New publications: Shifting the mindset from “reaching many” to sustainable change

Over the last few years, the research and development communities have deemed “scaling” a priority in order to help contribute to and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). On smaller scales, there has been great success in reducing hunger and poverty, but it has rarely expanded to regional or national levels.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) scaling head Lennart Woltering, in collaboration with colleagues Kate Fehlenberg and Bruno Gerard, as well as with international development experts Jan Ubels of SNV and Larry Cooley of Management Systems International, have been studying the process of scaling to understand why successful pilot projects are no guarantee for success at scale.

In a new paper published in Agricultural Systems, they argue that pilot projects are usually set up and managed in heavily controlled environments that do not reflect the reality at scale. Furthermore, confusion of what scaling is and how it can be executed often results in a narrow focus on solely reaching numbers.

“Counting household adoption of a practice at the end of a project is a poor metric of whether these people can and will sustain adoption after the project ends, let alone if adoption will reach others and actually contributes to improved livelihoods,” Woltering states.

According to Woltering, “This paper is a call for a new scaling narrative, from one that is short-term and piecemeal, to one that recognizes the systemic nature of problems and solutions to achieve sustainable change at scale.”

This requires a change in mindset, skills and ways of collaborating than what we currently consider normal. “Meaningful impact at scale hardly occurs within a project context, but when new ways of working are becoming ‘the new normal’ by a critical mass of actors ‘in the real world’,” Woltering explained.

The authors present a number of frameworks that help to assess the scalability of innovations and the design of scaling strategies from the onset of projects and how to systematically think through key elements needed for scaling success. This includes CIMMYT’s very own Scaling Scan. Reaching the SDGs requires scaling interventions to be seen as building blocks within a system of other initiatives with the same goals.

Read the full study:

Scaling – from “reaching many” to sustainable systems change at scale: A critical shift in mindset

Read more recent publications by CIMMYT researchers:

- A rapid monitoring of NDVI across the wheat growth cycle for grain yield prediction using a multi-spectral UAV platform. 2019. Hassan, M.A., Mengjiao Yang, Rasheed, A., Guijun Yang, Reynolds, M.P., Xianchun Xia, Yonggui Xiao, He Zhonghu. In: Plant Science v. 282, p. 95-103.

- Characterization of TaCOMT genes associated with stem lignin content in common wheat and development of a gene-specific marker. 2019. Luping Fu, Yonggui Xiao, Yan Jun, Jindong Liu, Weie Wen, Yong Zhang, Xia Xian-Chun, He Zhonghu. In: Journal of Intregative Agriculture v. 18, no. 5, p. 939-947.

- Dissecting conserved cis-regulatory modules of Glu-1 promoters which confer the highly active endosperm-specific expression via stable wheat transformation. 2019. Jihu Li, Ke Wang, Genying Li, Yulian Li, Yong Zhang, Zhiyong Liu, Xingguo Ye, Xianchun Xia, He Zhonghu, Shuanghe Cao. In: The Crop Journal v. 2, no.1, p. 8-18.

- Effects of bran hydration and autoclaving on processing quality of Chinese steamed bread and noodles produced from whole grain wheat flour. 2019. Zhang Yan, Fengmei Gao, He Zhonghu. In: Cereal Chemistry v. 96, no. 1, p. 104-114.

- Occurrence and seasonal variation of the root lesion nematode Pratylenchus neglectus on cereals in Bolu, Turkey. 2019. Dababat, A.A., Senol Yildiz, Duman, N., Ciftci, V., Imren, M. In: Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry v. 43, p. 21-27.

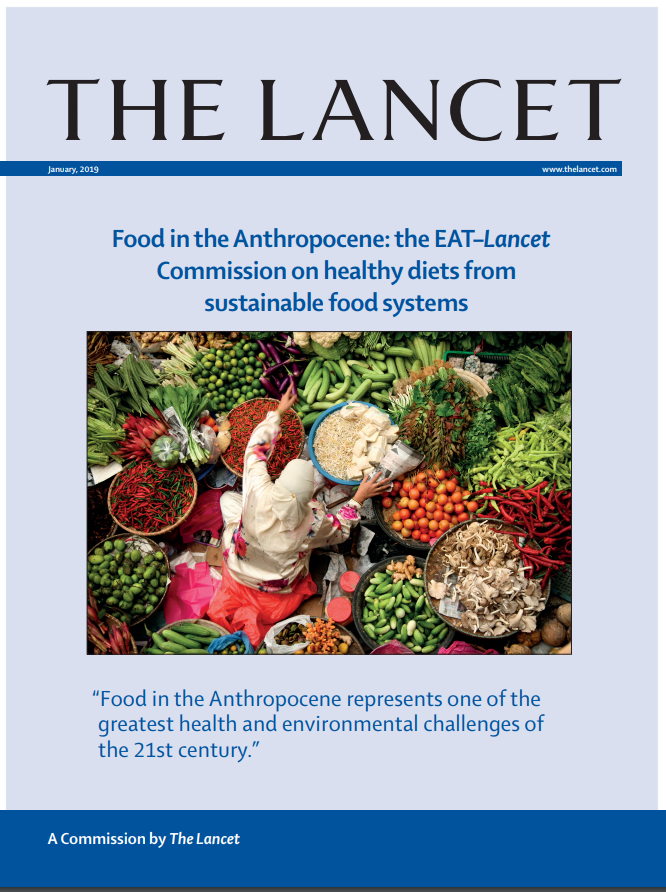

A new report by more than 30 world-leading experts in health and environmental sustainability offers a roadmap for a global food system that provides a healthy, sustainable diet for the world’s 10 billion people by 2050.

A new report by more than 30 world-leading experts in health and environmental sustainability offers a roadmap for a global food system that provides a healthy, sustainable diet for the world’s 10 billion people by 2050.

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Through pure coincidence, Susanne Dreisigacker fell into the world of agricultural science and landed in Mexico. Her interest in genetics and biology solidified when she arrived at the

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) — Through pure coincidence, Susanne Dreisigacker fell into the world of agricultural science and landed in Mexico. Her interest in genetics and biology solidified when she arrived at the