Saving Mexican maize farmers’ soil

CIMMYT E-News, vol 4 no. 10, October 2007

Resource-conserving practices introduced by a CIMMYT project are taking root among farmers in the central Mexican Highlands.

In the fields above the community of San Felipe del Progreso, in the central Mexican Highlands, smallholder farmers grow maize year after year in conventionally-plowed fields. Feliciano Cruz says his neighbors think he’s crazy for trying new resource-conserving practices and other crops, but nonetheless many are interested. While he’s showing a group of visiting researchers his fields, a neighboring farmer comes along and asks if Cruz can help him to try the new system. “I want to get involved,” he explains. “My fields are getting too dry, and when that happens the soil becomes really hard.” Cruz enthusiastically explains the benefits of keeping crop residues on the soil to stop it drying out. “We’re learning step by step,” he says. It seems that farmers here are willing to take a risk on something unorthodox.

“There are two major challenges for farmers in this area: soil erosion and labor shortages,” says Bram Govaerts, CIMMYT postdoctoral fellow in crop systems management, “and we think conservation agriculture will help with both.” The region’s volcanic soils are fertile but relatively thin, and when dry and exposed are easily washed away by the heavy, irregular rains, leaving behind rocky, infertile material. This process is clearly visible in the landscape’s scanty topsoils and eroded gullies, and all too apparent to farmers. Few farmers here are able to harvest surpluses to sell, and most rely on supplementary sources of income. Meanwhile, most of the region’s young men leave to seek work in the USA, and many fields lie fallow.

In the new system, introduced by a collaborative project between CIMMYT and local institutions involving local farmers, maize is sown directly into permanent raised beds, and the stalks and leaves, or “residues” of the crop are retained on the fields. These innovations protect the structure of the soil, retain soil moisture, and prevent erosion. Direct seeding is also less labor-intensive; conventional tillage requires several plowings and harrowings, whereas fields with permanent beds require only a single surface pass each year to reshape the beds. CIMMYT has also introduced new crops for farmers to try in rotation with maize.

The project is based on CIMMYT science and involves a number of Mexican partners: ICAMEX, the agricultural research institute for the state of Mexico (providing funding and receiving training), Mexico’s Research and Advanced Studies Center (Cinvestav), and the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico (UAEM), with funding from the Flemish Interuniversity Council – University Development Cooperation (VLIR-UDC). CIMMYT has several long-term conservation agriculture trial plots on its research stations in Mexico. These provide valuable scientific data about management practices, but they are also being used for training and capacity building. The project began with a field day at the Toluca station, where Fernando Delgado, station manager and local conservation agriculture champion, demonstrated resource-conserving practices to farmers from partner communities. CIMMYT is now working to test these in farmers’ fields. “This is a mutual learning process,” says Govaerts. “We’re trying to extend the technology to farmers’ fields; at the same time we are developing on-farm research modules and we’re bringing back what we learn—both from successes and failures.” Next year will be the project’s third planting year, and Govaerts anticipates real success, with good crops under the new system.

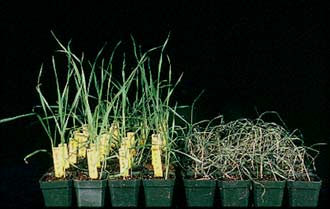

The two systems are being tested side by side: on one half of his test plot Olegario Gonzalez has planted conventionally-tilled maize (foreground), on the other he is growing a wheat crop in rotation with maize using resource-conserving practices.Farmers see the benefits of the system and are as determined as the scientists to stick with it, even where things haven’t gone according to plan. For example, the residues of the first year’s maize crop were left on the fields, but other locals took it for fuel and fodder. In Cruz’s test maize field, this meant that in the second year the soil was too dry for zero-tillage planting (which is shallower than conventional planting) and the maize crop failed. However, in a few places where the residues remained the seedlings grew well, convincing Cruz and other participating farmers that residue retention could work. They themselves decided to replant the field with maize, even though it was too late in the season to yield any grain, just to grow plenty of biomass to retain as residues for the following year. The project will assist the farmers to fence their plots to protect this year’s residues.

“I will definitely continue with the new system,” says Cruz, who is in no doubt as to its advantages. “Firstly, it is less work. There is no plowing or harrowing, which saves a lot on costs. Secondly, it conserves the soil—water filters in and doesn’t run off. Finally, the maize doesn’t fall over as much, as it grows less and the roots go deeper.”

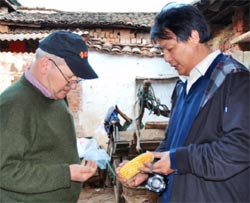

Olegario Gonzalez (second from right) discusses his wheat crop; his neighbors are already asking to buy his grain.

Cruz is also enthusiastic about the alternative crops that project members planted with the farmers. “It’s important that we have the option to try new things,” he says. “The land gets tired if we just plant maize, maize, maize.” Oats and triticale are his favorites so far, growing well enough to be used for fodder and still leave good residues. In the neighboring community of San Pablo, farmer Olegario Gonzalez is growing wheat, and he has found that there is a local demand. “My neighbors are already asking to buy my wheat to add to tortillas [the staple Mexican flatbread] and for seed,” he says, indicating the rows of ripening grain.

“Now that we’ve seen that farmers like the system, the next stage is to scale it up,” says Govaerts. “Farmers need zero-tillage machinery suitable for small tractors, so we’re working with companies to commercialize a multi-use, multi-crop machine. We’ll also be helping farmers to find and develop local markets.” The project is currently working with a few farmers who are respected in their communities, and next year plans to invite more farmers to the test plots to see and learn about the system in action.

CIMMYT has been involved in testing conservation agriculture and testing it with farmers all over the world. This project is one of several throughout Mexico developed together with local partners. Govaerts hopes that CIMMYT’s long-term trial plots will act as hubs for farmer visits, sowing the seeds for resource conservation in many more local communities.

For more information: Bram Govaerts, postdoctoral fellow, crop systems management (b.govaerts@cgiar.org)

Solving a major disease problem in durum wheat was not enough to satisfy farmers. They need and will get quality too.

Solving a major disease problem in durum wheat was not enough to satisfy farmers. They need and will get quality too.

The Nepal Hill Maize Research Project, supported by the

The Nepal Hill Maize Research Project, supported by the

Farmer Juan Castillejos Castro of the village Dolores, Jaltenango, state of Chiapas, in southeastern Mexico, leaned forward in the humid, mid-morning heat and pondered the question: had household nutrition improved in the last 10 years? “From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, even I was malnourished to the point I couldn’t work,” he says. “Now things have gotten better, and the credits have helped a lot.”

Farmer Juan Castillejos Castro of the village Dolores, Jaltenango, state of Chiapas, in southeastern Mexico, leaned forward in the humid, mid-morning heat and pondered the question: had household nutrition improved in the last 10 years? “From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, even I was malnourished to the point I couldn’t work,” he says. “Now things have gotten better, and the credits have helped a lot.”

Remembering the life of Dr. Robert Havener, former Director General of CIMMYT.

Remembering the life of Dr. Robert Havener, former Director General of CIMMYT. On 12 March 2004, CIMMYT took a modest but historic step in the development of drought tolerant wheat, when a small trial plot was sown to genetically modified (transgenic) wheat in a screenhouse at the Center’s headquarters in Texcoco, Mexico. This is the first time that transgenic wheat has been planted under field-like conditions in Mexico, and rigorous biosafety procedures are being followed.

On 12 March 2004, CIMMYT took a modest but historic step in the development of drought tolerant wheat, when a small trial plot was sown to genetically modified (transgenic) wheat in a screenhouse at the Center’s headquarters in Texcoco, Mexico. This is the first time that transgenic wheat has been planted under field-like conditions in Mexico, and rigorous biosafety procedures are being followed.

Keepers of worldwide maize germplasm collections meet at CIMMYT to see how they can work together to protect and conserve these resources.

Keepers of worldwide maize germplasm collections meet at CIMMYT to see how they can work together to protect and conserve these resources.

In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

In the 2006-07 cropping season, 82 registered maize seed companies produced the bulk of just over 100,000 tons of improved maize seed that were marketed in the major maize producing countries of eastern and southern Africa (excluding South Africa) — enough to sow 35% of the maize land in those countries.

Breeding knowledge combined with cutting-edge laboratory analysis will produce maize rich in vital nutrients.

Breeding knowledge combined with cutting-edge laboratory analysis will produce maize rich in vital nutrients.

Global Rust Initiative tackles a clearly present danger.

Global Rust Initiative tackles a clearly present danger.

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences

In March, CIMMYT scientists continued their pursuit of drought tolerant wheat with the second field trial of transgenic lines carrying the DREB gene, given to CIMMYT by Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences  This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance.

This second trial narrows the focus of investigation to four transgenic lines and uses a larger plot to ensure better control and analysis. It will also expose the experimental lines and control plants to both watered and drought conditions to determine their respective performance.