Decades of on-station conservation agriculture trials reveal key farming insights for Zambia’s changing climate

Long-term research rarely offers quick fixes. More often, it is a patient pursuit, marked by seasons of uncertainty, occasional setbacks, and gradual, hard-won insights. Yet, when carefully managed, its outcomes can redefine farming systems and adaptation strategies to long-term climate trends.

This is the story of CIMMYT‘s persistence, working alongside Zambia’s Ministry of Agriculture to maintain some of Southern Africa’s most critical long-term Conservation Agriculture (CA) experiments for over two decades.

Scattered across Zambia’s contrasting agro-ecological zones, from the high rainfall Northern province to the drought-prone Southern Province, and the tropical savanna climate in the Eastern province, the Misamfu Research Station, Monze Farmer Training Centre, and Msekera Research Station have hosted these long-term trials, with Monze being established in 2005, Msekera in 2011, and Misamfu in 2016. Through searing droughts, erratic rainfall, floods, pest outbreaks and changing policy landscapes, these stations have systematically tested CA principles over multiple seasons, focusing on crop productivity, economic viability, and soil health, pest and disease dynamics, soil moisture and climate resilience among other aspects, to adapt CA to local farming conditions. More importantly, they have adapted these principles to Zambia’s diverse socio-economic realities and contexts.

Testing CA under Zambia’s climate gradients

At the core of these trials is a simple, but essential question: “Can CA systems be adapted to Zambia’s smallholder farmer conditions to improve productivity, soil health, and resilience under climate variability?”

Each research station offers a unique window into answering this question. For instance, Monze Farmer Training Centre located in Zambia’s Southern Province, hosts one of the oldest CA trials in the region. In addition, originally set up with eight main treatments and 32 trial plots, it has since expanded to 48 plots consisting of 12 treatments, testing CA under no-tillage against conventional plough-based systems with maize, cotton and sun hemp rotations of varying sequences. The plots have accumulated invaluable data, owing to the detailed and precise monitoring of yields, soil moisture, infiltration rates, pest and disease dynamics, soil quality indicators, and soil organic matter, year after year.

Christian Thierfelder, CIMMYT’s Principal Cropping Systems Agronomist and founder of all long-term experiments reflects, “When we started, CA was a hot topic in Zambia. We wanted to know its benefits if you persist with these systems under Zambia’s conditions, not just for three or five years, but over decades”.

Two decades later, key findings from these trials reveal that rotations that include cotton and/or sun hemp consistently outperform others in maize yields due to the nitrogen-fixing and soil-improving effects of the legume and deep-rooting cotton. CA plots, especially those combining minimum tillage, residue retention, and rotations, also demonstrate better soil moisture retention and infiltration, even in drought years. In fact, one striking observation has been that during intense rainfall events, water infiltration under CA plots is dramatically higher than under conventional systems, reducing flooding, erosion, and surface run-off. CA plots absorb and retain more moisture, a significant advantage as rainfall patterns become more erratic.

However, the trials have also revealed complex trade-offs that researchers alike must accommodate. For example, while the maize-cotton-sun hemp rotation delivers exceptional yields, its economic viability hinges on market dynamics. When sun hemp seed and cotton commanded reasonable prices in the past, the system was highly profitable; in its absence, farmers risk sacrificing income for soil benefits alone. Another surprising insight comes from long-term soil organic carbon (SOC) trends. While CA systems reduce erosion and improve infiltration, the anticipated build-up of SOC has remained elusive, except at one long-term trial site outside Zambia at the Chitedze Research Station in Malawi. Thierfelder notes, “Declining rainfall, declining biomass, and declining soil carbon levels are interconnected. CA alone may not reverse these trends unless combined with complementary practices like manure application or agroforestry species.”

Adapting CA for high-rainfall areas

Misamfu Research Station, in Zambia’s wetter Northern Province, has wrestled with another challenge: CA’s performance under high-rainfall conditions. Since 2016, Misamfu has hosted the long-term CA systems trial. Originally designed to conserve moisture, CA systems, especially when planted on the flat, struggle with too much moisture, leading to waterlogging, and here, not drought, is the problem. CA plots without drainage interventions have underperformed in very wet years. Yet, new innovations are emerging. Permanent raised-beds and permanent ridges, two promising CA systems developed under irrigated systems, are showing promise by improving drainage while retaining CA’s soil health benefits.

“In relatively dry years, CA systems shine,” explains Thierfelder, “but under waterlogged conditions, we now know that permanent raised beds or ridges could be the missing link.” “Over the long-term, CA systems planted on the flat are capable of buffering high rainfall effects, probably due to improved infiltration”, remarked Blessing Mhlanga, CIMMYT’s Cropping Systems Agronomist.

Capturing cumulative effects over time

Since 2011, the CA long-term experiment at Msekera Research Station in Eastern Zambia has revealed how CA performs beyond short-term seasonal gains. Unlike seasonal experiments, these trials capture the gradual, cumulative effects of CA on soil health, water use, weed and pest dynamics, and crop yields under real-world conditions. With ten treatments, including conventional tillage, ridge and furrow systems, and CA practices- such as direct seeding, residue retention, and crop rotations, the trials provide critical evidence. So far, results from Msekera show that no-tillage systems with crop residue retention, especially when combined with crop rotations, significantly improve soil moisture retention and structure, leading to more stable crop production over time.

Why long-term matters

Long-term trials are essential to fully understand the benefits and limitations of CA across a full spectrum of climate conditions. Such trials require consistent donor support, strong partnerships with research station managers, and effective field management. Unlike short-term experiments, long-term trials capture the cumulative effects of CA practices across diverse seasons, including droughts and floods.

These trials also show that CA is not a one-size-fits-all solution — its success hinges on continuous application over time. Since to date, rainfall patterns cannot be predicted precisely, deciding to adopt CA only in dry years is ineffective. Instead, long-term trials reveal how CA builds resilience and improves productivity year after year.

This body of work is more than just a collection of experiments. It is a living archive, many years of climate, crop, and soil interactions, yielding insights impossible to capture through short-term trials. “We learned, for example, that infiltration rates under CA improved noticeably within just two years,” says Thierfelder. “But understanding yield trends, soil fertility dynamics or the role of rotations takes decades.” Moreover, these trials have shown that CA is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Its benefits are context-specific, often requiring adaptive management depending on rainfall, soil type, and market conditions.

From plots to farmers’ fields

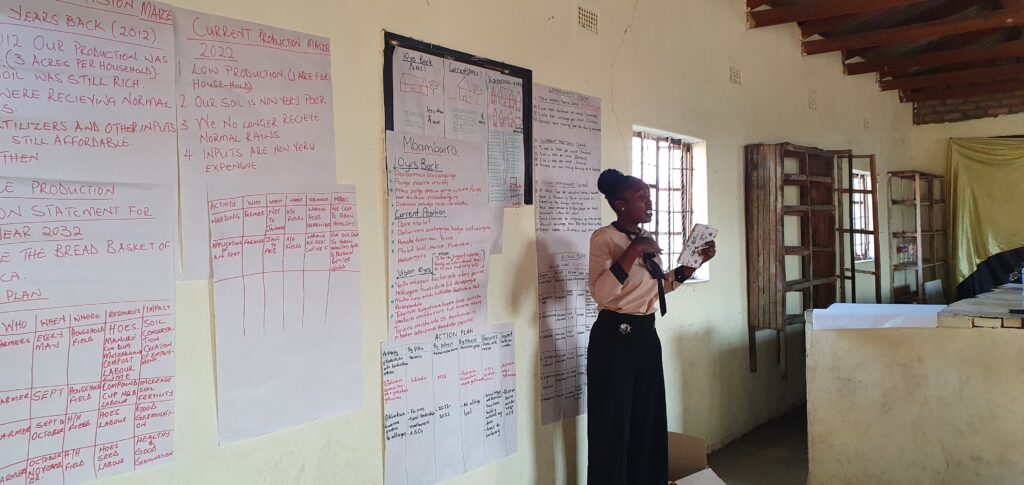

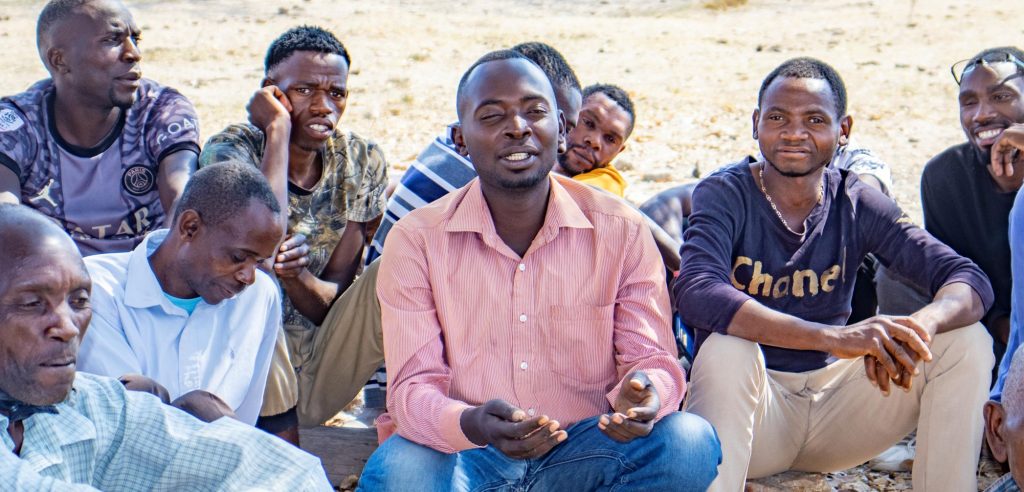

The value of this long-term work extends beyond research stations. Field days and exposure visits have allowed farmers and extension officers to engage directly with these trials, drawing lessons for their own fields. In some regions, farmers are already adapting lessons, adopting rotations, maintaining residues, experimenting with raised beds and permanent ridges, and tailoring CA to their realities. Importantly, the trials continue to evolve. While core treatments remain unchanged to preserve data integrity, small innovations, such as integrating manure or testing alternative rotations, are helping to sharpen recommendations for the next generation of CA practitioners.

The road ahead

As climate variability intensifies, the value of long-term research becomes even more critical. These trials offer answers to one of agriculture’s most urgent questions: How can CA be fine-tuned to deliver resilience and productivity? This is not just a scientific quest; it is about securing the future of Zambia’s smallholders, helping them navigate a more uncertain climate future, and ensuring their fields remain productive for the next generations.