Women driving changes in agriculture

Marianne Bänziger is the Deputy Director General for Research and Partnerships for CIMMYT.

Marianne started her career with CIMMYT as a post-doctoral fellow in 1994 working in Maize Physiology to develop varieties tolerant to low soil fertility and drought. She was based at the CIMMYT office in Zimbabwe during 1996-2004, after which she was appointed Director of the Maize Program, based in Nairobi. In 2009 Marianne became the DDG-Research. In that capacity, she led the development of the CGIAR research programs for maize and wheat.

Marianne started her career with CIMMYT as a post-doctoral fellow in 1994 working in Maize Physiology to develop varieties tolerant to low soil fertility and drought. She was based at the CIMMYT office in Zimbabwe during 1996-2004, after which she was appointed Director of the Maize Program, based in Nairobi. In 2009 Marianne became the DDG-Research. In that capacity, she led the development of the CGIAR research programs for maize and wheat.

Why did you choose agriculture?

I chose agriculture because it’s a science that impacts people’s lives. It’s as simple as that. I was also attracted to that it builds up on a wide range of disciplines – biology, chemistry, math, socioeconomics.

Your maize breeding work in Eastern and Southern Africa had, and still has, an enormous impact. Do you think that as a woman you gave a specific gender perspective to your research?

I lived in Africa for almost 15 years and it was impossible to ignore the people — the families — who struggled to improve their livelihoods. I saw them every day. We interacted frequently with both men and women farmers. In the environments we worked, the concern of the women farmers was more on avenues that improved household food security while the men were more concerned about selling their crops and generating income. Of course, families need both: Enough food to eat and income to pay for education fees, health costs, and things like farm inputs.

Another very obvious learning was that Africa has many strong women who drive change across the continent. You find them among farmers, among professionals, and among researchers alike.

Did you work differently as a woman breeder?

There have been books written about differences in men and women “behavior” or “traits” – In my opinion, these are stereotypes and they often break down. Every person puts their imprint, their personality, on their work, for better or worse, whether with “male” and “female” stereo-typed traits.

Did you have rural women in mind when you were developing different varieties of maize?

Interacting with farmers in Africa, I tried to understand how they make decisions and how those decisions link with and meet up with real options in the value chain. For instance, there was a stronger preference for hybrids by male farmers while female farmers preferred OPVs (open-pollinated varieties, which allow farmers to save seeds). We created an integrated breeding program that offered both OPVs and hybrids. The first generation of successful products was OPVs, “women typed” products. However, the reason for them to become available early on had to do with the seed sector ability to scale them up more rapidly as compared drought tolerant hybrids, not whether they were “female” or “male” preferred. The lesson learned is that researchers can craft gender differentiated options, we however need to understand the value chain to ensure that those options indeed become available and accessible at farm level.

Why did women prefer OPVs?

It gave them a greater sense of security about their ability to feed their families. Because they could save seed from year-to-year they felt more in control of their lives. Men preferred hybrids because they had a higher yield which meant more money in the market.

Unfortunately, preferences too often get treated as an either/or issue. We involved schools in rural areas in executing on-farm trials. I remember one particular instance talking to the headmaster of a school located in a drought prone area. I learned that classes had only one schoolbook which they had to share and pass around more than 50 children. Except for two old benches everybody was sitting on the floor. I asked him if the children – under these circumstances – were able to get a quality education and go to secondary school later on. He said the greatest concern wasn’t the lack of benches or books but that the children came to school and fell asleep because they were hungry. They were hungry because they only got one meal a day.

That school was in a drought-prone area and it made me once again realize how real and prominent food insecurity was. So, if you are a mother in such an environment, clearly the first thing you are concerned about is feeding your family and have a sense of control that you can achieve that. Setting food security as a priority does not mean that the woman would not want to grow hybrids as her family becomes more food secure. She also wants income for books and school fees. She would like to see her children learning a profession and likely leave agriculture. We must understand that poverty and hunger are intertwined and do our best to address both.

What do you think are the priorities to empower rural women in regions where we work?

Last week, I was in India at a meeting with farmers – both men and women – and one of the women stood up and said, “We want to have the same access to information and opportunities as men have.”

In the past, women have been deprived of information, of access to credit, and of the same opportunities offered to men. Fortunately many organizations including governmental organization begin to put more proactive gender strategies in place. We can and must ensure that more women get access to empowering information and opportunities. In our case, we are right now engaging in a gender audit of our projects, looking for new avenues to empower women. This is not just about analyzing how women or men think, but asking ourselves how we can empower women through our interventions. We however also have to accept that certain, indeed many, interventions have benefits to men and women alike. So doing a gender audit isn’t about being able to tick off the box and say ‘we addressed the gender aspects of this project’. It is about enriching our understanding how interventions, people, society, value chains, opportunities connect and then choosing more effective interventions that improve the livelihoods of the poor.

What advice would you give to young women scientists?

Pursue your dreams and be what you would like to be. I’d offer that advice to everyone, independent of whether they are a woman or a man, tall or short, or one nationality or the other.

Emma Gaalaas Mullaney is a researcher studying gender and agriculture. She has served as a Youth Representative to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and Commission on the Status of Women since 2010.

Emma Gaalaas Mullaney is a researcher studying gender and agriculture. She has served as a Youth Representative to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity and Commission on the Status of Women since 2010. Nicole Mason is an assistant professor of International Development at the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics at Michigan State University.

Nicole Mason is an assistant professor of International Development at the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics at Michigan State University. A recently-emerged disease in Eastern Africa, maize lethal necrosis (

A recently-emerged disease in Eastern Africa, maize lethal necrosis ( A February 2013 report from

A February 2013 report from

During 4-8 February 2013, stakeholders of the Water Efficient Maize for Africa (

During 4-8 February 2013, stakeholders of the Water Efficient Maize for Africa ( On 6 February 2013, the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (

On 6 February 2013, the Borlaug Institute for South Asia (

In Timor-Leste, maize is the main staple crop grown by 88% of farming households. However, availability of quality seed of improved maize varieties is a major bottleneck for enhancing crop production and productivity. Experiences gained through the

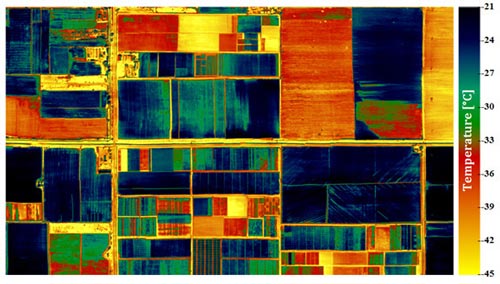

In Timor-Leste, maize is the main staple crop grown by 88% of farming households. However, availability of quality seed of improved maize varieties is a major bottleneck for enhancing crop production and productivity. Experiences gained through the  In rural areas surrounding Chipata in eastern Zambia, tobacco, cotton, and maize seem to dominate the agricultural landscape. If you look closer, you will also see smaller fields with groundnuts, cowpeas, soybeans, and sunflowers. But there is yet another dimension of diversity: the different growth stages and (inadequate) fertilization levels of the crops have resulted in a patchwork of yellow to deep green fields of many sizes and shapes, with various degrees of weed infestation. In this smallholder farming area with an average annual rainfall of more than 1,000 mm, it is neither easy to stay ahead of the weeds on all fields, nor to buy enough fertilizer for a healthy crop.

In rural areas surrounding Chipata in eastern Zambia, tobacco, cotton, and maize seem to dominate the agricultural landscape. If you look closer, you will also see smaller fields with groundnuts, cowpeas, soybeans, and sunflowers. But there is yet another dimension of diversity: the different growth stages and (inadequate) fertilization levels of the crops have resulted in a patchwork of yellow to deep green fields of many sizes and shapes, with various degrees of weed infestation. In this smallholder farming area with an average annual rainfall of more than 1,000 mm, it is neither easy to stay ahead of the weeds on all fields, nor to buy enough fertilizer for a healthy crop. To discuss possible expansion of

To discuss possible expansion of  While maize is an important cereal crop in Bangladesh – third only to rice and wheat in terms of cultivated area and second to rice in terms of production – it has not been widely used for human consumption. To discuss filling this gap, CIMMYT-Bangladesh and Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (

While maize is an important cereal crop in Bangladesh – third only to rice and wheat in terms of cultivated area and second to rice in terms of production – it has not been widely used for human consumption. To discuss filling this gap, CIMMYT-Bangladesh and Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute ( On 13 February 2013, CIMMYT inaugurated a new US$ 25 million research complex at its headquarters in El Batán. The new advanced bioscience research facilities, 45 kilometers (20 miles) from Mexico City, marked its grand opening to a crowd of more than 100 invited guests.

On 13 February 2013, CIMMYT inaugurated a new US$ 25 million research complex at its headquarters in El Batán. The new advanced bioscience research facilities, 45 kilometers (20 miles) from Mexico City, marked its grand opening to a crowd of more than 100 invited guests.