Bending gender norms: women’s engagement in agriculture

Researchers at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) have studied and witnessed that women, particularly in South Asia, have strongly ingrained and culturally determined gender roles.

While women play a critical part in agriculture, their contributions are oftentimes neglected and underappreciated. Is there any way to stop this?

On International Day of Women and Girls in Science, we spoke to Pragya Timsina about how women’s participation in agriculture is evolving across the Eastern Gangetic Plains and her findings which will be included in a paper coming out later this year: ‘Necessity as a driver of bending agricultural gender norms in South Asia’. Pragya is a Social Researcher at CIMMYT, based in New Delhi, India. She has worked extensively across different regions in India and is currently involved in various projects in India, Nepal and Bangladesh.

What is the current scenario in the Eastern Gangetic Plains of South Asia on gender disparities and women’s involvement in agriculture? Is it the same in all locations that your research covered?

Currently, traditional roles, limited mobility, societal criticism for violating gender norms, laborious unmechanized agricultural labor, and unacknowledged gender roles are among the social and cultural constraints that women face in the Eastern Gangetic Plains. Our research shows that while these norms exist throughout the Eastern Gangetic Plains, there are outliers, and an emerging narrative that is likely to lead to further bending (but not breaking, yet) of such norms.

Are there any factors that limit women from participating in agriculture?

Cultural and religious norms have influence gender roles differently in different households but there are definitely some common societal trends. Traditionally, women are encouraged to take on roles such as household chores, childcare, and livestock rearing, but our research in the Eastern Gangetic Plains found that in specific regions such as Cooch Behar (West Bengal), women were more actively involved in agriculture and even participated in women-led village level farmers’ groups.

How or what can help increase women’s exposure to agricultural activities?

At the community level, causes of change in gender norms include the lack of available labor due to outmigration, the necessity to participate in agriculture due to a labor shortage, and a greater understanding and exposure to others who are not constrained by gendered norms. There are instances where women farmers are provided access and exposure to contemporary and enhanced technology advances, information, and entrepreneurial skills that may help them become knowledgeable and acknowledged agricultural decision makers. In this way, research projects can play an important role in bending these strongly ingrained gendered norms and foster change.

In a context where several programs are being introduced to empower women in agriculture, why do you think they haven’t helped reduce gender inequality?

Our study reveals that gender norms that already exist require more than project assistance to transform.

While some women in the Eastern Gangetic Plains have expanded their engagement in public places as they move away from unpaid or unrecognized labor, this has not always mirrored shifts in their private spaces in terms of decision-making authority, which is still primarily controlled by men.

Although, various trends are likely to exacerbate this process of change, such as a continued shortage of available labor and changing household circumstances due to male outmigration, supportive family environments, and peer support.

What lessons can policymakers and other stakeholders take away to help initiate gender equality in agriculture?

Although gender norms are changing, I believe they have yet to infiltrate at a communal and social level. This demonstrates that the bending of culturally established and interwoven systemic gender norms across the Eastern Gangetic Plains are still in the early stages of development. To foster more equitable agricultural growth, policymakers should focus on providing inclusive exposure opportunities for all community members, regardless of their standing in the household or society.

What future do the women in agriculture perceive?

Increasing development projects are currently being targeted towards women. In certain circumstances, project interventions have initiated a shift in community attitudes toward women’s participation. There has been an upsurge in women’s expectations, including a desire to be viewed as equal to men and to participate actively in agriculture. These patterns of women defying gender norms appear to be on the rise.

What is your take on women’s participation in agriculture, to enhance the desire to be involved in agriculture?

Higher outmigration, agricultural labor shortages, and increased shared responsibilities, in my opinion, are likely to expand rural South Asian women’s participation in agricultural operations but these are yet to be explored in the Eastern Gangetic Plains. However, appropriate policies and initiatives must be implemented to ensure continued and active participation of women in agriculture. When executing any development projects, especially in the Eastern Gangetic Plains, policies and interventions must be inclusive, participatory, and take into account systemic societal norms that tend to heavily impact women’s position in the society.

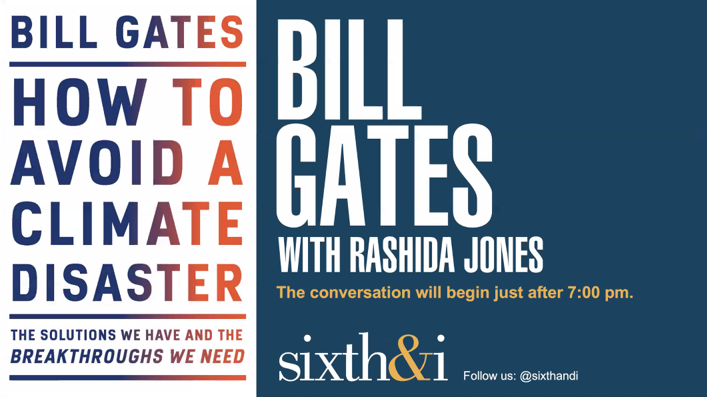

Global thought leader, philanthropist and one of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and CGIAR’s most vocal and generous supporters, Bill Gates, wrote a book about climate change and is now taking it around the world on a virtual book tour to share a message of urgency and hope.

Global thought leader, philanthropist and one of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and CGIAR’s most vocal and generous supporters, Bill Gates, wrote a book about climate change and is now taking it around the world on a virtual book tour to share a message of urgency and hope.