A sustainable agrifood systems approach in conflict-ridden Sudan

Sudan, the third largest country in Africa, has long been an epicenter of food production, due to its fertile lands and rich history of agricultural cultivation. But modern Sudan faces chronic food insecurity rooted in social and geopolitical challenges. A situation that has been exacerbated by the outbreak of war on April 15, 2023. The armed conflict has caused a sudden, further decline in agricultural productivity, displacing large populations and pushing millions of Sudanese into high levels of malnutrition and food insecurity.

In response to this crisis, CIMMYT, through the USAID-funded Sustainable Agrifood Systems Approach for Sudan (SASAS), is supporting agricultural development by creating robust and sustainable food production systems. SASAS adapts a modular and multi-crop approach to implement an integrated agrifood system that underpins food security, employment, and equity.

As the planting season of 2024 approaches, the project strives to strengthen food production to support the people of Sudan during these challenging times.

Experts speak: SASAS focuses on five key areas

Abdelrahman Kheir, SASAS chief of party, highlights how the agricultural innovations of the project are impacting multiple regions in Sudan. The focus of the project is on five broad intervention areas: promoting agricultural production for smallholder farmers, improving value chains and business development, supporting community management of natural resources, and providing horticultural and livestock services such as vaccination campaigns.

Further in the video, Murtada Khalid, country coordinator for Sudan, explains how the SASAS Food Security Initiative (SFSI) will provide 30,000+ farmers with a diversified package of four inputs: fertilizer, seeds, land preparation, and agricultural advisory services, to prepare for the upcoming 2024 sorghum and groundnut planting season. SFSI is a critical element of SASAS that uniquely provides agricultural development aid during a time of conflict to directly improve the food security situation in Sudan.

How women farmers benefit from SASAS

SASAS works directly with women farmers and pastoralists to ensure an equitable approach to food security in the country. Hear farmers from the women-led El-Harram Agricultural Cooperative in Kassala, Sudan, explain how SASAS has positively impacted their lives and families.

Ali Atta Allah, a farmer in Kassala expresses her gratitude for SASAS support. “They provided us with seeds including jute, mallow, okra, and sweet pepper. We planted them, and they thrived.” Ali highlighted the financial gains—a bundle of jute mallow sells for 500 Sudanese Pound (SDG). The income from the entire area amounts to 200,000 to 300,000 SDG. “The seeds provided by SASAS are of superior quality,” she affirmed.

Aziza Haroun from El-Ghadambaliya village, shares her story of how improved seeds provided by SASAS activities helped double her yields compared to previous years. “We used to farm in the same land and the yield was poor. Mercy Corps, a SASAS partner, introduced us to a new method of planting legumes as natural fertilizer. Now our yield has increased significantly,” she said.

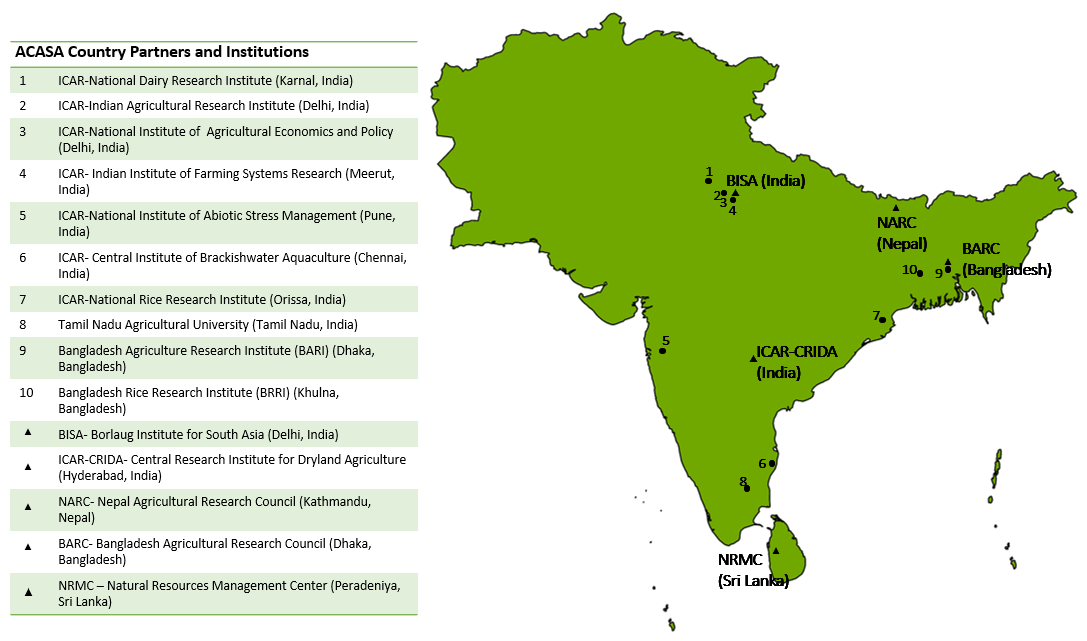

Soil is the foundation of agriculture, and healthy soil is critical to the entire ecosystem. However, soil health is under threat today as many factors make soil unhealthy, leading to significant losses in farming. CIMMYT in India has been addressing these issues in partnership with national and international institutions, while CIMMYT’s SBP program in Türkiye aims to deliver high-yielding wheat germplasm that is resistant to SBP and supports the International Soil-Borne Pathogens Research & Development Center (ISBPRDC) of Türkiye. It also facilitates knowledge exchange and technology transfer to support joint research and development activities to improve soil health.

Soil is the foundation of agriculture, and healthy soil is critical to the entire ecosystem. However, soil health is under threat today as many factors make soil unhealthy, leading to significant losses in farming. CIMMYT in India has been addressing these issues in partnership with national and international institutions, while CIMMYT’s SBP program in Türkiye aims to deliver high-yielding wheat germplasm that is resistant to SBP and supports the International Soil-Borne Pathogens Research & Development Center (ISBPRDC) of Türkiye. It also facilitates knowledge exchange and technology transfer to support joint research and development activities to improve soil health. Participants later visited winter wheat trial sites at the research station in Haymana, a district of Ankara province. The group then interacted with Mesut Keser, ICARDA’s wheat breeder who specializes in winter and facultative wheat while working on the International Winter Wheat Improvement Program (IWWIP). This was followed by a visit to the pathology field experiments, a breeder seed production area, and an experimental trial for evaluating Syngenta TYMIRIUM® technology at the research station.

Participants later visited winter wheat trial sites at the research station in Haymana, a district of Ankara province. The group then interacted with Mesut Keser, ICARDA’s wheat breeder who specializes in winter and facultative wheat while working on the International Winter Wheat Improvement Program (IWWIP). This was followed by a visit to the pathology field experiments, a breeder seed production area, and an experimental trial for evaluating Syngenta TYMIRIUM® technology at the research station. Beyhan Akin, wheat breeder at CIMMYT, gave a presentation on CIMMYT’s breeding activities in Türkiye, and Oğuz Önder presented fertilizer application on the quality of Bread Wheat and the importance of foliar fertilization in crops.

Beyhan Akin, wheat breeder at CIMMYT, gave a presentation on CIMMYT’s breeding activities in Türkiye, and Oğuz Önder presented fertilizer application on the quality of Bread Wheat and the importance of foliar fertilization in crops.