What is conservation agriculture?

If not practiced sustainably, agriculture can have a toll on the environment, produce greenhouse gases and contribute to climate change. However, sustainable farming methods can do the opposite — increase resilience to climate change, protect biodiversity and sustainably use natural resources.

One of these methods is conservation agriculture.

Conservation agriculture conserves natural resources, biodiversity and labor. It increases available soil water, reduces heat and drought stress, and builds up soil health in the longer term.

What are the principles of conservation agriculture?

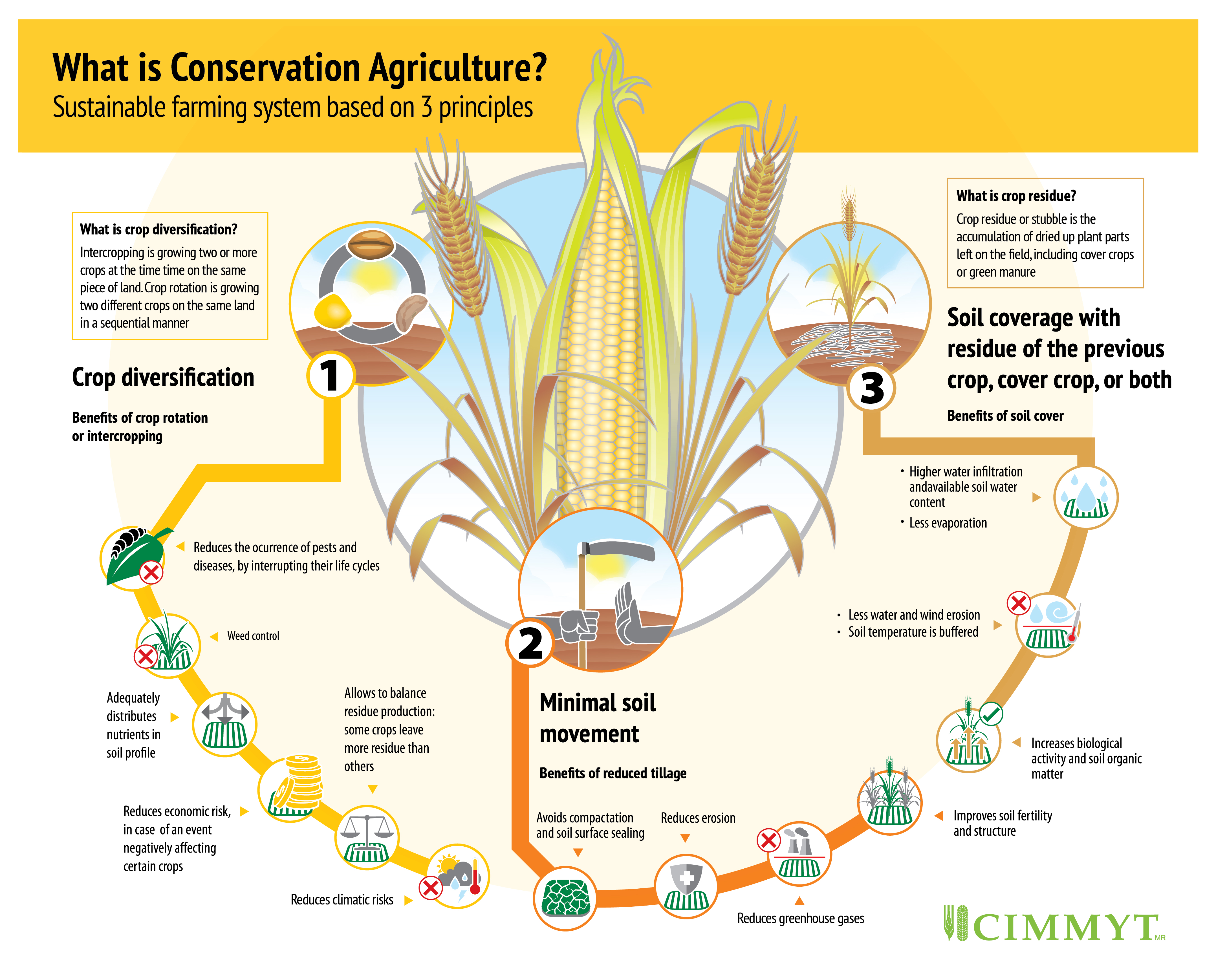

Conservation agriculture is based on the interrelated principles of minimal mechanical soil disturbance, permanent soil cover with living or dead plant material, and crop diversification through rotation or intercropping. It helps farmers to maintain and boost yields and increase profits, while reversing land degradation, protecting the environment and responding to growing challenges of climate change.

To reduce soil disturbance, farmers practice zero-tillage farming, which allows direct planting without plowing or preparing the soil. The farmer seeds directly through surface residues of the previous crop.

Zero tillage is combined with intercropping and crop rotation, which means either growing two or more crops at the same time on the same piece of land, or growing two different crops on the same land in a sequential manner. These are also core principles of sustainable intensification.

How is conservation agriculture different from sustainable intensification?

How is conservation agriculture different from sustainable intensification?

Sustainable intensification is a process to increase agriculture yields without adverse impacts on the environment, taking the whole ecosystem into consideration. It aims for the same goals as conservation agriculture.

Conservation agriculture practices lead to or enable sustainable intensification.

What are the benefits and challenges of conservation agriculture?

Zero-tillage farming with residue cover saves irrigation water, gradually increases soil organic matter and suppresses weeds, as well as reduces costs of machinery, fuel and time associated with tilling. Leaving the soil undisturbed increases water infiltration, holds soil moisture and helps to prevent topsoil erosion. Conservation agriculture enhances water intake that allows for more stable yields in the midst of weather extremes exacerbated by climate change.

While conservation agriculture provides many benefits for farmers and the environment, farmers can face constraints to adopt these practices. Wetlands or soils with poor drainage can make adoption challenging. When crop residues are limited, farmers tend to use them for fodder first, so there might not be enough residues for the soil cover. To initiate conservation agriculture, appropriate seeders are necessary, and these may not be available or affordable to all farmers. Conservation agriculture is also knowledge intensive and not all farmers may have access to the knowledge and training required on how to practice conservation agriculture. Finally, conservation agriculture increases yields over time but farmers may not see yield benefits immediately.

However, innovations, adapted research and new technologies are helping farmers to overcome these challenges and facilitate the adoption of conservation agriculture.

How did conservation agriculture originate?

The term “conservation agriculture” was coined in the 1990s, but the idea to minimize soil disturbance has its origins in the 1930s, during the Dust Bowl in the United States of America.

CIMMYT pioneered no-till training programs and trials in the 1970s, in maize and wheat systems in Latin America. In the 1980s this technique was also used in agronomy projects in South Asia.

CIMMYT began work with conservation agriculture in Latin America and South Asia in the 1990s and in Africa in the early 2000s. Today, these efforts have been scaled up and conservation agriculture principles have been incorporated into projects such as CSISA, FACASI, MasAgro, SIMLESA, and SRFSI.

Farmers worldwide are increasingly adopting conservation agriculture. In the 2015/16 season, conservation agriculture was practiced on about 180 mega hectares of cropland globally, about 12.5% of the total global cropland — 69% more than in the 2008/2009 season.

Is conservation agriculture organic?

Conservation agriculture and organic farming both maintain a balance between agriculture and resources, use crop rotation, and protect the soil’s organic matter. However, the main difference between these two types of farming is that organic farmers use a plow or soil tillage, while farmers who practice conservation agriculture use natural principles and do not till the soil. Organic farmers apply tillage to remove weeds without using inorganic fertilizers.

Conservation agriculture farmers, on the other hand, use a permanent soil cover and plant seeds through this layer. They may initially use inorganic fertilizers to manage weeds, especially in soils with low fertility. Over time, the use of agrichemicals may be reduced or slowly phased out.

How does conservation agriculture differ from climate-smart agriculture?

While conservation agriculture and climate-smart agriculture are similar, their purposes are different. Conservation agriculture aims to sustainably intensify smallholder farming systems and have a positive effect on the environment using natural processes. It helps farmers to adapt to and increase profits in spite of climate risks.

Climate-smart agriculture aims to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change by sequestering soil carbon and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and finally increase productivity and profitability of farming systems to ensure farmers’ livelihoods and food security in a changing climate. Conservation agriculture systems can be considered climate-smart as they deliver on the objectives of climate-smart agriculture.

Cover photo: Field worker Lain Ochoa Hernandez harvests a plot of maize grown with conservation agriculture techniques in Nuevo México, Chiapas, Mexico. (Photo: P. Lowe/CIMMYT)