Are cows the next development boom for smallholder farmers?

HARARE, Zimbabwe- Smallholder livestock farmers in Zimbabwe are beginning to flip every notion about the country’s industry on its head.

Dairy and beef livestock production play an important economic and nutritional role in the lives of many Zimbabwean farm households. However, rearing livestock has traditionally been expensive as livestock take a lot of space and suck up a lot of money for feed and maintenance, leaving poor farmers to rarely see a significant return on investment in these animals, let alone compete with larger livestock producers in the country.

Dairy and beef livestock production play an important economic and nutritional role in the lives of many Zimbabwean farm households. However, rearing livestock has traditionally been expensive as livestock take a lot of space and suck up a lot of money for feed and maintenance, leaving poor farmers to rarely see a significant return on investment in these animals, let alone compete with larger livestock producers in the country.

Zimbabwe’s small-scale livestock producers face a wide range of challenges but key among these is the lack of adequate supplementary feed, particularly during the dry winter months when natural grazing pastures are dry. As a result, productivity of the animals is often very poor, and livestock producers miss out on the prospects of increasing their incomes from beef and dairy cattle production.

In addition, increasing human populations associated with expansion in arable land area continues to put pressure on pastures which continue to dwindle in both quality and area leading to insufficient grazing to sustain livestock throughout the year. Because of this and a decreasing natural resource base, farming systems are under greater pressure to provide sufficient food and to sustain farmers’ livelihoods.

In Zimbabwe’s sub-humid Mashonaland East Province, groups of innovative farmers, extension workers and experts in crop-livestock integration are making livestock sustainable and lucrative for more than 5,000 farmers who are now beginning to increase their profits – for some up to 70 percent – thanks to new efforts led by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in collaboration with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and other partners. This initiative seeks to integrate crops and livestock technologies with a major focus on food, feed and soil.

Together, this consortium is working with the smallholder farmers to introduce forage legumes such as mucuna and lablab using conservation agriculture-based sustainable intensification practices.

With this approach, maize productivity for food security is improved through forage and pulse legume rotations under conservation agriculture while livestock benefit from feeding on increased biomass output and conserved supplementary feed prepared from the forage legumes.

Maintaining the availability of adequate feed for livestock is crucial to rural smallholders in Zimbabwe. Most smallholders could not afford to buy commercial supplements for their natural pastures, especially during the long dry winter season when livestock usually run short of feed. Also, they did not know how to produce cost-effective home-grown feeds. Thanks to this agribusiness, the farmers learned to improve on-farm fodder production.

Conservation agriculture is a cropping system based on the principles of reduced tillage, keeping crop residues retention on the soil surface, and diversification through rotation or intercropping maize with other crops. The immediate benefits of conservation agriculture are: labor and cost savings, improved soil structure and fertility, increased infiltration and water retention, less erosion and water run-off–thus contributing to adaptation to the negative effects of climate variability and change. Through improved management and use of conservation agriculture techniques maize yields were increased from the local average of 0.8 tons per hectare to over 2.5 tons per hectare depending on rainfall and initial soil fertility status.

Mucuna (also known as velvet bean), is well-adapted to the weather conditions in Zimbabwe and can grow with an annual rainfall of 300 mm over four to six months. Growing this cover crop is an agroecological practice that helps farmers address many problems such as poor access to inputs, soil erosion and vulnerability to climate change.

In addition, mucuna’s high biomass yield also smothers weeds so farmers do not have to spend time weeding. Mucuna also improves soil by fixing up to 170 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare and producing up to 200 kilograms of nitrogen from its residues. Moreover, the biomass produced effectively controls wind and water erosion.

Under the conservation agriculture systems employed here, cattle are used for reduced tillage using an animal drawn direct seeder or rippers in the cereal-legume production systems. Cattle manure is also used for fertilization. In turn, cattle benefit from the system through fattening on home formulated mucuna-based diets and feeding on crop residues.

Since 2012, smallholder farmers have received training and technical assistance on improved agricultural and animal husbandry practices for animal breeding, animal health and nutrition, fodder production and herd management. For example, farmers have learned to prepare nutritious feed rations for their livestock using locally available resources such as molasses and maize residues. As a result of these newly acquired skills, farmers have been better able to adapt to the severe drought currently affecting much of southern Africa.

As part of strengthening the project’s multi-stakeholder platform, a workshop was recently held at CIMMYT’s southern Africa regional office in Harare, Zimbabwe. The meeting brought together 40 participants including farmers and personnel from non-governmental organizations, the government and the private sector. The workshop sought to further enhance crop-livestock integration through facilitating agribusiness deals between the private sector and farmers. Farmers clinched a contract farming agribusiness deal with Capstone Seed Company to supply lablab seed. This means farmers have a guaranteed market for their lablab seed.

Makera Cattle Company also offered opportunities to farmers to improve their cattle breeds through crossing their local breeds with pedigree bulls. They agreed to supply bulls as breeding stock to interested farmers on a loan scheme.

Thanks to the spread of the crop-livestock project, Zimbabwean farmers are now able to engage in new market opportunities and improve their incomes by increasing crop and livestock productivity at a sustainable, affordable rate.

By focusing on a commercial approach, the project is ensuring long-term sustainability of the dramatic income increases and other benefits that the farmers have already witnessed. Helping farmers improve their productivity and living standards is an important first step, but the project also has to make sure the farmers have access to reliable markets.

CIMMYT’s Integrating Crops and Livestock for Improved Food Security and Livelihoods in Rural Zimbabwe (ZimCLIFs) project is working with more than 5,000 smallholder farmers to introduce fodder production. ZimCLIFs is funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) and implemented by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) as the lead agency, in collaboration with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Ecosystem Sciences, the University of Queensland, the Community Technology Development Organization (CTDO), the Cluster Agricultural Development Services (CADS) and the government of Zimbabwe. It seeks to strengthen potential synergies offered by crop-livestock integrated farming systems.

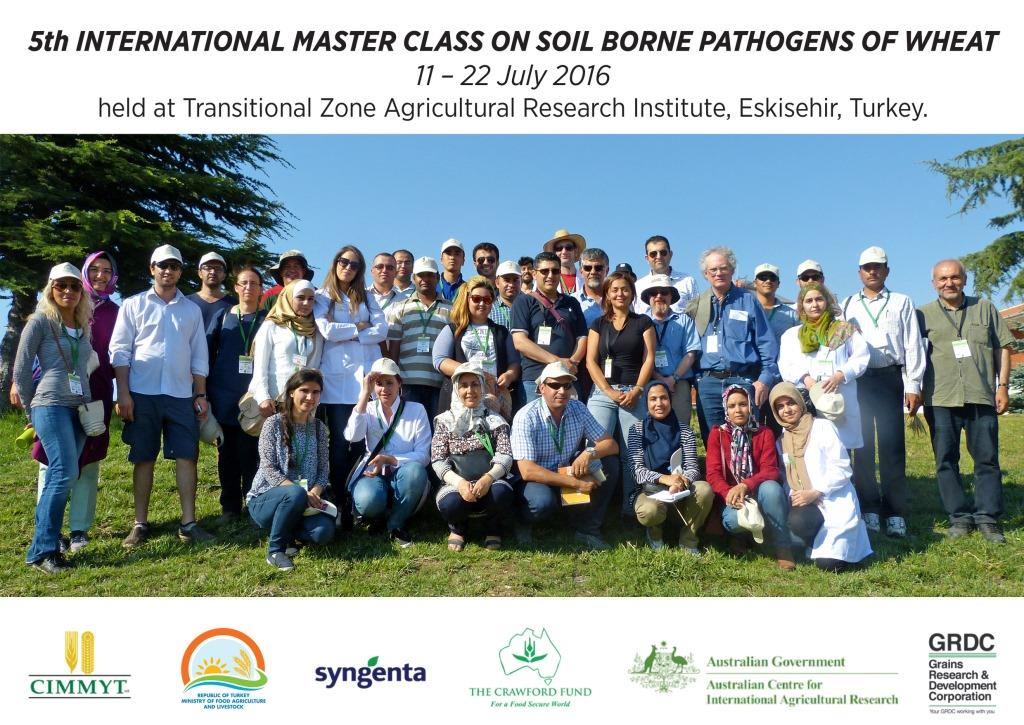

ESKISEHIR, Turkey — The 5th International Master Class on Soil Borne Pathogens of Wheat held at the Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute (TZARI), Eskisehir, Turkey, on 11-23 July 2016, brought together 45 participants from 16 countries of Central and West Asia and North Africa.

ESKISEHIR, Turkey — The 5th International Master Class on Soil Borne Pathogens of Wheat held at the Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute (TZARI), Eskisehir, Turkey, on 11-23 July 2016, brought together 45 participants from 16 countries of Central and West Asia and North Africa.