriate varieties based on their own criteria from a “basket of choices” (5-10 varieties are offered in one season). It has also helped to expand areas growing new varieties on one hand, and improve crop management practices on the other. Depending on the location, farmers have observed 20-50% higher grain yield with the new varieties.

“Now I have enough and can sell some surplus to pay for my children’s education,” Bishnu says.

The second phase of the project is just coming to an end and an evaluation team has begun a series of in depth interviews with participating researchers and farmers to determine the overall impact.

Participatory research is a vital part of many CIMMYT projects around the world (see the companion story: CIMMYT researchers say participatory research supports their achievements).

For information contact Memo Ortiz-Ferrara (g.ortiz-ferrara@cgiar.org)

Farmer Juan Castillejos Castro of the village Dolores, Jaltenango, state of Chiapas, in southeastern Mexico, leaned forward in the humid, mid-morning heat and pondered the question: had household nutrition improved in the last 10 years? “From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, even I was malnourished to the point I couldn’t work,” he says. “Now things have gotten better, and the credits have helped a lot.”

Farmer Juan Castillejos Castro of the village Dolores, Jaltenango, state of Chiapas, in southeastern Mexico, leaned forward in the humid, mid-morning heat and pondered the question: had household nutrition improved in the last 10 years? “From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, even I was malnourished to the point I couldn’t work,” he says. “Now things have gotten better, and the credits have helped a lot.”

Remembering the life of Dr. Robert Havener, former Director General of CIMMYT.

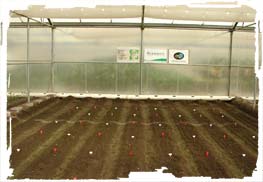

Remembering the life of Dr. Robert Havener, former Director General of CIMMYT. On 12 March 2004, CIMMYT took a modest but historic step in the development of drought tolerant wheat, when a small trial plot was sown to genetically modified (transgenic) wheat in a screenhouse at the Center’s headquarters in Texcoco, Mexico. This is the first time that transgenic wheat has been planted under field-like conditions in Mexico, and rigorous biosafety procedures are being followed.

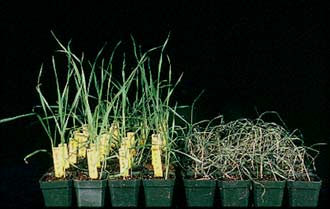

On 12 March 2004, CIMMYT took a modest but historic step in the development of drought tolerant wheat, when a small trial plot was sown to genetically modified (transgenic) wheat in a screenhouse at the Center’s headquarters in Texcoco, Mexico. This is the first time that transgenic wheat has been planted under field-like conditions in Mexico, and rigorous biosafety procedures are being followed.

In the war against drought each victory is very hard-fought. Stress tolerant maize will make a difference.

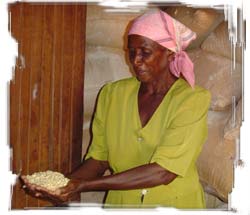

In the war against drought each victory is very hard-fought. Stress tolerant maize will make a difference. In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

Breeding knowledge combined with cutting-edge laboratory analysis will produce maize rich in vital nutrients.

Breeding knowledge combined with cutting-edge laboratory analysis will produce maize rich in vital nutrients.

Global Rust Initiative tackles a clearly present danger.

Global Rust Initiative tackles a clearly present danger.

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences  This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance.

This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance. CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.

CIMMYT maize helps villagers quadruple their yields.