Policy outreach to mainstream SIMLESA learning: Q&A with Paswel Marenya

The Sustainable Intensification of Maize-Legume Systems for Food Security in Eastern and Southern Africa project (SIMLESA), led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), has completed a series of country policy forums. The forums focused on maize-legume intercropping systems, Conservation Agriculture based on Sustainable Intensification (CASI) and other innovations that can help farmers in target countries shift to more sustainable farming practices resulting in better yields and incomes.

Policy makers and scientists from eastern and southern Africa will meet in Uganda at a regional forum convened by the Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa (ASARECA), 3-4 May, 2019. The forum will discuss ways to scale up the learnings of SIMLESA.

In the following interview, Paswel Marenya, CIMMYT scientist and SIMLESA leader, reflects on 8 years of project learning, what CASI means for African smallholder farmers, the dialogue between scientists and policy makers and next steps.

Q: What does sustainable intensification of the maize-legume systems mean in the African context? Why is this important for smallholder farmers?

A: Sustainable intensification is the ability to produce more food without having a negative impact on the environment and the natural resource base, but in an economically profitable, and socially and politically acceptable way. In eastern and southern Africa (ESA), maize is the most important staple and the population’s main calorie source. In Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Ethiopia annual per capita consumption of maize is around 100, 130, 70 and 50 kg respectively. This important cereal is at the center of nutrition and food security in the countries where SIMLESA has been working.

Legumes and cereals go hand-in-hand. In ESA the majority of agriculture producers – typically over 70 percent – are small farmers who farm on less than 5 hectares of land. Smallholders need sustainable diversification by intercropping maize with legumes. They get their calories from the cereals and derive proteins from the legumes. If they get marketable surplus, legumes are lucrative crops that typically fetch twice the price of maize.

Currently, the average legume yield in ESA is about 0.5 tons per hectare (t/ha). With the practices and the new varieties that SIMLESA tested, legume yield increased by 1-1.5 t/ha. Such significant yield improvement can have a huge impact on household income, food and nutritional security. For maize, the average yield in the region is about 1 t/ha, although in Ethiopia average yield is 2-2.5 t/ha. Using SIMLESA-recommended CASI practices yields of up to 3.5-4 t/ha were achieved in research-managed fields. Under farmer conditions, the yield can increase from 1-1.5 t/ha to about 2-2.5 t/ha.

SIMLESA has enabled farmers to significantly increase the productivity of maize and legumes without undermining soil health, and allowed farmers to become more resilient, especially in the face of erratic and harsh climate conditions.

Integration of small mechanization in CASI practices, particularly in Tanzania, is another positive outcome of SIMLESA. Farm labor tends to fall disproportionately on women and children in traditional systems, so the integration of machinery that can eliminate labor drudgery might alleviate the labor burden away from women.

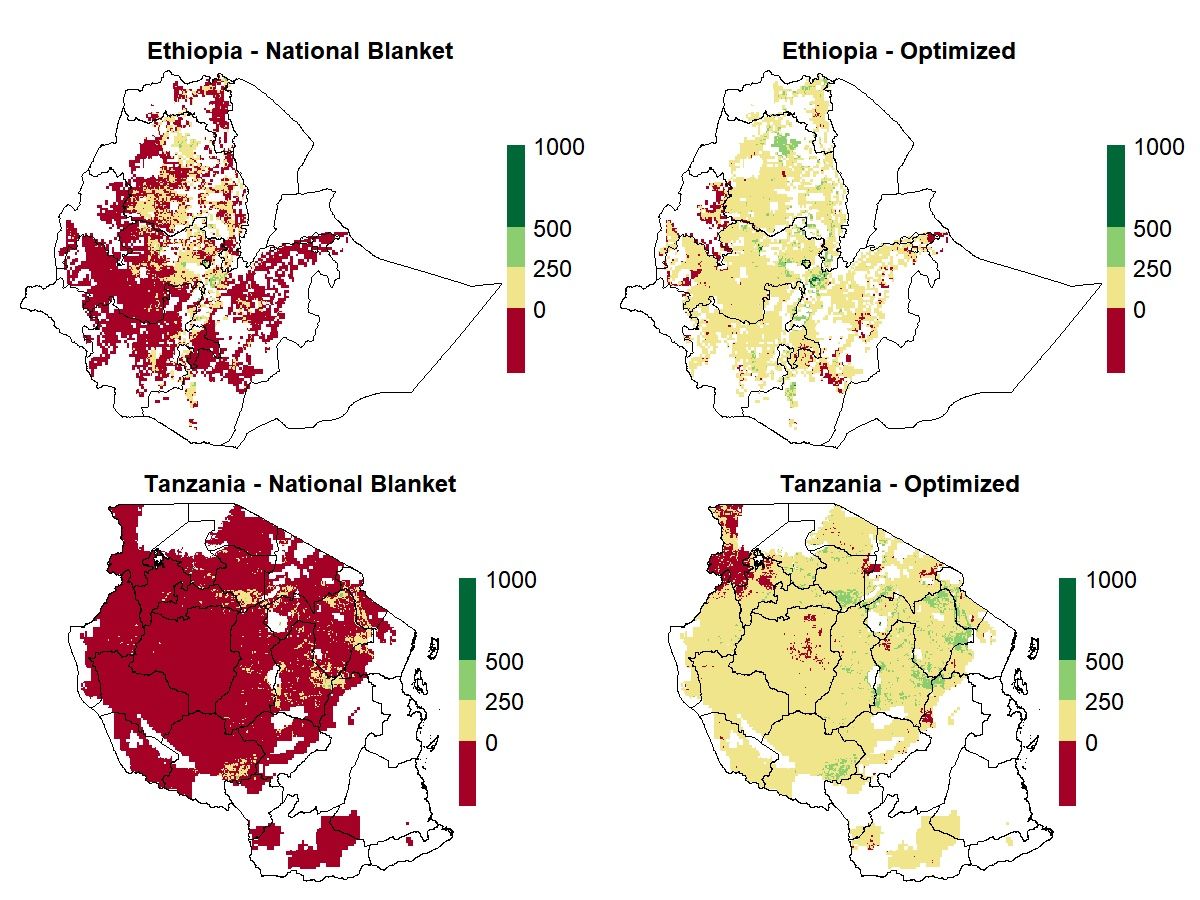

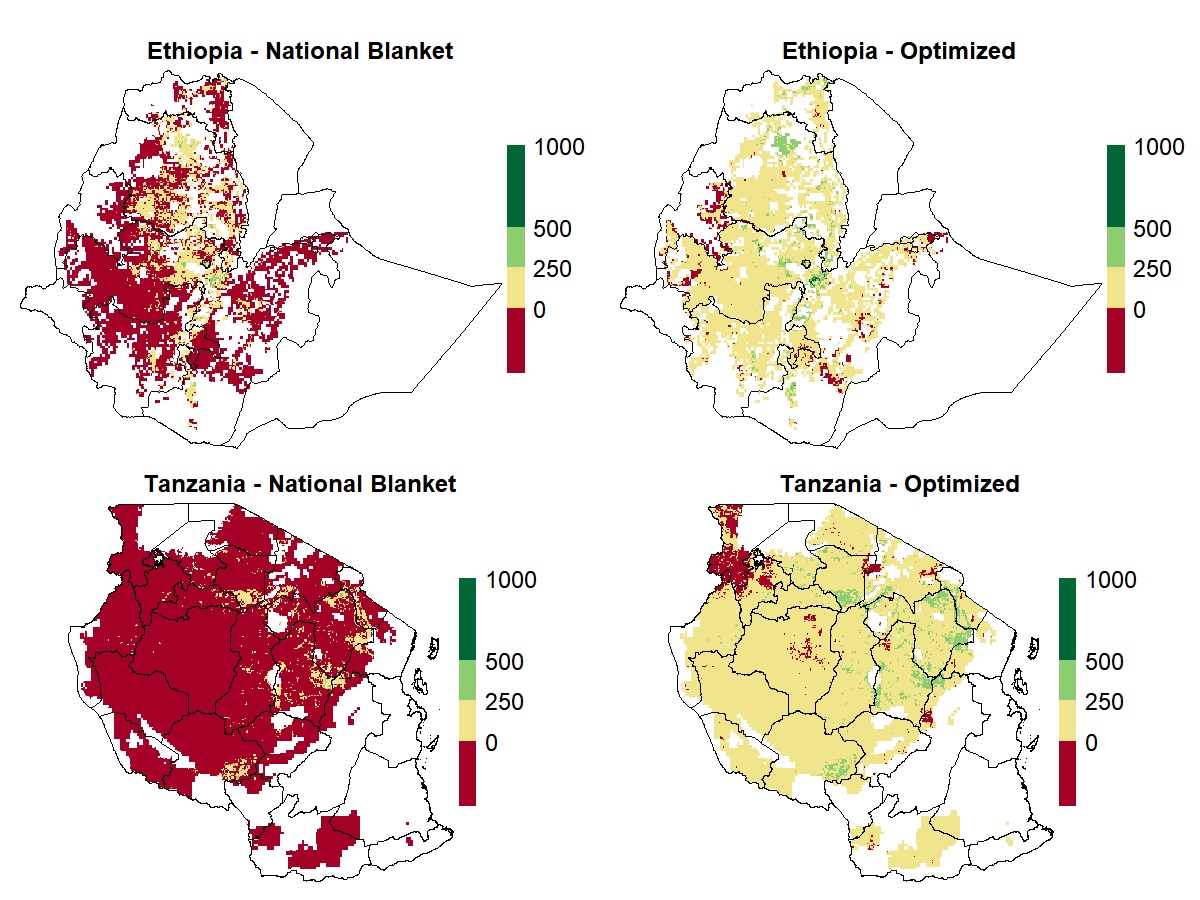

Q: How did SIMLESA identify the best approaches to improve yields and incomes in a sustainable way in each target country?

A: Africa has not experienced the green revolution that South and Southeast Asia experienced in the 1960s and 1970s, with improved varieties, irrigation and government support. Africa’s heterogenous environment calls for a different approach that is more systems oriented. The integration of disciplines from agronomy, soil science, breeding, economics and social science – including market studies and policy analysis – are part of the approach SIMLESA has used. This interdisciplinary approach is something you seldom see in many projects.

To identify best approaches, SIMLESA has conducted adaptive agronomy research, which involves scientists replicating successful experiments done in agricultural institutes or research stations in farmers’ fields under farmer resources and local conditions.

SIMLESA also promotes the notion of conservation agriculture to shift thinking in farmer practices. Conservation agriculture involves farmers growing maize and legumes in minimally tilled fields, retaining crop residue on fields without burning or discarding and implementing crop diversification.

Q: What are some of the key takeaways from the policy dialogues SIMLESA initiated in the project countries?

A: One of the things we have done in the final year of SIMLESA is policy outreach. Having done all the adaptive agronomy, socio-economic and gender studies, it is time to mainstream the results. One way of doing this is to share specific, concrete results with decision makers and explain the implication of those results to them. To do that, we organized a series of workshops in seven target countries in the region, at both the local and national levels. We shared ideas on what can be done to mainstream SIMLESA in development and research programs and in knowledge systems.

For SIMLESA practices to become the norm, more farmers need to use conservation agriculture systems, adopt improved, drought-tolerant varieties, integrate and improve legume production and where possible, practice crop rotation. At a minimum, they should do optimal and resource-conserving intercropping, conserve crop biomass for extended periods in order to recycle nutrients and organic matter and move away from aggressive tillage.

Across the seven countries, research on CASI practices should continue with proper knowledge systems put in place. Curated agronomy and socio-economic research data are easily accessible to a range of actors – scientists, farmers or agribusinesses – in a repository. Policy recommendations at country level have been summed up in a series of policy briefs.

The need to strengthen the training and mainstreaming of conservation agriculture in the curriculum at the tertiary-education level was stressed in Kenya and Tanzania. Developing the machinery value chain was recommended in Uganda, Tanzania and Mozambique. Such tools as the hoe, jab planter, riplines and the two-wheel tractor are suitable for implementing conservation agriculture practices like planting seed on untilled or minimally tilled land with crop residue. Another suggestion from Uganda, Tanzania and Mozambique was the need to focus on training of technicians who can provide machinery after-sales services and promote machinery hire to help farmers access the basic tools. Incubating businesses in custom hire services, provision of seed capital, and a focus on multi-functional mechanization also featured prominently. Another idea was to support small last-mile agribusinesses such as agro-dealers to aid scaling efforts.

Workshops also highlighted a need for government to work closely with extension services and industry associations to show the benefits of agricultural inputs on a consistent and long-term basis. This can help create markets and therefore the business case for agribusinesses to expand their distribution networks.

Q: How relevant is the issue of indigenous or local knowledge in the implementation and scale up of CASI approaches?

A: CASI principles are compatible with traditional African farming practices, especially the diversification element. African agro-ecologies are not conducive to monocropping as such, especially in areas with poor markets. If you don’t have good linkages with the markets, you will lose out, especially on the nutritional aspects. Where will you, for instance, get your proteins? African indigenous agriculture was a more self-containing system and self-regenerative in the sense that people did fallow farming, there was strong crop-livestock integration and mixed cropping systems.

Q: What are some of the adoption constraints that relate to the implementation or scale-up of CASI approaches?

A: Some of the constraints include the availability of appropriate machinery and suitable weed management. Currently, for weed management, the suggestion is to use herbicides. This is facing resistance in countries such as Kenya and Rwanda owing to the environmental effects of widespread herbicide use. The challenge is to find weed management technologies that minimize or eliminate herbicide use. The other constraint relates to markets. When you succeed in raising legume and maize production, you must find markets for them.

Another constraint concerns educating farmers on implementing the practices in the right way on a large scale. This expensive undertaking requires a public-private sector partnership. To have impact, you need large-scale farmer education and demonstrations.

Q: One of the key constraints is labor intensive activities that are inefficient and time wasting. This can be fixed with access to small mechanization. What are some of the approaches that enable smallholders’ access to farm machinery? How sustainable are these approaches?

A: This is one area that needs more work. Although machinery was not an integral part of the project design, SIMLESA scientists and national implementers found ways of assimilating machinery testing, including leveraging other CIMMYT projects such as the Farm Mechanization and Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Intensification project (FACASI), which was a SIMLESA collaborator on the farm mechanization component. Two-wheel tractors and other conservation agriculture machinery that were tested to promote the agronomy that SIMLESA was working on, especially in Tanzania, came from the FACASI project.

Q: SIMLESA stakeholders will gather at the ASARECA regional forum in early May to discuss actionable CASI programs for the public and private sector alike. What do you expect from this regional forum? If there were two or so policy recommendations to give, what would they be?

A: At the forum, we will engage with top-level officials from governments, development organizations and the private sector from ASARECA countries including Mozambique and Malawi. We expect to share the key lessons we learned from SIMLESA. The focus is on how to catalyze paradigm shifts in smallholder agronomy and accelerate institutional change that will enable the technologies to get to scale. We hope to see a communiqué, expressing the acceptance and commitment of the conclusions from the forum, developed and signed. That should serve as a lasting record of the commitments and agreements made at the forum.

Some policy recommendations include creating an enabling environment that provides nationwide CASI demonstration sites for farmers. We are encouraging the government, the private sector and community organizations to join forces and find ways of facilitating the funding for multi-year, long-term CASI demonstration and learning sites. While CASI practices are becoming mainstream in the thinking of business and government leaders, these now need to be specifically be budgeted into various agricultural programs. One key program to promote CASI is retraining extension workers to on new systems of production based on CASI principles so they can facilitate knowledge transfer and help farmers act collectively and engage with markets more effectively.